48 Interesting Pics That Show The Side Of History That Didn’t Make The Cut Into Textbooks (New Pics)

The world is constantly changing, and eventually, our memory alone isn't enough to portray how things really were. It can distort important details, leaving gaps in our understanding of the past. That’s why archives are so valuable.

The Facebook group Old Historical Photos is home to hundreds of images from days gone by. Thanks to the community's dedication to record keeping, we get to see the events, places, and people that might otherwise be lost to time. Previous eras feel much more tangible.

This post may include affiliate links.

Kids playing in the mud, 1960s Glasgow.

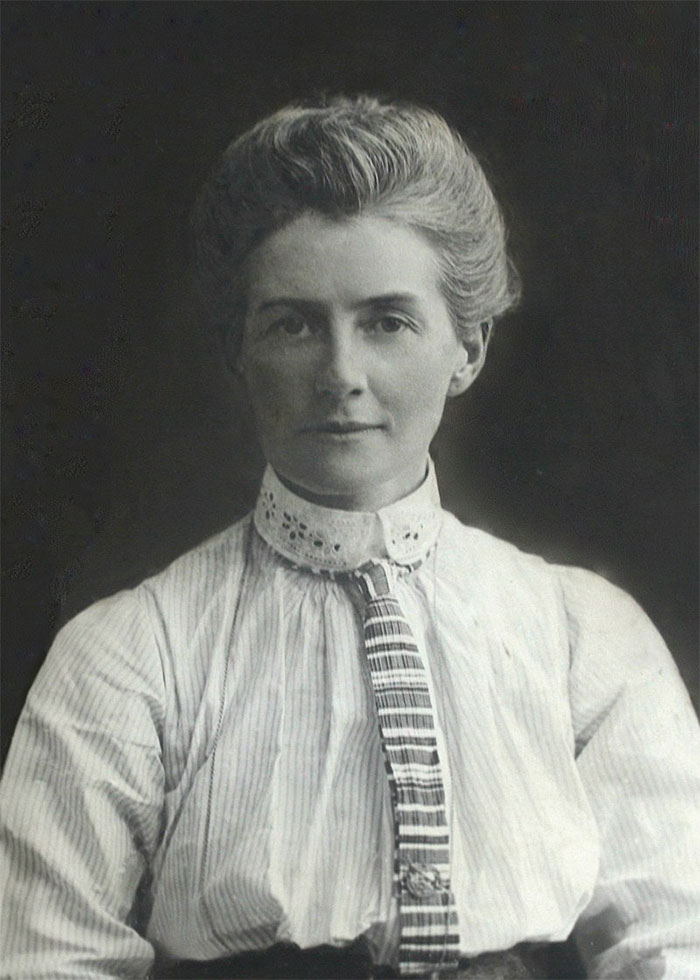

“Patriotism is not enough”: The Nurse Who Defied an Empire Edith Cavell was not just a nurse—she was a beacon of moral courage in one of history’s darkest hours. Born in 1865 in Norfolk, England, she revolutionized nursing education in Belgium and served as matron of a Brussels training hospital. When World War I erupted and German forces occupied Belgium, Cavell chose to stay behind, continuing to treat all wounded soldiers—Allied or German—with equal care. But her compassion didn’t end at the hospital doors. Quietly, she joined a resistance network that helped some 200 Allied troops escape to the safety of the Netherlands.

Her actions eventually drew the attention of German authorities. Arrested in August 1915, Cavell stood trial in a military court and was sentenced despite international protests. She delivered her now-famous final words: “Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

The German battlecruiser Prinz Regent Luitpold being towed back to Rosyth, flipped keel-up.

The ship was among numerous vessels scuttled by their crews at Scapa Flow on June 21, 1919, following the surrender of the German fleet in November 1918.

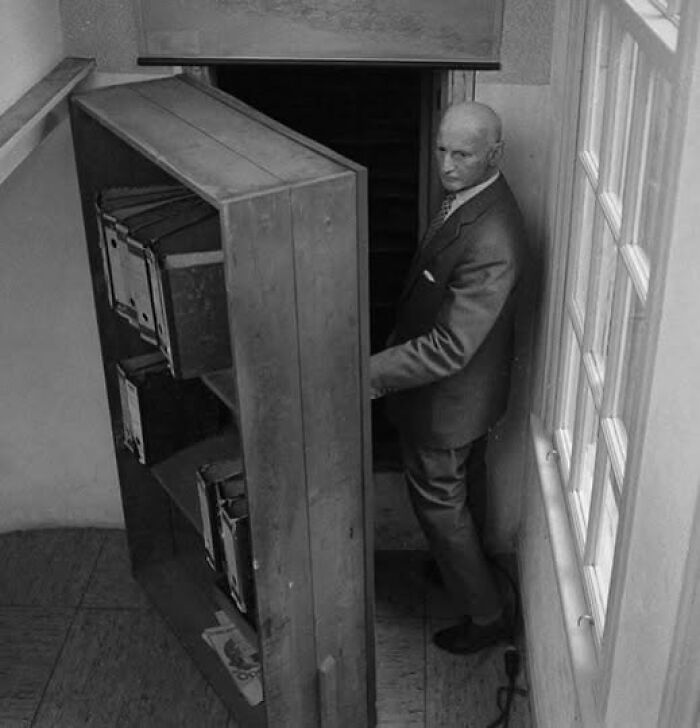

Anne Frank’s father Otto revisits the attic entrance where he and his family hid for two years before their betrayal. Amsterdam. 1960.

In March 1946, a German soldier returned to his home in Frankfurt after World War II. When he arrived, he found his house had been destroyed, and his family was no longer there.

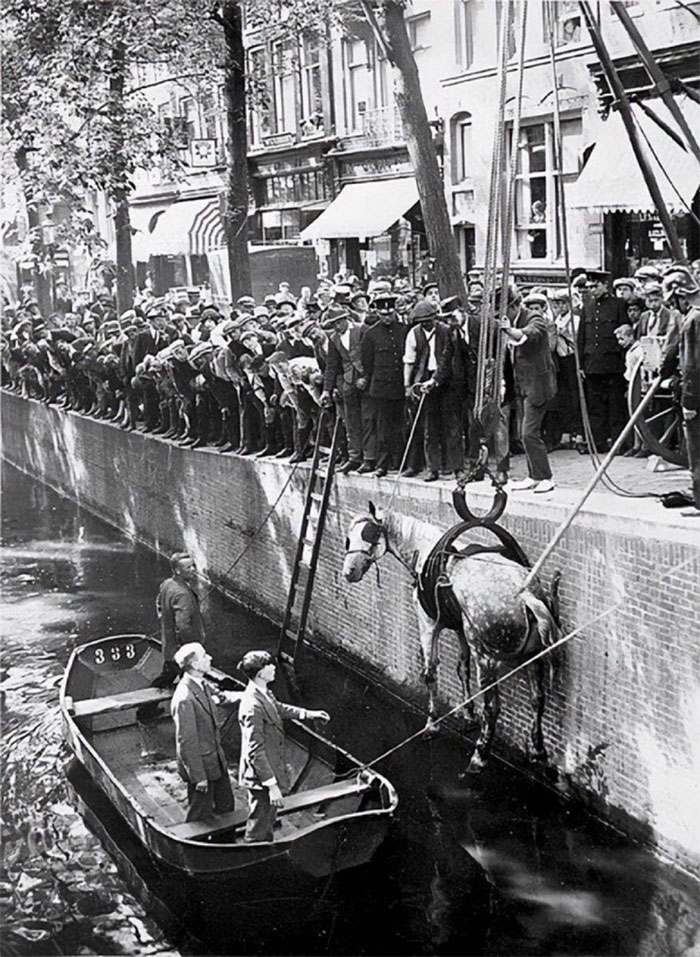

Rescuing a Horse That Fell in the Canal, Amsterdam, 1929

A Forgotten Moment of Compassion in a Changing City

In the cold spring of 1929, amid the cobbled streets and rhythmic bustle of interwar Amsterdam, a photograph was taken that, for decades, remained tucked away in dusty municipal archives. It showed a moment frozen in time: a horse, half-submerged in the frigid waters of one of Amsterdam’s countless canals, its eyes wide with fear, steam rising from its drenched coat into the morning air. Around it, a group of men—dock workers, police officers, and passing civilians—fought against time, gravity, and the elements in a desperate attempt to pull the distressed animal from the water.

The rescue, while seemingly a modest episode in the broader sweep of history, captured something rare and telling about the human spirit in an age of transformation. This black-and-white image, labeled simply “Rescuing a horse from the canal, Amsterdam, 1929”, offers a glimpse into a vanishing world—one in which working animals were not only vital to city life but also deeply interwoven into the rhythms and responsibilities of human society.

At the time, Amsterdam was a city straddling two centuries: modern trams rattled alongside horse-drawn carts, and steel bridges arched over ancient waterways still patrolled by wooden barges. Though the automobile had begun to assert itself, the horse remained essential to transport and trade, particularly in older neighborhoods where narrow lanes and canal-side warehouses made mechanized traffic impractical. The horse in question, later identified in city records as “Gerda,” belonged to a local milk deliveryman. Every morning, she pulled a heavy cart through the Jordaan district, her iron shoes clinking softly on the slick stones, her breath visible in the crisp dawn air.

On that particular morning, something went wrong. Accounts from the time suggest that Gerda was startled—perhaps by the screech of a passing tram or the bark of a stray dog. In a moment of panic, she veered from the path and crashed through a weak wooden guardrail, plunging into the dark canal below. The sound of the splash echoed through the neighborhood, drawing a crowd within moments.

What followed was a chaotic but moving display of communal effort. The photograph—snapped by Willem de Jong, an amateur photographer and postal worker—captures the peak of the drama. A thick rope is looped around Gerda’s chest; two men in flat caps grip it with white-knuckled intensity, leaning backward in tandem. Another man balances on the edge of the canal, holding the horse’s bridle and murmuring softly, trying to calm the shivering animal. In the background, onlookers line the bridge, their faces a mixture of concern, awe, and quiet determination.

