With millions of pictures taken every day, we can easily get lost in the vast world of images. That's why TIME magazine decided to create a list of the 100 most influential pictures ever taken. They teamed up with curators, historians, photo editors, and famous photographers around the world for this task. And now, you can find all of the most famous photos in one place, together with descriptions as to why these famous historical photos are such an important part of our legacy.

"No formula makes for iconic photos," the editors said. "Some rare historical photos are on our list because they were the first of their kind, others because they shaped the way we think. And some cut because they directly changed the way we live. What all of the 100 famous photos share is that they are turning points in our human experience."

The result they ended up with is not only a collection of superb historical photos but incredible human experiences as well. "The best photography is a form of bearing witness, a way of bringing a single vision to the larger world."

Ready to explore the world in a new view through the most famous photos of all time? If so, grab a cup of your favorite beverage and prepare for a journey that might just change the way you look at the world. The photo gallery of the most famous pictures of our age is right at your fingertips!

More info: time.com

This post may include affiliate links.

Lunch Atop A Skyscraper, 1932

It’s the most perilous yet playful lunch break ever captured: 11 men casually eating, chatting and sneaking a smoke as if they weren’t 840 feet above Manhattan with nothing but a thin beam keeping them aloft. That comfort is real; the men are among the construction workers who helped build Rockefeller Center. But the picture, taken on the 69th floor of the flagship RCA Building (now the GE Building), was staged as part of a promotional campaign for the massive skyscraper complex. While the photographer and the identities of most of the subjects remain a mystery—the photographers Charles C. Ebbets, Thomas Kelley and William Leftwich were all present that day, and it’s not known which one took it—there isn’t an ironworker in New York City who doesn’t see the picture as a badge of their bold tribe. In that way they are not alone. By thumbing its nose at both danger and the Depression, Lunch Atop a Skyscraper came to symbolize American resilience and ambition at a time when both were desperately needed. It has since become an iconic emblem of the city in which it was taken, affirming the romantic belief that New York is a place unafraid to tackle projects that would cow less brazen cities. And like all symbols in a city built on hustle, Lunch Atop a Skyscraper has spawned its own economy. It is the Corbis photo agency’s most reproduced image. And good luck walking through Times Square without someone hawking it on a mug, magnet or T-shirt.

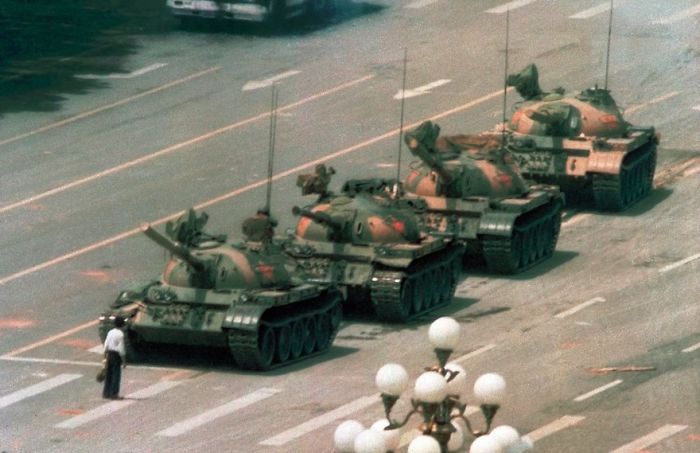

Tank Man, Jeff Widener, 1989

On the morning of June 5, 1989, photographer Jeff Widener was perched on a sixth-floor balcony of the Beijing Hotel. It was a day after the Tiananmen Square massacre, when Chinese troops attacked pro-democracy demonstrators camped on the plaza, and the Associated Press sent Widener to document the aftermath. As he photographed bloody victims, passersby on bicycles and the occasional scorched bus, a column of tanks began rolling out of the plaza. Widener lined up his lens just as a man carrying shopping bags stepped in front of the war machines, waving his arms and refusing to move.

The tanks tried to go around the man, but he stepped back into their path, climbing atop one briefly. Widener assumed the man would be killed, but the tanks held their fire. Eventually the man was whisked away, but not before Widener immortalized his singular act of resistance. Others also captured the scene, but Widener’s image was transmitted over the AP wire and appeared on front pages all over the world. Decades after Tank Man became a global hero, he remains unidentified. The anonymity makes the photograph all the more universal, a symbol of resistance to unjust regimes everywhere.

Earthrise, William Anders, NASA, 1968

It’s never easy to identify the moment a hinge turns in history. When it comes to humanity’s first true grasp of the beauty, fragility and loneliness of our world, however, we know the precise instant. It was on December 24, 1968, exactly 75 hours, 48 minutes and 41 seconds after the Apollo 8 spacecraft lifted off from Cape Canaveral en route to becoming the first manned mission to orbit the moon. Astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders entered lunar orbit on Christmas Eve of what had been a bloody, war-torn year for America. At the beginning of the fourth of 10 orbits, their spacecraft was emerging from the far side of the moon when a view of the blue-white planet filled one of the hatch windows. “Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Anders exclaimed. He snapped a picture—in black and white. Lovell scrambled to find a color canister. “Well, I think we missed it,” Anders said. Lovell looked through windows three and four. “Hey, I got it right here!” he exclaimed. A weightless Anders shot to where Lovell was floating and fired his Hasselblad. “You got it?” Lovell asked. “Yep,” Anders answered. The image—our first full-color view of our planet from off of it—helped to launch the environmental movement. And, just as important, it helped human beings recognize that in a cold and punishing cosmos, we’ve got it pretty good.

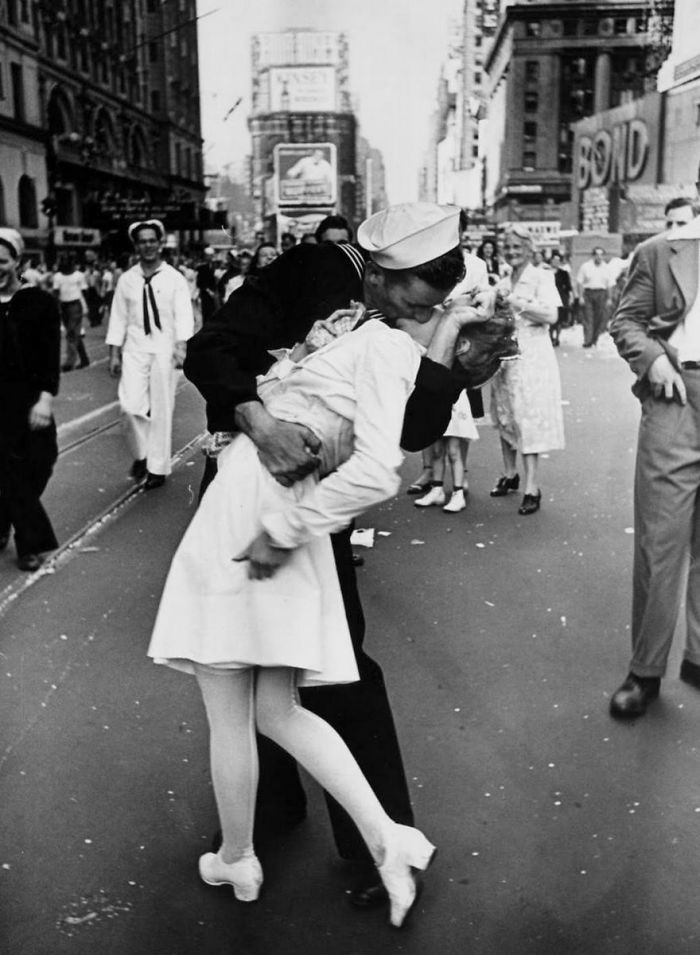

V-J Day In Times Square, Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1945

At its best, photography captures fleeting snippets that crystallize the hope, anguish, wonder and joy of life. Alfred Eisenstaedt, one of the first four photographers hired by LIFE magazine, made it his mission “to find and catch the storytelling moment.” He didn’t have to go far for it when World War II ended on August 14, 1945. Taking in the mood on the streets of New York City, Eisenstaedt soon found himself in the joyous tumult of Times Square. As he searched for subjects, a sailor in front of him grabbed hold of a nurse, tilted her back and kissed her. Eisenstaedt’s photograph of that passionate swoop distilled the relief and promise of that momentous day in a single moment of unbridled joy (although some argue today that it should be seen as a case of sexual assault). His beautiful image has become the most famous and frequently reproduced picture of the 20th century, and it forms the basis of our collective memory of that transformative moment in world history. “People tell me that when I’m in heaven,” Eisenstaedt said, “they will remember this picture.”