According to the municipal reports and de Jong’s own journal, the rescue took over an hour. A pulley system, borrowed hastily from a nearby construction site, was rigged to a wagon axle. With combined human effort, the horse was hoisted, inch by agonizing inch, up from the water’s grasp. Children who had gathered in their school uniforms cheered as Gerda finally collapsed onto the street, her flanks heaving, soaked but alive. A local woman brought warm blankets; a café owner offered buckets of hot mash and water. The milkman, tears in his eyes, knelt beside his companion, stroking her nose in disbelief.

News of the incident made it into local papers the next day. The Amsterdamsche Courant ran a small column titled “Horse Rescued from Canal—Citizens Act Heroically,” praising the cooperation between ordinary citizens and police. Though the story occupied only a few inches of print, it resonated deeply with a public anxious about change. In a time when machines were rapidly replacing animals and people alike, Gerda’s rescue served as a gentle reminder of shared responsibility and empathy.

As years passed and the horse-drawn cart gave way to motor vehicles, such scenes became increasingly rare. Horses slowly disappeared from the city streets, their memory preserved only in photographs, paintings, and the faint outlines left on old cobblestones. The photograph itself, once relegated to a cardboard file in the city archives, was rediscovered in the 1980s during a retrospective on Amsterdam’s urban evolution. Since then, it has been featured in exhibitions on early 20th-century life, animal welfare, and historic acts of civic unity.

To modern eyes, the image of Gerda's rescue might appear quaint—an artifact from a simpler time. But beneath its surface lies something timeless: the universal instinct to help, to care, and to preserve life, no matter how ordinary or immense the challenge. It reminds us that history is not just shaped by wars, politics, and revolutions, but also by small, human gestures—a rope thrown, a hand extended, a life saved.

The canal still flows where the rescue occurred, bordered now by bicycles and modern signage. Few who pass the spot know what happened there nearly a century ago. But in a framed print hanging quietly in the Amsterdam City Archives, Gerda’s story endures—her wide eyes and flaring nostrils a testament to both fear and survival, and to the people who, for one morning, made a difference.

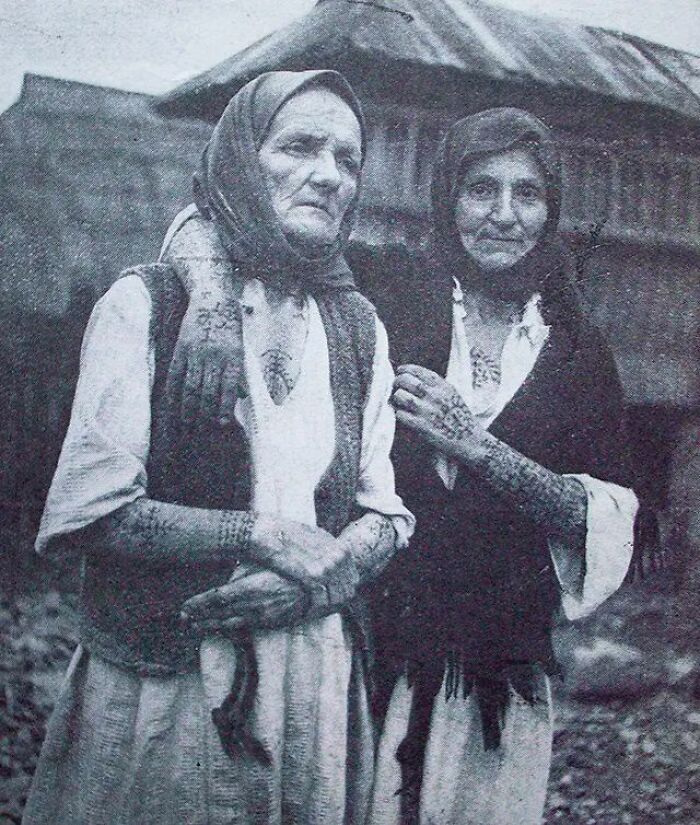

Elderly women with tattoos characteristic of Croatian Catholics in Bosnia. Central Bosnia, late 1930s.

Wow. My grandmother's family was Slovenian and very Catholic and I have never heard of this. Fascinating.

U-118, a World War I German Submarine Washed Ashore on the Beach at Hastings, England, 1919 In one of the most extraordinary and visually striking events of the post–World War I period, the German submarine U-118, a large and formidable U-boat of the Imperial German Navy, became an unexpected and dramatic feature on the shores of southern England. In April 1919, during the tumultuous period following the end of the First World War, the vessel broke loose while being towed to France for scrapping and was driven ashore by violent weather. The immense steel hulk of U-118 came to rest on the beach directly in front of the Queen's Hotel in Hastings, East Sussex. This unplanned beaching instantly transformed a quiet seaside town into a national sensation. Towering above the beachgoers and silhouetted against the coastal skyline, the 267-foot-long submarine captured the imaginations of thousands. For weeks, if not months, the wreck attracted vast crowds—locals and tourists alike—who traveled to witness this surreal spectacle of war stranded amid the peacetime sands. The grounded U-boat provided an eerie and tangible symbol of the conflict that had only recently ended—a towering machine of war brought low and rendered harmless, now a curiosity to be examined up close. Photographers documented the scene extensively, producing a wealth of historic photographs that captured both the scale of the submarine and the public's fascination. Children clambered around its barnacled hull, while men in bowler hats and women in Edwardian dress posed for snapshots. The British authorities even briefly allowed guided tours inside the vessel, though these were halted after two coast guards involved in the inspections reportedly [passed away] from toxic fumes released by the decaying submarine’s batteries. Eventually, the submarine was dismantled and removed, but the images live on in archives and personal collections. The sight of U-118 embedded in the English coastline remains one of the most remarkable visual records of the immediate postwar period. It serves as a potent reminder of the reach of the First World War and the strange, sometimes surreal ways its aftermath continued to echo across Europe long after the guns had fallen silent.

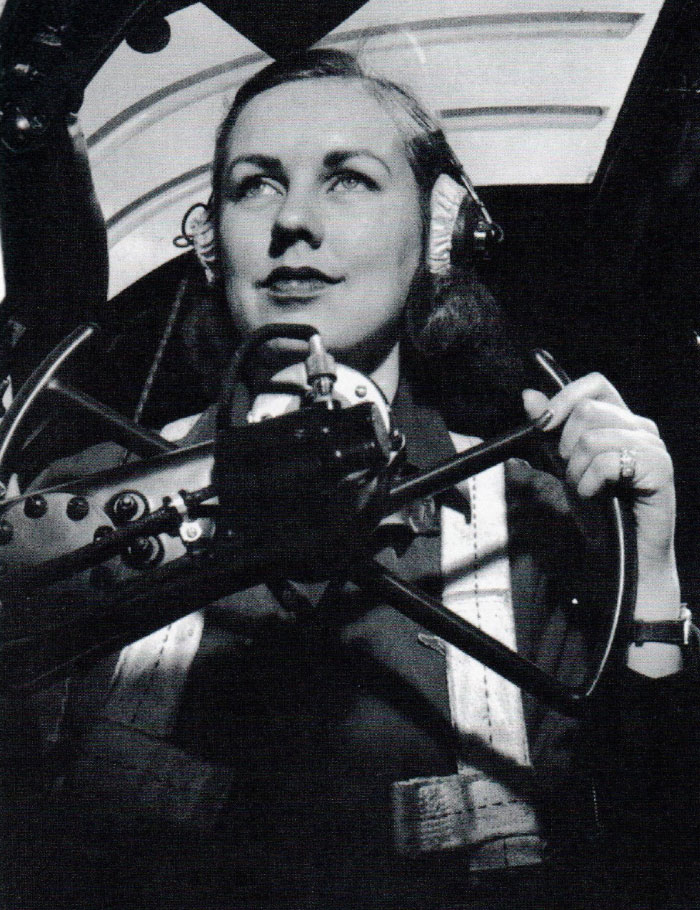

Shirley Slade was a pilot in the Women Airforce Service Pilots program during World War II. During her time in service, Shirley was stationed at three different bases, and primarily flew Bell P-39 Airacobras and Martin B-26 Marauders, two notoriously difficult aircraft to fly. In july 1943 she was featured on the cover of LIFE magazine. Shirley passed away on April 26, 2000.

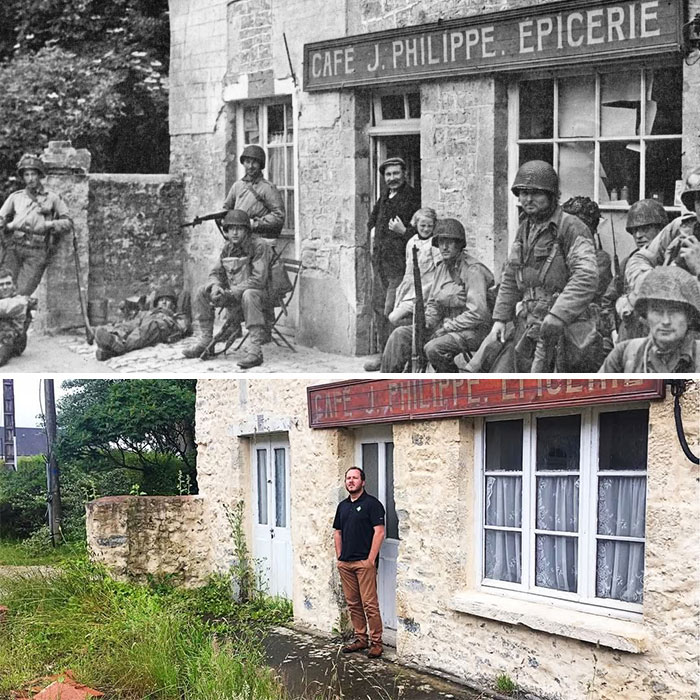

"From Liberation to Legacy: St-Mère-Église Then and Now" In the summer of 1944, the small French town of Sainte-Mère-Église etched its name into history as one of the first to be liberated during the D-Day invasion. Nestled in Normandy, this quiet village was thrust into the global spotlight on the night of June 5–6, when American paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division dropped from the skies under fire, landing amid chaos, smoke, and confusion. By dawn, the stars and stripes waved over the town square, and a new chapter in the fight against tyranny had begun. Just hours after fierce combat, scenes of camaraderie emerged—U.S. infantrymen resting, smiling, and sharing drinks with the grateful locals they had just freed. These powerful images from 1944 show more than just military victory—they reveal human connection. War-weary GIs, some barely out of their teens, found comfort in the hospitality of villagers who had endured years of occupation. Bottles of wine and cider were passed around, hands shaken, and laughter returned to streets that had echoed with fear only a day before. The bond formed in Sainte-Mère-Église became symbolic of the deep gratitude between France and the United States, forged in the blood and bravery of shared sacrifice. Fast forward to today, and that spirit is still alive. The town remains a living memorial, with parachutes still hanging from church steeples and veterans honored like family. Each year during D-Day commemorations, Sainte-Mère-Église fills with visitors, reenactors, and descendants of those who fought, walking the same cobblestone streets where history unfolded. The contrast between the black-and-white images of 1944 and the colorful, peaceful town of today is striking—but the soul of the place, shaped by freedom and remembrance, remains untouched. St-Mère-Église is more than a point on a map—it’s a testament to resilience, gratitude, and the enduring power of liberation. From the muddy boots of tired soldiers to the smiles shared with liberated villagers, this town reminds us that history lives not just in textbooks, but in moments of hope, humanity, and hard-won peace.