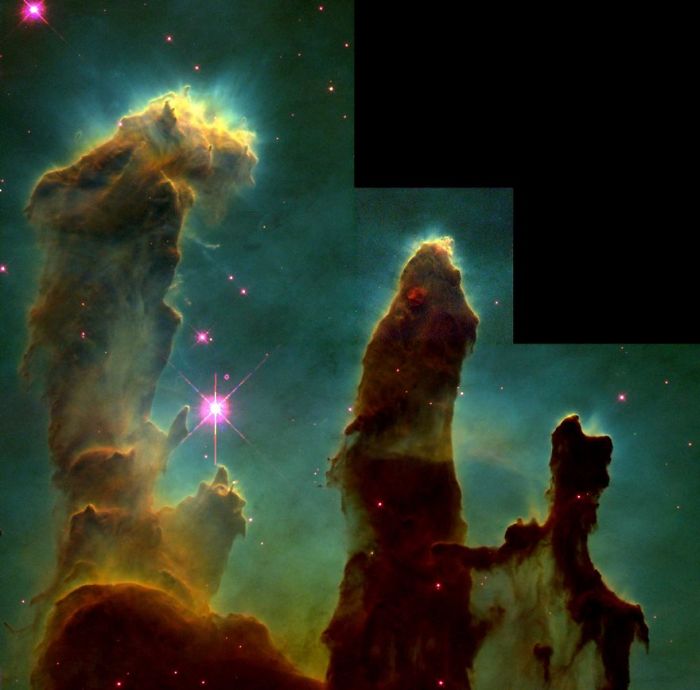

Pillars Of Creation, Nasa, 1995

The Hubble Space Telescope almost didn’t make it. Carried aloft in 1990 aboard the space shuttle Atlantis, it was over-budget, years behind schedule and, when it finally reached orbit, nearsighted, its 8-foot mirror distorted as a result of a manufacturing flaw. It would not be until 1993 that a repair mission would bring Hubble online. Finally, on April 1, 1995, the telescope delivered the goods, capturing an image of the universe so clear and deep that it has come to be known as Pillars of Creation. What Hubble photographed is the Eagle Nebula, a star-forming patch of space 6,500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Serpens Cauda. The great smokestacks are vast clouds of interstellar dust, shaped by the high-energy winds blowing out from nearby stars (the black portion in the top right is from the magnification of one of Hubble’s four cameras). But the science of the pillars has been the lesser part of their significance. Both the oddness and the enormousness of the formation—the pillars are 5 light-years, or 30 trillion miles, long—awed, thrilled and humbled in equal measure. One image achieved what a thousand astronomy symposia never could.

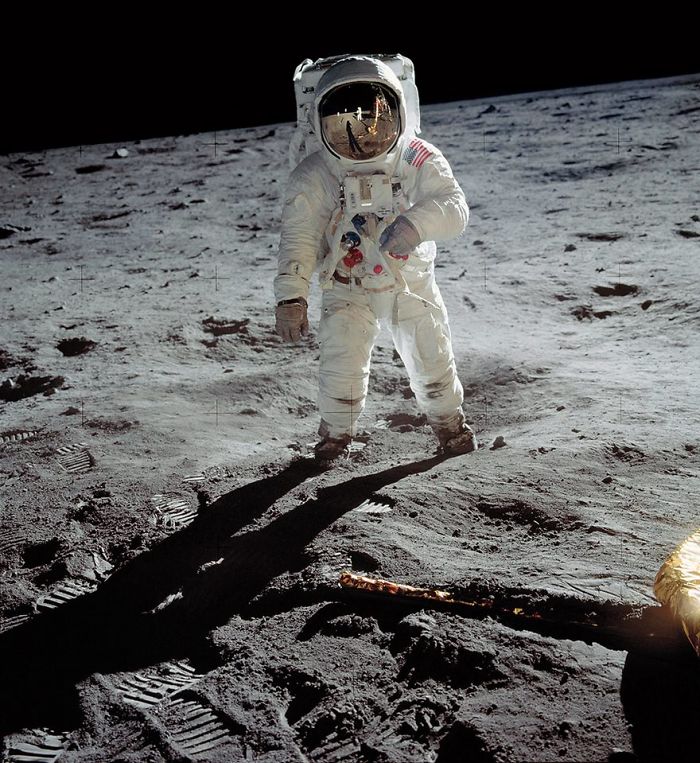

A Man On The Moon, Neil Armstrong, Nasa, 1969

Somewhere in the Sea of Tranquillity, the little depression in which Buzz Aldrin stood on the evening of July 20, 1969, is still there—one of billions of pits and craters and pockmarks on the moon’s ancient surface. But it may not be the astronaut’s most indelible mark.

Aldrin never cared for being the second man on the moon—to come so far and miss the epochal first-man designation Neil Armstrong earned by a mere matter of inches and minutes. But Aldrin earned a different kind of immortality. Since it was Armstrong who was carrying the crew’s 70-millimeter Hasselblad, he took all of the pictures—meaning the only moon man earthlings would see clearly would be the one who took the second steps. That this image endured the way it has was not likely. It has none of the action of the shots of Aldrin climbing down the ladder of the lunar module, none of the patriotic resonance of his saluting the American flag. He’s just standing in place, a small, fragile man on a distant world—a world that would be happy to kill him if he removed so much as a single article of his exceedingly complex clothing. His arm is bent awkwardly—perhaps, he has speculated, because he was glancing at the checklist on his wrist. And Armstrong, looking even smaller and more spectral, is reflected in his visor. It’s a picture that in some ways did everything wrong if it was striving for heroism. As a result, it did everything right.