A young woman in her kitchen in Jefferson, Texas, 1939.

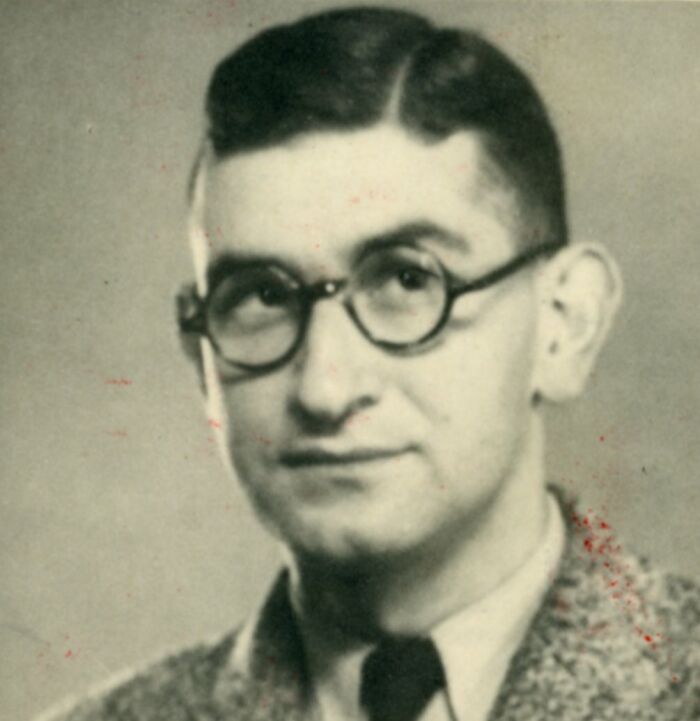

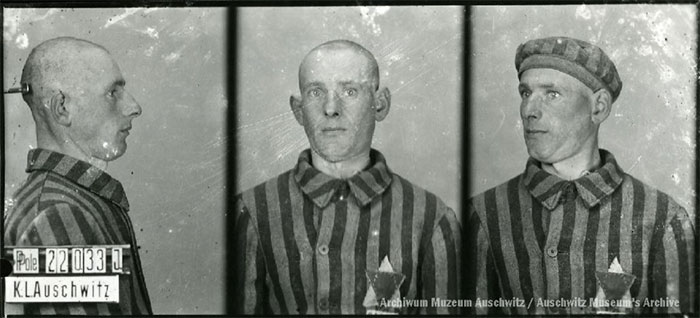

April 30, 1910 | Josef Frank, a Czech Jew, was born in Prostějov.

On September 28, 1944, he was deported from the Theresienstadt ghetto to Auschwitz, where he perished.

Jane Kendeigh: The Courageous Flight Nurse Who Made History

On March 4, 1945, Jane Kendeigh made history when she became the first flight nurse to land on an active battlefield. Her plane touched down on the tiny, war-torn island of Iwo Jima, where American forces were locked in a fierce and deadly battle during World War II. Her mission was both daring and compassionate—to bring comfort and care to the wounded and help evacuate them to safety.

"Wait for Me Daddy" by Claude P. Dettloff, October 1, 1940.

“Wait for Me, Daddy” is an iconic photo taken by Claude P. Dettloff on October 1, 1940, of The British Columbia Regiment (Duke of Connaught’s Own Rifles) marching down Eighth Street at the Columbia Street intersection, New Westminster, Canada. Link follows.

Devil's Tower in Wyoming is not just a geological wonder; it's a jaw-dropping spectacle that challenges our understanding of reality itself. Some wild imaginations take it a step further, claiming it's the remnant of an ancient giant tree trunk. This striking formation became even more legendary when it was showcased as a crucial landmark in Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," setting the stage for an electrifying career launch.

wild imaginations = conspiracy theories * (as far as we know today ..... 😏)

"Woven with Power: The Tlingit Chilkat Coat of Prestige and Spirit"

Crafted in the late 19th century, this Tlingit Chilkat coat—dated to around 1885 CE—is far more than a garment. It is a living tapestry of Indigenous tradition, identity, and prestige, woven with techniques passed down through generations. Now preserved at the Portland Art Museum, this extraordinary robe is a product of Tlingit artistry and cultural expression, made from mountain goat wool, otter fur, and strips of cedar bark—materials as deeply rooted in the land as the people who fashioned them.

The Chilkat robe is among the most sacred and intricate textiles of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Named after the Chilkat Tlingit people of Alaska, these robes were traditionally worn by high-ranking clan leaders during dances and ceremonies, each design imbued with clan crests, ancestral spirits, and cosmological symbols. The complex abstract forms, known as formline design, depict animals and mythical beings, each shape flowing into the next with striking symmetry. The weaving technique is so time-consuming and skillful that a single robe could take a year or more to complete.

More than ceremonial regalia, Chilkat robes functioned as emblems of status, lineage, and power. The materials themselves carry meaning—mountain goat wool symbolizes the harsh alpine spirit world, cedar bark embodies protection and purification, and otter fur, soft and sleek, adds both elegance and practicality. These robes were not simply worn; they were inherited, danced, and revered, often wrapped around chiefs during speeches to invoke ancestral authority or presented as treasured gifts during potlatch ceremonies.

Today, as this piece rests in a museum far from its coastal homeland, it serves not only as a masterpiece of textile art but also as a reminder of the resilience and richness of Indigenous cultures. It invites us to reflect on the Tlingit worldview, where every thread is a story, every symbol a spirit, and every garment a bridge between past and present.

Macedonian villagers in traditional costumes.

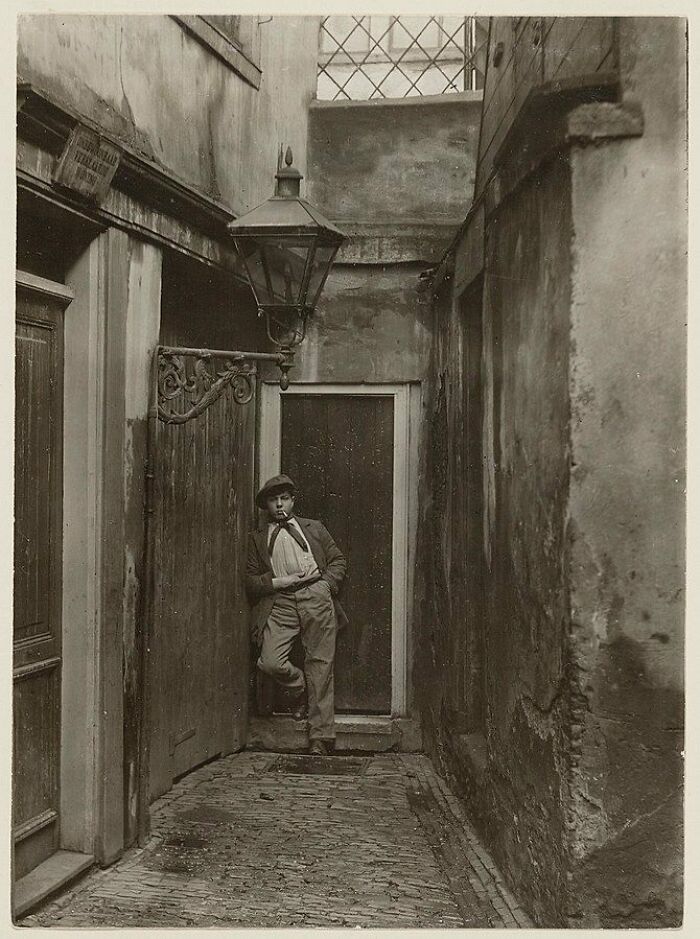

A man photographed in Bethelemsgang, Amsterdam, Netherlands, in 1911. The image was captured by August F.W. Vogt.