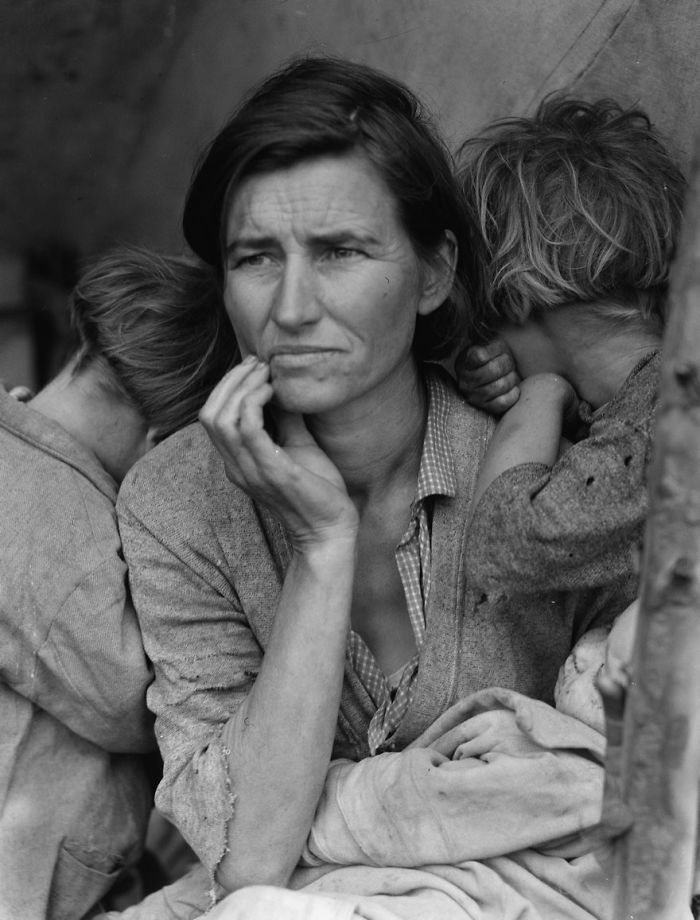

Migrant Mother, Dorothea Lange, 1936

The picture that did more than any other to humanize the cost of the Great Depression almost didn’t happen. Driving past the crude “Pea-Pickers Camp” sign in Nipomo, north of Los Angeles, Dorothea Lange kept going for 20 miles. But something nagged at the photographer from the government’s Resettlement Administration, and she finally turned around. At the camp, the Hoboken, N.J.–born Lange spotted Frances Owens Thompson and knew she was in the right place. “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother in the sparse lean-to tent, as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange later wrote. The farm’s crop had frozen, and there was no work for the homeless pickers, so the 32-year-old Thompson sold the tires from her car to buy food, which was supplemented with birds killed by the children. Lange, who believed that one could understand others through close study, tightly framed the children and the mother, whose eyes, worn from worry and resignation, look past the camera. Lange took six photos with her 4x5 Graflex camera, later writing, “I knew I had recorded the essence of my assignment.” Afterward Lange informed the authorities of the plight of those at the encampment, and they sent 20,000 pounds of food. Of the 160,000 images taken by Lange and other photographers for the Resettlement Administration, Migrant Mother has become the most iconic picture of the Depression. Through an intimate portrait of the toll being exacted across the land, Lange gave a face to a suffering nation.

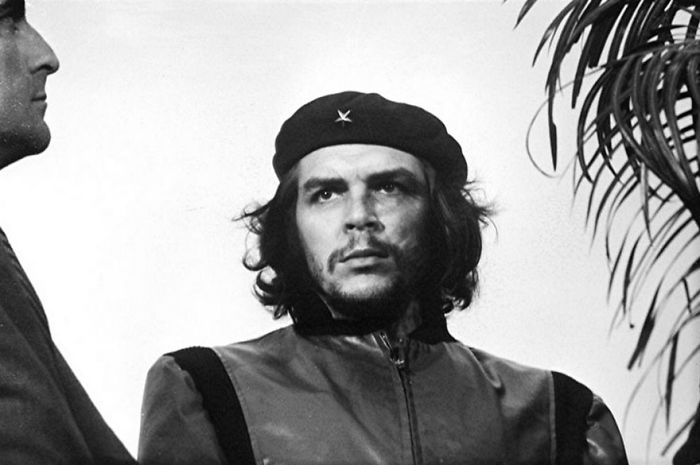

Guerillero Heroico, Alberto Korda, 1960

The day before Alberto Korda took his iconic photograph of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, a ship had exploded in Havana Harbor, killing the crew and dozens of dockworkers. Covering the funeral for the newspaper Revolución, Korda focused on Fidel Castro, who in a fiery oration accused the U.S. of causing the explosion. The two frames he shot of Castro’s young ally were a seeming afterthought, and they went unpublished by the newspaper. But after Guevara was killed leading a guerrilla movement in Bolivia nearly seven years later, the Cuban regime embraced him as a martyr for the movement, and Korda’s image of the beret-clad revolutionary soon became its most enduring symbol. In short order, Guerrillero Heroico was appropriated by artists, causes and admen around the world, appearing on everything from protest art to underwear to soft drinks. It has become the cultural shorthand for rebellion and one of the most recognizable and reproduced images of all time, with its influence long since transcending its steely-eyed subject.

Dalí Atomicus, Philippe Halsman, 1948

Capturing the essence of those he photographed was Philippe Halsman’s life’s work. So when Halsman set out to shoot his friend and longtime collaborator the Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, he knew a simple seated portrait would not suffice. Inspired by Dalí’s painting Leda Atomica, Halsman created an elaborate scene to surround the artist that included the original work, a floating chair and an in-progress easel suspended by thin wires. Assistants, including Halsman’s wife and young daughter Irene, stood out of the frame and, on the photographer’s count, threw three cats and a bucket of water into the air while Dalí leaped up. It took the assembled cast 26 takes to capture a composition that satisfied Halsman. And no wonder. The final result, published in LIFE, evokes Dalí’s own work. The artist even painted an image directly onto the print before publication.

Before Halsman, portrait photography was often stilted and softly blurred, with a clear sense of detachment between the photographer and the subject. Halsman’s approach, to bring subjects such as Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe and Alfred Hitchcock into sharp focus as they moved before the camera, redefined portrait photography and inspired generations of photographers to collaborate with their subjects.

View From The Window At Le Gras, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, 1826

It took a unique combination of ingenuity and curiosity to produce the first known photograph, so it’s fitting that the man who made it was an inventor and not an artist. In the 1820s, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce had become fascinated with the printing method of lithography, in which images drawn on stone could be reproduced using oil-based ink. Searching for other ways to produce images, Niépce set up a device called a camera obscura, which captured and projected scenes illuminated by sunlight, and trained it on the view outside his studio window in eastern France. The scene was cast on a treated pewter plate that, after many hours, retained a crude copy of the buildings and rooftops outside. The result was the first known permanent photograph.

It is no overstatement to say that Niépce’s achievement laid the groundwork for the development of photography. Later, he worked with artist Louis Daguerre, whose sharper daguerreotype images marked photography’s next major advancement.

Leap Into Freedom, Peter Leibing, 1961

Following World War II, the conquering Allied governments carved Berlin into four occupation zones. Yet each part was not equal, and from 1949 to 1961 some 2.5 million East Germans fled the Soviet section in search of freedom. To stop the flow, East German leader Walter Ulbricht had a barbed-wire-and-cinder-block barrier thrown up in early August 1961. A few days later, Associated Press photographer Peter Leibing was tipped off that a defection might happen. He and other cameramen gathered and watched as a West Berlin crowd enticed 19-year-old border guard Hans Conrad Schumann, yelling to him, “Come on over!” Schumann, who later said he did not want to “live enclosed,” suddenly ran for the barricade. As he cleared the sharp wires he dropped his rifle and was whisked away. Sent out across the AP wire, Leibing’s photo ran on front pages across the world. It made Schumann, reportedly the first known East German soldier to flee, into a poster child for those yearning to be free, while lending urgency to East Germany’s push for a more permanent Berlin Wall. Schumann was sadly haunted by the weight of it all. While he quietly lived in the West, he could not grapple with his unintended stature as a symbol of freedom, and he committed suicide in 1998.

The Hand Of Mrs. Wilhelm Röntgen, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, 1895

There’s no way of knowing how many pictures were taken of Anna Bertha Röntgen, and most are surely lost to history. But one of them isn’t: it is of her hand—more precisely, the bones in her hand—an image captured by her husband Wilhelm when he took the first medical x-ray in 1895. Wilhelm had spent weeks working in his lab, experimenting with a cathode tube that emitted different frequencies of electromagnetic energy. Some, he noticed, appeared to penetrate solid objects and expose sheets of photographic paper. He used the strange rays, which he aptly dubbed x-rays, to create shadowy images of the inside of various inanimate objects and then, finally, one very animate one. The picture of Anna’s hand created a sensation, and the discovery of x-rays won Wilhelm the first Nobel Prize ever granted for physics in 1901. His breakthrough quickly went into use around the world, revolutionizing the diagnosis and treatment of injuries and illnesses that had always been hidden from sight. Anna, however, was never taken with the picture. “I have seen my death,” she said when she first glimpsed it. For many millions of other people, it has meant life.

Flag Raising On Iwo Jima, Joe Rosenthal, 1945

It is but a speck of an island 760 miles south of Tokyo, a volcanic pile that blocked the Allies’ march toward Japan. The Americans needed Iwo Jima as an air base, but the Japanese had dug in. U.S. troops landed on February 19, 1945, beginning a month of fighting that claimed the lives of 6,800 Americans and 21,000 Japanese. On the fifth day of battle, the Marines captured Mount Suribachi. An American flag was quickly raised, but a commander called for a bigger one, in part to inspire his men and demoralize his opponents. Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal lugged his bulky Speed Graphic camera to the top, and as five Marines and a Navy corpsman prepared to hoist the Stars and Stripes, Rosenthal stepped back to get a better frame—and almost missed the shot. “The sky was overcast,” he later wrote of what has become one of the most recognizable images of war. “The wind just whipped the flag out over the heads of the group, and at their feet the disrupted terrain and the broken stalks of the shrubbery exemplified the turbulence of war.” Two days later Rosenthal’s photo was splashed on front pages across the U.S., where it was quickly embraced as a symbol of unity in the long-fought war. The picture, which earned Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize, so resonated that it was made into a postage stamp and cast as a 100-ton bronze memorial.