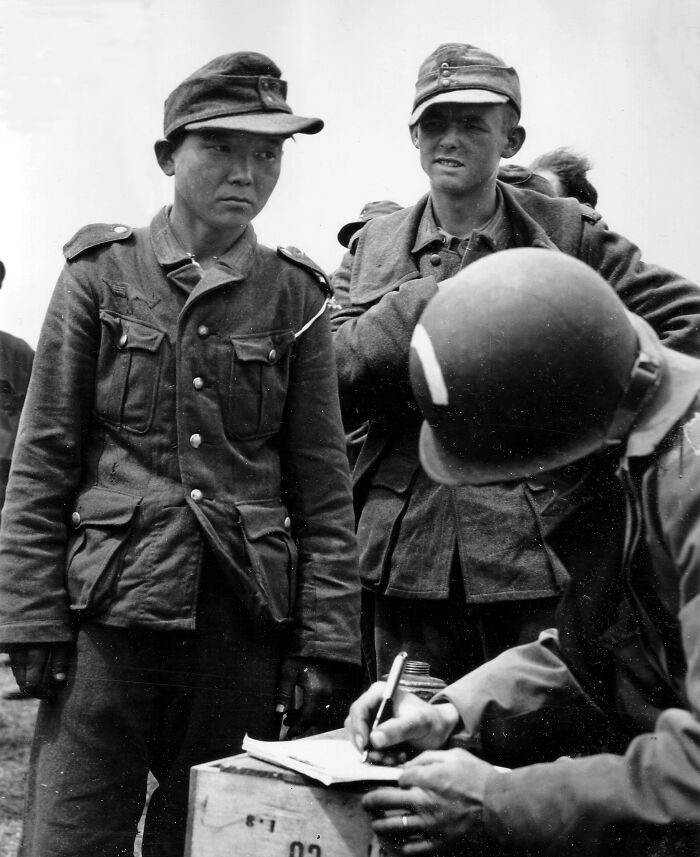

From Korea to Normandy: The Soldier Who Wore Three Uniforms

On June 7, 1944—just one day after D-Day—a soldier from the U.S. 5th Engineer Special Brigade, identifiable by the white bow on his helmet, was registering newly captured Wehrmacht prisoners on Utah Beach, Normandy. Among them was a man with a story stranger than fiction: Yang Jong-Kyoung Shin Euijoo, born in Korea on March 3, 1920. His journey to this moment had spanned continents, empires, and three different armies.

Shin’s odyssey began in 1938 when, under Japanese colonial rule in Korea, he was conscripted into the Japanese Kwantung Army. He was later captured by Soviet forces during the Battle of Khalkhin Gol (Nomohan), a fierce border conflict between Japan and the USSR. Like many captured soldiers, he was sent to a labor camp—only to be later pressed into service again, this time in a Soviet uniform.

Fate twisted yet again in 1943, when Shin was captured by German forces during the brutal fighting around Kharkov on the Eastern Front. The Germans, short on manpower, conscripted some prisoners into the Wehrmacht. Thus, by the time of his final capture by American forces in Normandy, Shin had worn the uniforms of three powerful—and opposing—militaries.

His story, though rare, is a testament to the complex, often coercive nature of war and empire in the 20th century. Shin represents thousands of conscripts swept up by global conflict, powerless to choose their allegiance. That a Korean man could end up a German prisoner on a French beach—after serving in Japanese and Soviet forces—shows just how far World War II reached into every corner of the world.

Helen Mirren once said: Before you argue with someone, ask yourself, is that person even mentally mature enough to grasp the concept of a different perspective. Because if not, there's absolutely no point. Not every argument is worth your energy. Sometimes, no matter how clearly you express yourself, the other person isn’t listening to understand—they’re listening to react.

They’re stuck in their own perspective, unwilling to consider another viewpoint, and engaging with them only drains you.

There’s a difference between a healthy discussion and a pointless debate. A conversation with someone who is open-minded, who values growth and understanding, can be enlightening—even if you don’t agree. But trying to reason with someone who refuses to see beyond their own beliefs? That’s like talking to a wall. No matter how much logic or truth you present, they will twist, deflect, or dismiss your words, not because you’re wrong, but because they’re unwilling to see another side.

Maturity isn’t about who wins an argument—it’s about knowing when an argument isn’t worth having. It’s realizing that your peace is more valuable than proving a point to someone who has already decided they won’t change their mind. Not every battle needs to be fought. Not every person deserves your explanation.

Sometimes, the strongest thing you can do is walk away—not because you have nothing to say, but because you recognize that some people aren’t ready to listen. And that’s not your burden to carry.

Let's take a moment to appreciate the audacity of fashion from the 15th to 17th centuries—the chopines. These towering shoes were not just an accessory; they were a bold statement, reserved for the elite women of Venice, from noblewomen to courtesans. Crafted with sky-high wooden platforms, chopines were designed to keep those luxurious dresses pristine, sparing them from the muck and grime of the streets. Talk about style with a purpose! More than mere footwear, they were the ultimate status symbol, elevating the wearer both physically and socially, a testament to their wealth and elegance. It’s fascinating, isn’t it, how today’s fashion continues to draw from this audacious history.

Officer friendly dumping out Beer rather than arresting minors for drinking 1972

In 1972, somewhere in small-town America, a police officer chose compassion over cuffs. Dubbed "Officer Friendly" by locals, he encountered a group of underage teens caught drinking. But instead of making arrests, he gave them a warning—and poured the beer out on the pavement.

It was a moment that reflected a shifting attitude in parts of law enforcement during the early '70s: less zero-tolerance, more community-minded. While not every officer would have handled it this way, scenes like this helped build trust between youth and police, showing that sometimes, a little discretion can go a long way.

There's no crime in drinking beer, here in the UK - well, with certain exceptions (particular places can have orders imposed banning public drinking, things like that). There are laws against buying and supplying alcohol to underage persons, but that's about it. America, land of the free? 🤨🤣

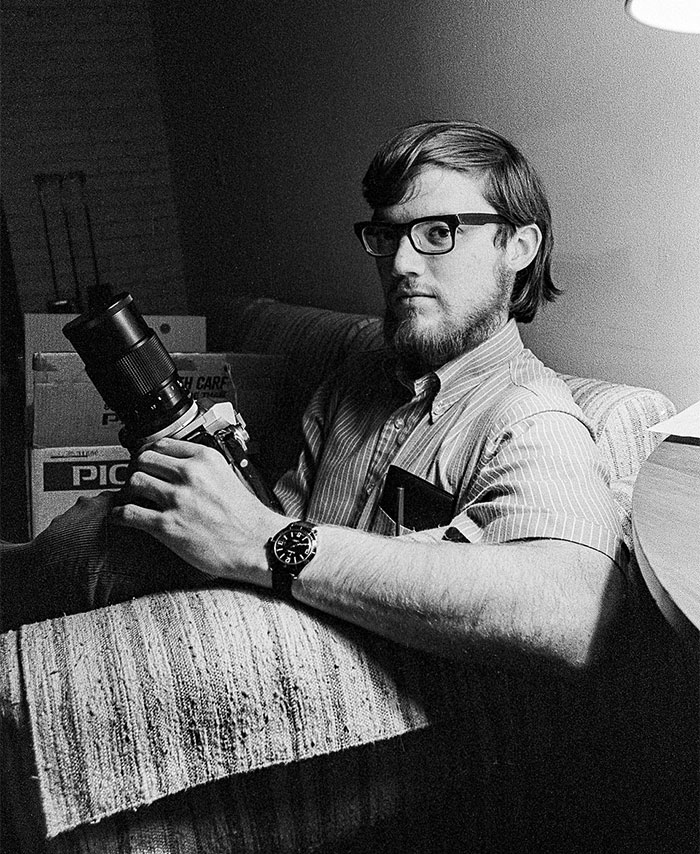

"Through the Lens of Tragedy: Remembering Reid Blackburn and the Eruption of Mount St. Helens" On May 18th, 1980, a violent act of nature silenced the eye of a young storyteller.

Reid Blackburn, a talented National Geographic photographer, was just 27 years old when he lost his life in the catastrophic eruption of Mount St. Helens. Sent to document the rumblings of the restless mountain, Reid was stationed only 13 kilometers away when the volcano unleashed one of the most devastating natural disasters in U.S. history. A pyroclastic flow—an unstoppable surge of superheated gas and ash—swept through the area, reshaping the landscape in moments.

Reid had been covering the increasing seismic activity for National Geographic, The Columbian newspaper, and the U.S. Geological Survey. Known for his creativity, calm demeanor, and sharp visual instincts, Reid was not a thrill-seeker chasing danger—he was a quiet observer, trying to capture history as it unfolded. He camped near the mountain’s slopes, not knowing that the eruption would come with such unexpected force and fury. The lateral blast, triggered by a massive landslide, ejected debris and gases at hundreds of miles per hour—obliterating everything in its path. In the days after the disaster, Blackburn’s camera and car were found buried beneath ash, and though he did not survive, his final assignment left behind a powerful legacy.

His photos taken before the eruption remain some of the most haunting and beautiful glimpses into the moments leading up to nature’s fury. He [passed away] doing what he loved—documenting the fragile dance between Earth’s majesty and its unpredictability. We honor Reid Blackburn not just as a casualty of Mount St. Helens, but as a brave chronicler who gave his life in pursuit of truth and understanding. His story reminds us of the risks borne by journalists and photographers who stand on the edge of danger so the rest of us can see the world more clearly.

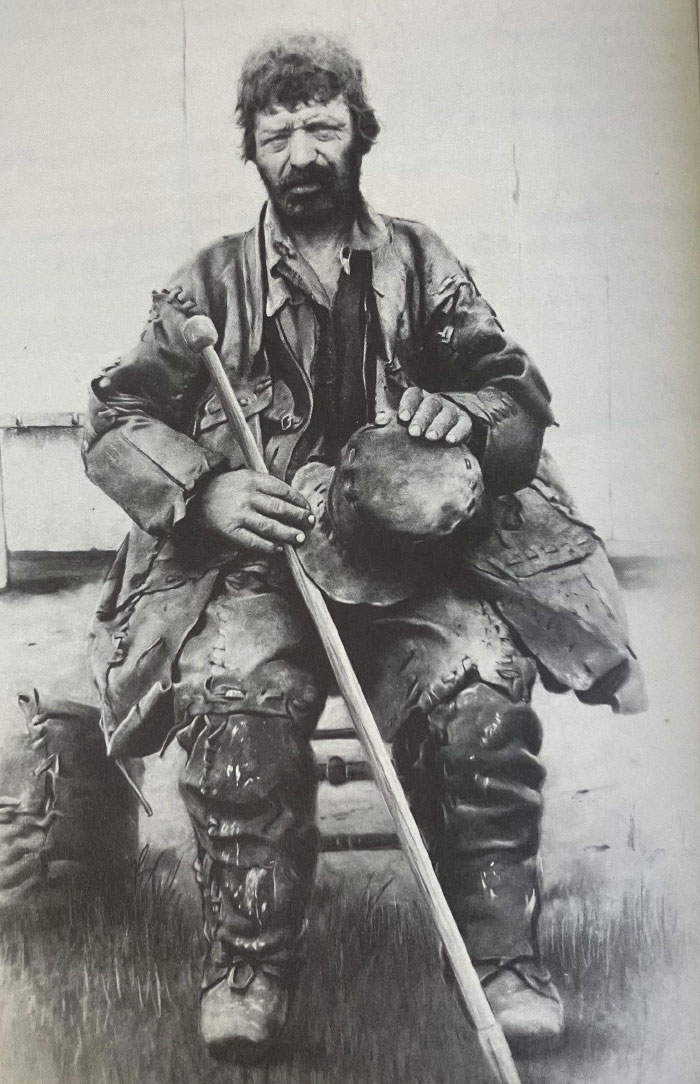

The Leatherman: A 365-Mile Mystery That Walked in Silence and Stirred Thousands He walked 365 miles every 34 days—for years—without a home, without a name. Yet everyone knew him. Wrapped head-to-toe in patchwork leather, he was a figure both out of place and perfectly at home in the wild rhythm of the American northeast.