Cotton Mill Girl, Lewis Hine, 1908

Working as an investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, Lewis Hine believed that images of child labor would force citizens to demand change. The muckraker conned his way into mills and factories from Massachusetts to South Carolina by posing as a Bible seller, insurance agent or industrial photographer in order to tell the plight of nearly 2 million children. Carting around a large-format camera and jotting down information in a hidden notebook, Hine recorded children laboring in meatpacking houses, coal mines and canneries, and in November 1908 he came upon Sadie Pfeifer, who embodied the world he exposed. A 48-inch-tall wisp of a girl, she was “one of the many small children at work” manning a gargantuan cotton-spinning machine in Lancaster, S.C. Since Hine often had to lie to get his shots, he made “double-sure that my photo data was 100% pure—no retouching or fakery of any kind.” His images of children as young as 8 dwarfed by the cogs of a cold, mechanized universe squarely set the horrors of child labor before the public, leading to regulatory legislation and cutting the number of child laborers nearly in half from 1910 to 1920.

Fetus, 18 Weeks, Lennart Nilsson, 1965

When LIFE published Lennart Nilsson’s photo essay “Drama of Life Before Birth” in 1965, the issue was so popular that it sold out within days. And for good reason. Nilsson’s images publicly revealed for the first time what a developing fetus looks like, and in the process raised pointed new questions about when life begins. In the accompanying story, LIFE explained that all but one of the fetuses pictured were photographed outside the womb and had been removed—or aborted—“for a variety of medical reasons.” Nilsson had struck a deal with a hospital in Stockholm, whose doctors called him whenever a fetus was available to photograph. There, in a dedicated room with lights and lenses specially designed for the project, Nilsson arranged the fetuses so they appeared to be floating as if in the womb.

In the years since Nilsson’s essay was published, the images have been widely appropriated without his permission. Antiabortion activists in particular have used them to advance their cause. (Nilsson has never taken a public stand on abortion.) Still, decades after they first appeared, Nilsson’s images endure for their unprecedentedly clear, detailed view of human life at its earliest stages.

The Pillow Fight, Harry Benson, 1964

Harry Benson didn’t want to meet the Beatles. The Glasgow-born photographer had plans to cover a news story in Africa when he was assigned to photograph the musicians in Paris. “I took myself for a serious journalist and I didn’t want to cover a rock ’n’ roll story,” he scoffed. But once he met the boys from Liverpool and heard them play, Benson had no desire to leave. “I thought, ‘God, I’m on the right story.’ ” The Beatles were on the cusp of greatness, and Benson was in the middle of it. His pillow-fight photo, taken in the swanky George V Hotel the night the band found out “I Want to Hold Your Hand” hit No. 1 in the U.S., freezes John, Paul, George and Ringo in an exuberant cascade of boyish talent—and perhaps their last moment of unbridled innocence. It captures the sheer joy, happiness and optimism that would be embraced as Beatlemania and that helped lift America’s morale just 11 weeks after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The following month, Benson accompanied the Fab Four as they flew to New York City to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, kick-starting the British Invasion. The trip led to decades of collaboration with the group and, as Benson later recalled, “I was so close to not being there.”

The Face Of Aids, Therese Frare, 1990

David Kirby died surrounded by his family. But Therese Frare’s photograph of the 32-year-old man on his deathbed did more than just capture the heartbreaking moment. It humanized AIDS, the disease that killed Kirby, at a time when it was ravaging victims largely out of public view. Frare’s photograph, published in LIFE in 1990, showed how the widely misunderstood disease devastated more than just its victims. It would be another year before the red ribbon became a symbol of compassion and resilience, and three years before President Bill Clinton created a White House Office of National AIDS Policy. In 1992 the clothing company Benetton used a colorized version of Frare’s photograph in a series of provocative ads. Many magazines refused to run it, and a range of groups called for a boycott. But Kirby’s family consented to its use, believing that the ad helped raise critical awareness about AIDS at a moment when the disease was still uncontrolled and sufferers were lobbying the federal government to speed the development of new drugs. “We just felt it was time that people saw the truth about AIDS,” Kirby’s mother Kay said. Thanks to Frare’s image, they did.

First Cell-Phone Picture, Philippe Kahn, 1997

Boredom can be a powerful incentive. In 1997, Philippe Kahn was stuck in a Northern California maternity ward with nothing to do. The software entrepreneur had been shooed away by his wife while she birthed their daughter, Sophie. So Kahn, who had been tinkering with technologies that share images instantly, jerry-built a device that could send a photo of his newborn to friends and family—in real time. Like any invention, the setup was crude: a digital camera connected to his flip-top cell phone, synched by a few lines of code he’d written on his laptop in the hospital. But the effect has transformed the world: Kahn’s device captured his daughter’s first moments and transmitted them instantly to more than 2,000 people.

Kahn soon refined his ad hoc prototype, and in 2000 Sharp used his technology to release the first commercially available integrated camera phone, in Japan. The phones were introduced to the U.S. market a few years later and soon became ubiquitous. Kahn’s invention forever altered how we communicate, perceive and experience the world and laid the groundwork for smartphones and photo-sharing applications like Instagram and Snapchat. Phones are now used to send hundreds of millions of images around the world every day—including a fair number of baby pictures.