Long before the age of digital maps, public profiles, or breaking news, a silent man carved a path not through headlines but through memory—one footfall at a time. They called him The Leatherman, and to this day, no one knows his real name, where he came from, or what haunted—or healed—him on his endless journey. Beginning in the mid-1800s, he emerged quietly, steadily, from the forests and hills of New England, following a strict, unwavering loop through Connecticut and New York—365 miles in exactly 34 days. Like clockwork. Like pilgrimage.

He passed through over 40 towns, always in the same order, always staying on schedule within a margin of hours, sometimes minutes. He never missed a stop. Never skipped a visit. No matter the season, no matter the weather—raging snowstorms, drenching rains, or the heavy, breathless heat of summer—he walked. Always walked. His only shelter: natural caves, hollowed rock overhangs, or crude stone huts. And always, the leather: more than 60 pounds of it, fashioned from old boots, discarded bags, torn coats—stitched by hand, thick and stiff, worn like armor against the world. His gear was as iconic as his silence, giving him a ghostlike quality, a wandering statue of man and myth.

He never begged. He never stole. He asked for little—usually just bread, water, or a place by the fire—and gave almost nothing in return beyond his presence. And yet, people awaited him. Children watched the roads in late afternoons, hoping to catch a glimpse. Families left food on stone walls and porches, hoping he’d stop by. Farmers, merchants, priests, and mothers—everyone knew when he was coming, and many swore they felt different after seeing him. Calmer. Grounded. Seen.

He spoke rarely, and when he did, it was said to be in a thick, broken blend of French and English, leading to speculation that he was French-Canadian, or perhaps a refugee of Europe’s mid-century wars and losses. But he never confirmed anything. He never corrected anyone. He simply kept moving. Historians, folklorists, and wanderers have long tried to piece together the puzzle. Some claim he was a heartbroken man, lost to love or guilt. Others suggest he was penitent, perhaps walking in spiritual atonement for sins no one else could see. A few proposed he suffered mental illness, but none could explain how a man so methodical, so consistent, could also be so utterly unreachable. He never gave his name.

And in 1889, after decades of walking the same loop, he [passed away] alone in a small cave near Ossining, New York. Locals found him there—his leather suit still intact, his body still curled as if simply resting. They buried him with reverence, under a simple headstone etched with only a guess at his identity: “The Leatherman.” But even [that] couldn’t unravel the mystery.

Decades later, in an effort to confirm his origins, researchers exhumed the grave—only to find… nothing. No bones. No skull. No answers. Just dirt, void, and silence. As if the earth itself had agreed to keep his secret. And so he remains—unknown, unseen, unforgettable. In our modern age, where every movement is mapped and every voice amplified, the Leatherman’s quiet journey feels almost holy. A man who built no fortune, left no writings, offered no speeches—yet who still draws respect and awe over a century later. Why? Because he showed up. Because he walked. Because in a world desperate for meaning, he offered none—and somehow, that was everything. The Leatherman didn’t ask to be remembered. But he is. Not because of what he said, but because of what he did—again and again and again. A living reminder that you don’t have to be loud to be legendary. Sometimes, walking your path—day after day—is enough.

"Tacony to Palmyra: Bridging Pennsylvania and New Jersey Since 1929"

When the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge first opened in 1929, it was more than just a link between Philadelphia and southern New Jersey—it was a bold symbol of progress and connection. Built with an elegant steel span and a functional center drawbridge, it allowed maritime traffic to pass through while ushering in a new era of regional mobility. For just five cents, early motorists could cross the Delaware River, their tires humming across the gridded steel surface. In its early days, even streetcars shared the bridge with automobiles, showcasing the blend of past and future that defined the time.

As the Great Depression loomed and the automobile age surged forward, the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge became essential for workers commuting to the city and for families seeking a weekend escape to the quieter towns of New Jersey. Its position offered a unique vantage point—smokestacks and industrial sprawl to the west, open fields and farmsteads to the east. It was more than a route; it was a transition point between two very different worlds, capturing the spirit of a growing and diversifying region.

In a time when infrastructure was becoming a backbone of American expansion, this bridge stood as a proud testament to modern engineering and regional cooperation. It didn’t just carry cars—it carried hopes, ambitions, and the rhythm of daily life. Whether you were crossing for work, leisure, or simply curiosity, the Tacony-Palmyra offered more than just passage. It provided a moment of perspective, hanging above the water like a quiet reminder of how connected, yet different, our surrounding worlds could be.

Today, nearly a century later, the bridge still stands strong, weathered by time but rich in stories. It's a piece of living history—both practical and poetic—reminding us that even something as utilitarian as a toll bridge can become a cultural touchstone when it connects not just places, but people and eras.

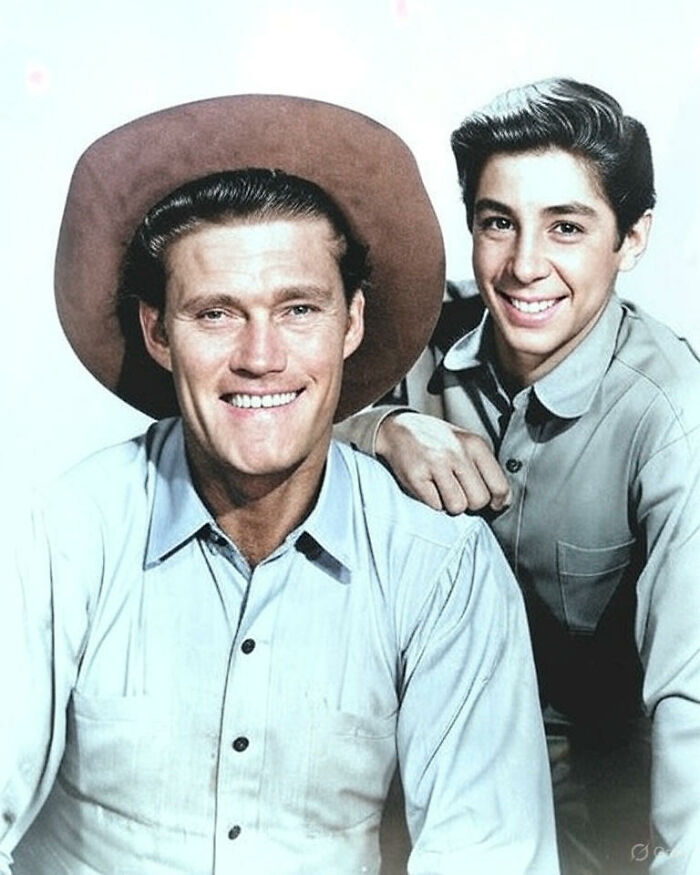

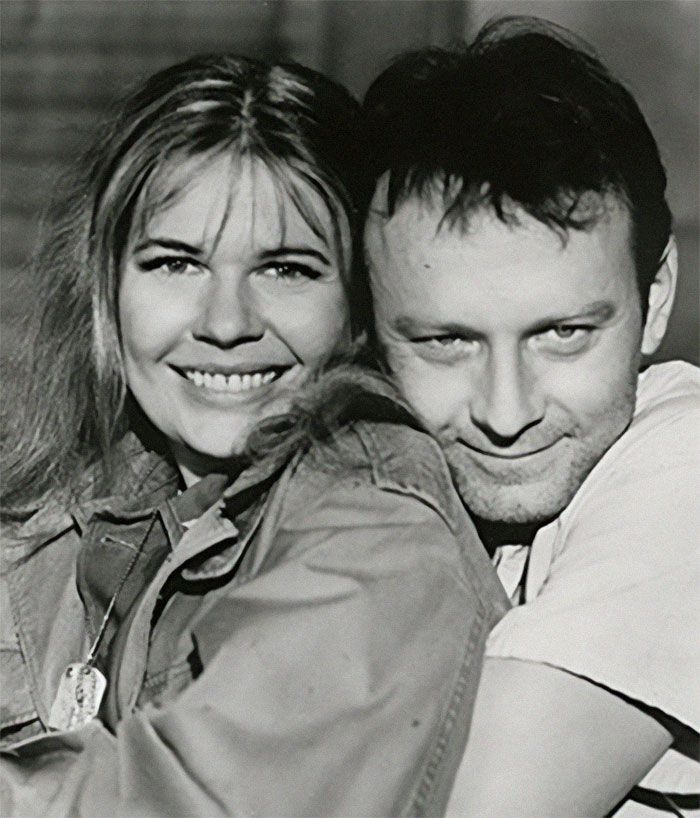

The Rifleman is a classic American Western TV series starring Chuck Connors as rancher Lucas McCain and Johnny Crawford as his son, Mark McCain. Set in the 1880s in the fictional town of North Fork, New Mexico Territory, the show was filmed in black and white and presented in half-hour episodes. It aired on ABC from September 30, 1958, to April 8, 1963, produced by Four Star Television. Notably, The Rifleman was among the first primetime television shows in the U.S. to depict a single father raising a child.