Raising A Flag Over The Reichstag, Yevgeny Khaldei, 1945

“This is what I was waiting for for 1,400 days,” the Ukrainian-born Yevgeny Khaldei said as he gazed at the ruins of Berlin on May 2, 1945. After four years of fighting and photographing across Eastern Europe, the Red Army soldier arrived in the heart of the Nazis’ homeland armed with his Leica III rangefinder and a massive Soviet flag that his uncle, a tailor, had fashioned for him from three red tablecloths. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide two days before, yet the war still raged as Khaldei made his way to the Reichstag. There he told three soldiers to join him, and they clambered up broken stairs onto the parliament building’s blood-soaked parapet. Gazing through his camera, Khaldei knew he had the shot he had hoped for: “I was euphoric.” In printing, Khaldei dramatized the image by intensifying the smoke and darkening the sky—even scratching out part of the negative—to craft a romanticized scene that was part reality, part artifice and all patriotism. Published in the Russian magazine Ogonek, the image became an instant propaganda icon. And no wonder. The flag jutting from the heart of the enemy exalted the nobility of communism, proclaimed the Soviets the new overlords and hinted that by lowering the curtain of war, Premier Joseph Stalin would soon hoist a cold new iron one across the land.

Behind Closed Doors, Donna Ferrato, 1982

There was nothing particularly special about Garth and Lisa or the violence that happened in the bathroom of their suburban New Jersey home one night in 1982. Enraged by a perceived slight, Garth beat his wife while she cowered in a corner. Such acts of intimate-partner violence are not uncommon, but they usually happen in private. This time another person was in the room, photographer Donna Ferrato.

Ferrato, who had come to know the couple through a photo project on wealthy swingers, knew that simply bearing witness wasn’t enough. Her shutter clicked again and again. Ferrato approached magazine editors to publish the images, but all refused. So Ferrato did, in her 1991 book Living With the Enemy. The landmark volume chronicled domestic-violence episodes and their aftermaths, including those of the pseudonymous Garth and Lisa. Their real names are Elisabeth and Bengt; his identity was revealed for the first time as part of this project. Ferrato captured incidents and victims while living inside women’s shelters and shadowing police. Her work helped bring violence against women out of the shadows and forced policymakers to confront the issue. In 1994, Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act, increasing penalties against offenders and helping train police to treat it as a serious crime. Thanks to Ferrato, a private tragedy became a public cause.

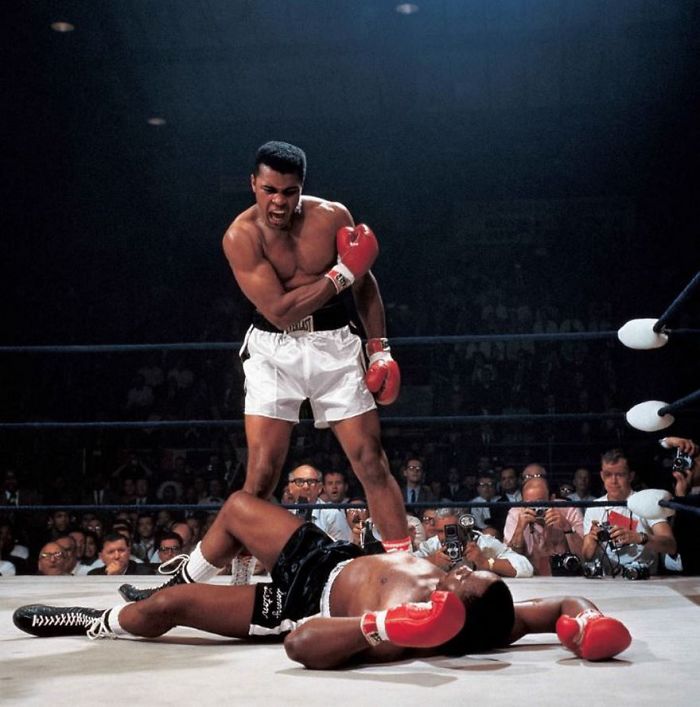

Muhammad Ali Vs. Sonny Liston, Neil Leifer, 1965

So much of great photography is being in the right spot at the right moment. That was what it was like for sports illustrated photographer Neil Leifer when he shot perhaps the greatest sports photo of the century. “I was obviously in the right seat, but what matters is I didn’t miss,” he later said. Leifer had taken that ringside spot in Lewiston, Maine, on May 25, 1965, as 23-year-old heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali squared off against 34-year-old Sonny Liston, the man he’d snatched the title from the previous year. One minute and 44 seconds into the first round, Ali’s right fist connected with Liston’s chin and Liston went down. Leifer snapped the photo of the champ towering over his vanquished opponent and taunting him, “Get up and fight, sucker!” Powerful overhead lights and thick clouds of cigar smoke had turned the ring into the perfect studio, and Leifer took full advantage. His perfectly composed image captures Ali radiating the strength and poetic brashness that made him the nation’s most beloved and reviled athlete, at a moment when sports, politics and popular culture were being squarely battered in the tumult of the ’60s.