The interior of a cathedral adorned with stained glass windows is a breathtaking testament to the fusion of religious architecture and sacred art. Sunlight filters through vibrant, intricately crafted glass panels, casting kaleidoscopic patterns of color across stone floors and towering columns. Each stained glass window often depicts biblical scenes, saints, or symbolic motifs, serving both as visual storytelling and spiritual inspiration for worshippers. The soaring arches, vaulted ceilings, and ornate carvings amplify a sense of awe and reverence, guiding the eye—and the soul—upward toward the divine. This architectural masterpiece reflects centuries of devotion, craftsmanship, and theological thought, where every element is designed to evoke transcendence and connection to the sacred. Beyond their aesthetic beauty, stained glass windows also functioned historically as educational tools, communicating religious narratives to largely illiterate congregations, making the cathedral a living canvas of faith and artistry.

Loretta Swit truly held her own as head nurse Margaret Houlihan. In a special retrospective, she reflected on the onscreen relationship between “Hot Lips” and Larry Linville’s Major Frank Burns. Swit pushed back against the idea of her character being defined by an affair with a married man, advocating instead for greater depth and integrity. Determined to portray Margaret as a complex, real woman, she fought for a more mature and multifaceted evolution of the character.

In the late 1st century BC, a fierce and indomitable black queen named Amanirenas led the Kushite forces in a grueling five-year struggle against the Roman Empire. From 27 BC to 22 BC, her relentless victories slapped Rome's ambitions right in the face, thwarting their schemes to push deeper into Kush and ensuring her kingdom's freedom from Roman chains. The ancient Kingdom of Kush, now recognized as modern-day Sudan, was a force to be reckoned with, sitting just south of Egypt.

Queen Amanirenas, who ruled from 40 BC to 10 BC, was a warrior queen like no other. Losing an eye in battle only fueled her fearlessness. She made a bold statement by burying the head of Augustus Caesar's statue beneath her temple, making it clear that her people would walk over Roman pride without a second thought. Under her fearless rule, she became the bulwark against Roman advances. One of her most audacious moves was to send arrows to the Roman emperor, a message that they could either be tokens of peace or instruments of war. In the end, it was the Romans who backed down, signing a peace treaty that ushered in a golden age for Kush under her reign.

On 6 May 1900, Szmul Grin, a Polish Jew and butcher, was born in Przytyk. He was deported to Auschwitz on 24 October 1941 and registered as prisoner number 21978. He [passed away] in the camp on 1 November 1941.

Just a few days before her 100th birthday, we have to wave farewell to one of America's favorite sweethearts. She worked to support our troops during wwii, and has since been a huge part of cinema, television, stage and our hearts. Rest in peace dear Ms. Betty White, no one will ever take your place.

Abandoned Dunalastair Castle, Scotland – A Forgotten Highland Masterpiece in Ruins Tucked quietly among the moody hills and mist-draped lochs of Perthshire, Scotland, lies one of the country’s most atmospheric and poignant relics of the Victorian era: Dunalastair Castle. Now a crumbling, ivy-draped shell of its former glory, this once-stately mansion stands as a haunting monument to the passage of time, the collapse of noble dynasties, and the fading echoes of Scotland’s grand architectural past. Dunalastair Castle sits near the small village of Kinloch Rannoch, surrounded by dense forests, windswept moorland, and views of Schiehallion, one of the region’s most iconic mountains. Though often referred to as a "castle," the structure is more accurately described as a Victorian baronial mansion, constructed in the mid-19th century on the foundations of earlier dwellings that had occupied the site since the 18th century. The land itself has deep ancestral significance—it was once the seat of Clan Robertson, one of Scotland’s historic Highland clans whose lineage stretches back centuries. The current structure was built around 1859, commissioned by General Duncan Robertson of the Robertsons of Struan, as a testament to the family's heritage and growing status. Like many buildings of its era, Dunalastair Castle was conceived in the Scottish Baronial style, which combined Gothic revival motifs—turrets, battlements, crow-stepped gables—with the romantic nationalism of 19th-century Scotland. The castle's pointed towers and finely detailed stonework blended seamlessly into the rugged Highland backdrop, making it one of the region’s most admired country houses. But despite its splendor, the castle's days of grandeur were fleeting. The Robertsons eventually faced financial difficulties, and the estate passed out of the family. During World War II, like many large country homes, Dunalastair was requisitioned for military use, serving as a barracks and convalescent home. After the war, with the building in disrepair and no funds for restoration, it was abandoned. Its once-opulent interiors—wood-paneled halls, sweeping staircases, ornate drawing rooms—were left to the mercy of the elements. Over the decades, nature reclaimed its territory. Windows shattered, roofs collapsed, and ivy threaded its way through stone and timber alike. Today, Dunalastair Castle is a hauntingly beautiful ruin, locked behind fences for safety but still viewable from the nearby walking trails that wind through the estate. Its decaying walls and silent halls evoke a profound sense of nostalgia, mystery, and romantic melancholy. Photographers, urban explorers, and lovers of forgotten places are drawn to its enigmatic presence, captivated by the interplay of history, architecture, and decay. But beyond its visual allure, the castle symbolizes broader themes in Scottish history: the decline of the aristocracy, the post-war economic upheaval, and the enduring tension between heritage preservation and natural erosion. Dunalastair remains unlisted and unrestored, its future uncertain—neither fully remembered nor entirely forgotten. Whether glimpsed through morning mist or silhouetted against a fiery Highland sunset, Dunalastair Castle stands not just as an abandoned building, but as a poem in stone, whispering stories of a bygone age to all who pause long enough to listen.

More AI slop. Dunalastair 'Castle' is real. It's a 19th century country house built on a hillside and it looks nothing like the AI generated picture here. It really is dangerously unstable - don't trespass there. Bits are crumbling all the time. It's just another wealthy Victorian man's display of excess, best left to decay in peace.

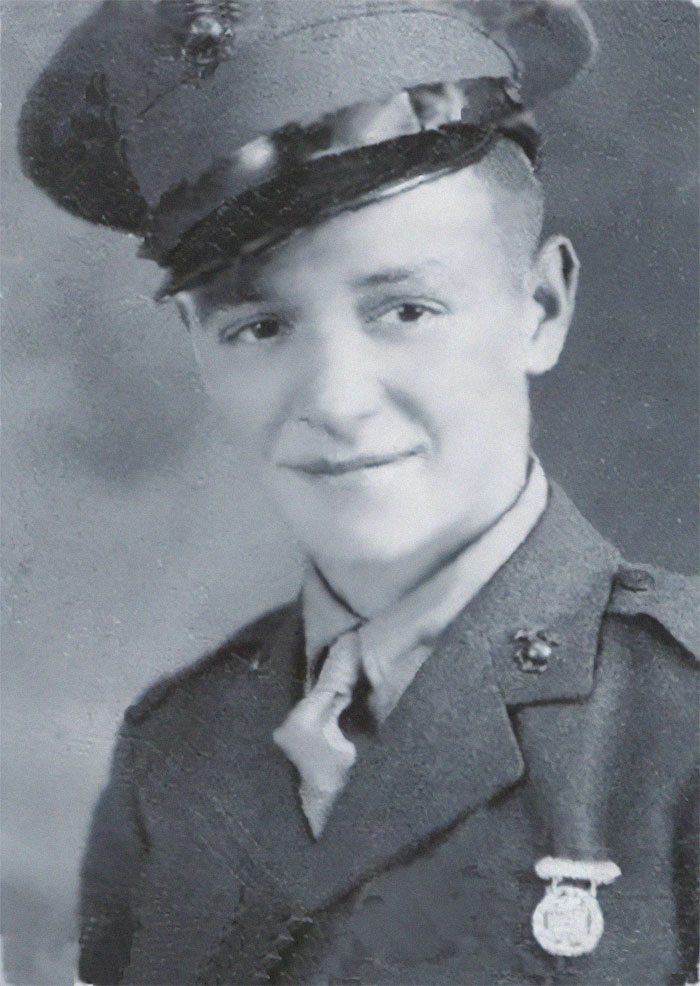

"Eighteen and Forever: The Courage and Sacrifice of PVT Ralph Howard St Clair"

On May 19, 1945, Private Ralph Howard St Clair of the United States Marine Corps fell in battle during the savage fighting on Okinawa, one of the bloodiest and most pivotal campaigns of World War II. Just 18 years old, Ralph had already seen the horrors of war—having fought on Saipan—but it was on the jagged slopes of Sugar Loaf Hill, a key strategic point in the island's defense, where his young life came to a heroic and tragic end.

He served with D Company, 2nd Battalion, 29th Marines, 6th Marine Division, operating as a scout and automatic rifleman in some of the most dangerous terrain and under some of the fiercest enemy fire the Pacific War had to offer. Born on December 1, 1926, in Amsterdam, New York, Ralph was the son of Fred and Mary St. Clair.

His father, Fred, a veteran of the First World War, likely understood too well the risks his son faced in service. The family’s sacrifice deepened when Fred passed away just five weeks after Ralph, perhaps from grief as much as age, on June 26, 1945. It was a heartbreaking chapter for a family that had given more than most—across two world wars and two generations.

At first, Ralph was listed as Missing in Action, his fate uncertain for over a decade. But in 1956, Ralph’s remains were finally recovered and identified, bringing long-awaited closure to his loved ones. At his mother Mary’s request, he was laid to rest with honor in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii, also known as the Punchbowl, among thousands of other fallen heroes. His grave rests in Section G, Site 535, a solemn tribute to a boy who gave his life in service of something larger than himself. Today, we remember PVT Ralph Howard St Clair not just as a name etched in stone, but as a brave young man who stood tall in the face of unimaginable peril. His youth was stolen by war, but his courage endures—etched into history at Okinawa, remembered in the quiet grass of Honolulu, and honored by all who understand the true cost of freedom.

Sun, Sand, and Spring Break: Fort Lauderdale in Its Flashiest Era

This 1980 snapshot of Fort Lauderdale Beach captures the city just as it was becoming a cultural icon of sun-soaked freedom, flashy cars, and endless Spring Breaks. By the late 1970s and into the 1980s, Fort Lauderdale had become the go-to destination for college students looking to cut loose. The beach strip buzzed with energy—radio stations broadcasted live from bars, neon signs lit up the night, and traffic crawled as convertibles paraded up and down A1A.

Originally a quiet coastal retreat, Fort Lauderdale began attracting large numbers of Spring Breakers after World War II. But it was the 1960 film Where the Boys Are that turned the city into a national symbol of youth and beach-party rebellion. By 1980, the crowds had ballooned to hundreds of thousands during Spring Break season, drawing both excitement and growing concern from locals and city officials.

The beach itself, with its wide sandy shores and recognizable wave wall, became the backdrop for a blend of old Florida charm and new, fast-paced pop culture. Bathing suits were skimpier, music was louder, and the vibe was unmistakably ‘80s—carefree, colorful, and just a little bit wild. Vendors, rollerbladers, and sunbathers created a collage of activity that defined Fort Lauderdale’s beach strip for a generation.

Though the city would later crack down on unruly Spring Break crowds in the mid-1980s, Fort Lauderdale Beach in 1980 represents a golden moment of American youth culture at its boldest. This image freezes that moment in time—when all you needed was a boombox, a tan, and a spot in the sand.

Formal portraits rarely featured smiles, but they can be found in photographs of daily life during this period. (1912, South Carolina.)

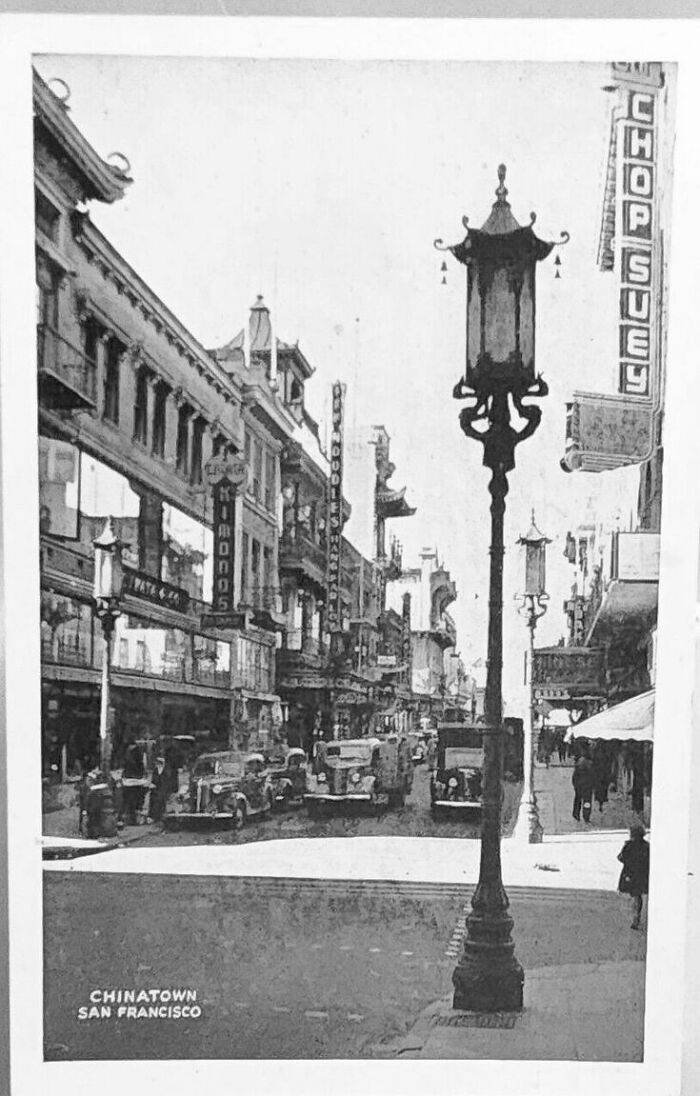

Vintage 1940's RPPC of "Chinatown", San Francisco, CA, USA

Without even reading the notation, I could recognize this as Grant Ave.

“Daughter of white tobacco sharecropper at country store. Person County, North Carolina.”

By Dorothea Lange - July, 1939.

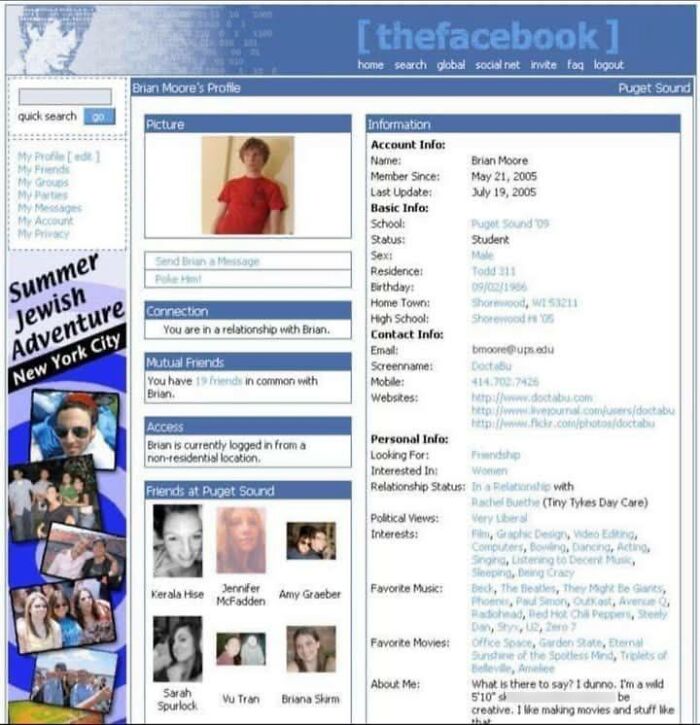

The very first Facebook layout, 2004.

This was the very first Facebook layout, launched in 2004 when the platform was still known as Thefacebook. Created by Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg, it began as a campus-exclusive social network designed to connect college students through profile pages, class schedules, and friend lists. The interface was stark—minimal design, no news feed, and certainly no ads—but it laid the foundation for what would become one of the most influential platforms in internet history.

At launch, Thefacebook was limited to Harvard students only. Users needed a valid .edu email address to sign up, and the site was primarily used to view classmates' profiles and connect socially within the campus ecosystem. Each user’s page showed a photo, basic information, and a "social network" of friends—a digital yearbook for the early 2000s.

The original layout featured a prominent banner, basic search, and a profile-based navigation system. It lacked the features we now take for granted—no timelines, no reactions, no algorithmic feeds—but it rapidly gained popularity for its simplicity and exclusivity. By the end of 2004, it had expanded to dozens of universities across the United States.

This modest interface marked the beginning of a social media revolution. What started as a dorm-room project would evolve into a global platform shaping how billions of people communicate, share, and connect. Looking back at this early design is like peering into the digital past—a reminder of how far the internet has come in just two decades.

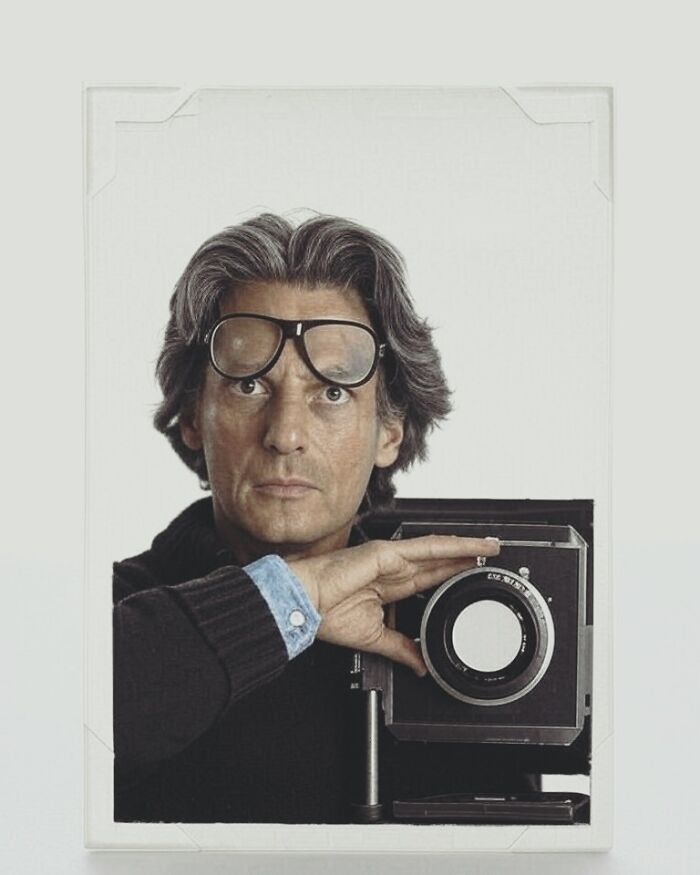

"Through the Lens of Elegance: Richard Avedon, Born May 15, 1923"

On May 15, 1923, the world welcomed Richard Avedon, a man whose camera would forever transform the way we see beauty, celebrity, and the very soul of a photograph. Known for his pioneering work in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and countless iconic campaigns, Avedon didn’t just take pictures—he told stories. Whether it was a model caught mid-stride in a Dior gown or a weathered face of an American worker, his images struck a rare balance between style and substance, redefining photography as both art and cultural commentary.

Avedon's fashion work was dynamic and alive. In an era when most fashion photography was rigid and posed, he dared to infuse movement, attitude, and emotion. His collaboration with model Dovima and an elephant in a Paris circus remains one of the most unforgettable images in fashion history—a stunning blend of elegance and surrealism. Yet, beyond the glossy pages of haute couture, Avedon was also deeply drawn to the depth of human expression, photographing the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Charlie Chaplin, and countless others not just as icons, but as vulnerable, complex individuals.

The New York Times once wrote that "his fashion and portrait photographs helped define America's image of style, beauty and culture for the last half-century." And it’s true—Avedon’s lens became a mirror reflecting America’s evolving ideals, its contradictions, and its dreams. In projects like In the American West, he turned his eye toward ranchers, miners, and drifters—capturing their rugged honesty with the same care he gave to magazine covers. He erased the boundary between the elite and the everyday, insisting that every face held a story worth telling.

Richard Avedon passed away in 2004, but his influence is still everywhere—from modern editorial spreads to contemporary portraiture. His work invites us to look closer, to find beauty in movement, power in simplicity, and truth in the unguarded moment. On what would have been his birthday, we remember not just a photographer, but a visionary who taught us how to see.