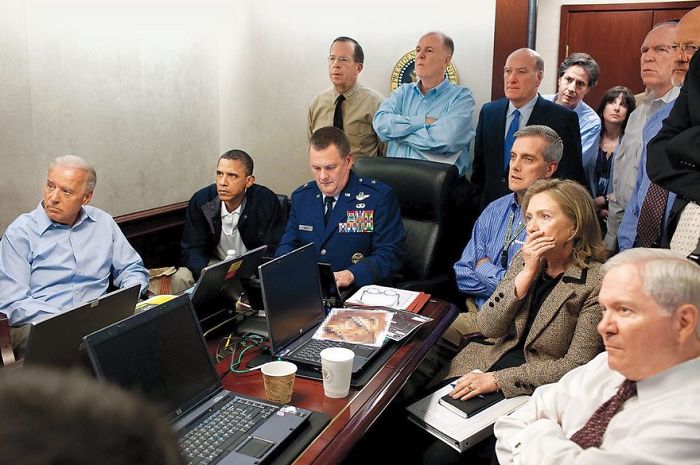

The Situation Room, Pete Souza, 2011

Official White House photographers document Presidents at play and at work, on the phone with world leaders and presiding over Oval Office meetings. But sometimes the unique access allows them to capture watershed moments that become our collective memory. On May 1, 2011, Pete Souza was inside the Situation Room as U.S. forces raided Osama bin Laden’s Pakistan compound and killed the terrorist leader. Yet Souza’s picture includes neither the raid nor bin Laden. Instead he captured those watching the secret operation in real time. President Barack Obama made the decision to launch the attack, but like everyone else in the room, he is a mere spectator to its execution. He stares, brow furrowed, at the raid unfolding on monitors. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton covers her mouth, waiting to see its outcome.

In a national address that evening from the White House, Obama announced that bin Laden had been killed. Photographs of the dead body have never been released, leaving Souza’s photo and the tension it captured as the only public image of the moment the war on terror notched its most important victory.

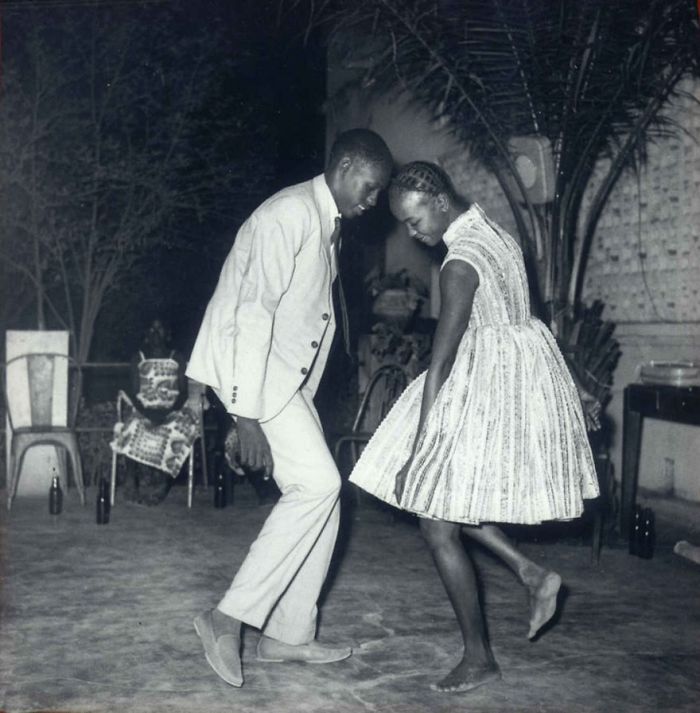

Nuit De Noel, Malick Sidibe, 1963

Malian photographer Malick Sidibé’s life followed the trajectory of his nation. He started out herding his family’s goats, then trained in jewelry making, painting and photography. As French colonial rule ended in 1960, he captured the subtle and profound changes reshaping his nation. Nicknamed the Eye of Bamako, Sidibé took thousands of photos that became a real-time chronicle of the euphoric zeitgeist gripping the capital, a document of a fleeting moment. “Everyone had to have the latest Paris style,” he observed of young people wearing flashy clothes, straddling Vespas and nuzzling in public as they embraced a world without shackles. On Christmas Eve in 1963, Sidibé happened on a young couple at a club, lost in each other’s eyes. What Sidibé called his “talent to observe” allowed him to capture their quiet intimacy, heads brushing as they grace an empty dance floor. “We were entering a new era, and people wanted to dance,” Sidibé said. “Music freed us. Suddenly, young men could get close to young women, hold them in their hands. Before, it was not allowed. And everyone wanted to be photographed dancing up close.”

Black Power Salute, John Dominis, 1968

The Olympics are intended to be a celebration of global unity. But when the American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos ascended the medal stand at the 1968 Games in Mexico City, they were determined to shatter the illusion that all was right in the world. Just before “The Star-Spangled Banner” began to play, Smith, the gold medalist, and Carlos, the bronze winner, bowed their heads and raised black-gloved fists in the air. Their message could not have been clearer: Before we salute America, America must treat blacks as equal. “We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat,” Carlos later said. John Dominis, a quick-fingered life photographer known for capturing unexpected moments, shot a close-up that revealed another layer: Smith in black socks, his running shoes off, in a gesture meant to symbolize black poverty. Published in life, Dominis’ image turned the somber protest into an iconic emblem of the turbulent 1960s.