Nestled within the rose-red cliffs of Petra, a wealthy merchant’s house was carved directly into the sandstone walls—both a home and a symbol of Nabataean prosperity. The façade, though modest compared to Petra’s grand tombs, bore intricate carvings hinting at trade connections with Rome, Arabia, and the Silk Road. Inside, the house was cool and shaded, with light filtering in through narrow fissures in the rock, casting golden beams onto polished stone floors. Niches in the walls held imported goods—perfume jars, Roman glass, silk, and spices—evidence of a thriving trade empire. Water channels etched into the stone funneled runoff into hidden cisterns, showcasing advanced desert engineering. This dwelling wasn’t merely a shelter—it was a command post for transcontinental commerce, where contracts were written and fortunes changed by oil-lamp flicker and sunlight shard.

What? I thought this was the Treasury? "The Treasury was not a treasury - but a mausoleum for the 1st century AD Nabatean King Aretas IV, later used as a place of worship."

Hollywood Glamor Meets the Thrill of the Track: Raft & Grable at Belmont Park, 1939

Captured by famed photographer Bert Morgan, this 1939 photo shows Hollywood stars George Raft and Betty Grable enjoying a day at Belmont Park Racetrack in Elmont, New York. Raft, known for his suave gangster roles and sharp style, was one of the era’s top leading men, while Grable was America’s sweetheart, famous for her singing, dancing, and iconic pin-up status during World War II. Together, they brought a touch of Tinseltown glamor to the excitement of horse racing.

Belmont Park was already a celebrated venue in the late 1930s, hosting prestigious events like the Belmont Stakes, the final jewel in the Triple Crown. The racetrack attracted celebrities, socialites, and racing enthusiasts alike, blending sport with social spectacle. Photos like this reveal how stars of the silver screen often escaped their studio sets to enjoy the vibrant public life of New York.

The year 1939 was a golden moment in American film and culture, marked by classic movie releases and a nation on the brink of wartime transformation. In this candid snapshot, Raft and Grable appear relaxed and engaged—offering a glimpse of the personal lives behind the glamour and fame.

Today, this image serves as a nostalgic reminder of an era when Hollywood and high society intersected seamlessly, and the roar of the crowd at Belmont echoed alongside the applause of the movie theaters.

Beneath the blazing sands of Giza, where the mighty pyramids pierce the sky, some experts believe an ancient secret lies hidden: a vast underground city. For decades, whispers of mysterious tunnels and chambers buried deep below the pyramids have sparked both wonder and controversy.

Could there be forgotten passageways, sacred vaults, or even hidden libraries beneath Egypt’s most iconic monuments? A few daring researchers claim to have found evidence—traces of sealed entrances and unexplained voids—hinting at a lost subterranean world. While mainstream archaeology remains cautious, the theory invites us to reimagine the past: what if the pyramids were not just tombs, but gateways to something deeper? Something older? With every grain of sand removed and every chamber scanned, the ancient ground beneath Giza may yet reveal a truth stranger than legend.

Why is BP running this utter nonsense generated by AI? No experts claim anything of the sort. Yes, some researchers have suggested there's odd stuff underneath on the basis of radar scanning by space satellites 420 miles up (no, really), but those claims have been investigated and thoroughly debunked. The first link I found follows - there's more out there on the subject.

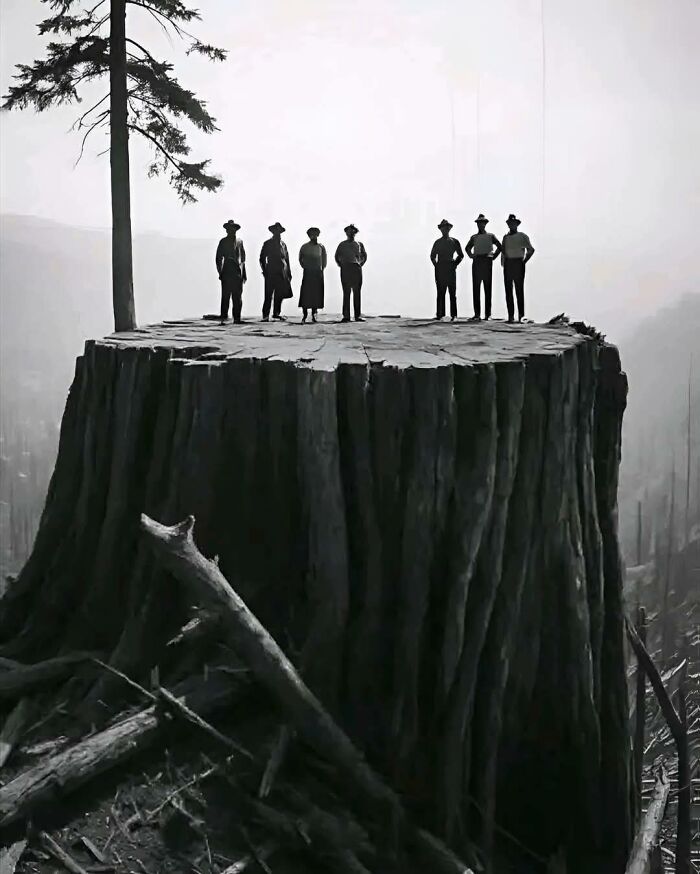

The Last Giant Silicon Tree: A Living Monument to Nature’s Majesty

In the waning years of the 19th century, in the year 1899, a photograph was taken that would come to symbolize not only the fading splendor of an ancient natural world but also the profound tension between progress and preservation. This image, now revered as a historical and ecological treasure, immortalized the Last Giant Silicon Tree—a towering marvel of the natural world, whose presence stood as a living chronicle of Earth’s ancient past.

The tree, colossal in scale and unfathomably old, loomed above the forest canopy like a sentinel from another age. Its bark, weathered by centuries of storms and seasons, bore the rugged textures of endurance. The branches spread out like the arms of a sleeping titan, and its leaves shimmered in the light with a quiet dignity that belied its immense strength. Standing among the largest known trees of its kind, the Silicon Tree was unlike any other; it rose from the earth with an aura of solemn grace, seemingly untouched by time. Local indigenous communities had long regarded it as sacred, attributing spiritual significance to its size, age, and resilience.

What set the Silicon Tree apart was not only its remarkable size—measuring hundreds of feet into the sky—but its composition and endurance. Scientists of the era, equipped with rudimentary tools and a growing curiosity about the natural world, were captivated by the tree’s unique qualities. It earned its name from the silicate-rich properties in its trunk and leaves, a rare biological adaptation believed to have contributed to its exceptional lifespan. Some speculated that the tree had witnessed millennia unfold, its roots entangled with the earliest civilizations, its canopy brushing the skies of forgotten eras.

Explorers, naturalists, and photographers flocked to the remote forest where the tree stood, enduring treacherous journeys through rugged terrain to behold what many described as nature’s cathedral. The photograph taken in 1899 captured not just the physical likeness of the tree, but its overwhelming presence—its defiant stance amid an age of accelerating human encroachment. At a time when the industrial revolution was reshaping landscapes, extracting resources, and redrawing the balance between man and nature, the image of the Silicon Tree offered a powerful counter-narrative. It was a moment of stillness, a breath held in reverence, as if the Earth itself paused to be remembered.

But this symbol of strength also carried a weight of sorrow. By the end of the 19th century, deforestation had already begun to claim many of Earth’s oldest living giants. Logging, once a local practice, had become an engine of global demand, feeding the appetites of expanding cities, railroads, and factories. Forests that had stood for thousands of years were vanishing in mere decades. The Last Giant Silicon Tree, while spared temporarily by its isolation, soon came to be seen as the final survivor of a vanishing lineage. It stood alone, not just in stature, but in symbolism—as the last echo of a primordial forest that had once covered vast swaths of the continent.

The photograph, initially circulated in scientific journals and newspapers, quickly spread beyond academic circles. It inspired awe in the public imagination and ignited some of the earliest conversations about conservation. Environmental pioneers cited the image in speeches and writings, arguing for the urgent need to protect Earth’s irreplaceable biological heritage. For many, it was the first time they had truly grasped the idea that nature could be lost forever.

As the 20th century dawned, the world moved steadily into a new age—an era defined by invention, industry, and unprecedented growth. Yet amid the noise of factories and the laying of iron rails, the image of the Last Giant Silicon Tree endured. It became a touchstone for naturalists, artists, and poets who saw in it both a monument to nature’s former glory and a plea for restraint in the face of progress.

Today, more than a century later, the photograph remains a potent symbol. Housed in museums, archives, and digital collections, it continues to provoke reflection and reverence. It reminds us of a time when the world still held unexplored wonders, when a single tree could humble the ambitions of empires. It speaks to the resilience of the Earth and the fragility of its most ancient forms of life. And above all, it challenges us to consider what kind of legacy we wish to leave behind.

The Last Giant Silicon Tree may no longer stand, its trunk perhaps long since fallen and returned to the soil. But its spirit lives on in that singular image—a sepia-toned testament to the majesty of the natural world and the eternal importance of preserving it for those yet to come.

I had to downvote a greater number of these than I wanted because the photos were great but the accompanying text appeared to be bullshit. A quick few descriptive sentences for us would have been fine, but these cascading paragraphs of garbage were excruciating. If a real person wrote these articles, I am sorry but you need to go back to school to learn how to write. If this was AI, your AI program is not up to snuff and you need to get your money back.

Interesting photos, but too many of the captions do read like AI slop. I think that because the same amount of information could be conveyed with a quarter of the words or less in many cases - all the long-winded captions are padded out with huge amounts of filler text.

I had to downvote a greater number of these than I wanted because the photos were great but the accompanying text appeared to be bullshit. A quick few descriptive sentences for us would have been fine, but these cascading paragraphs of garbage were excruciating. If a real person wrote these articles, I am sorry but you need to go back to school to learn how to write. If this was AI, your AI program is not up to snuff and you need to get your money back.

Interesting photos, but too many of the captions do read like AI slop. I think that because the same amount of information could be conveyed with a quarter of the words or less in many cases - all the long-winded captions are padded out with huge amounts of filler text.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime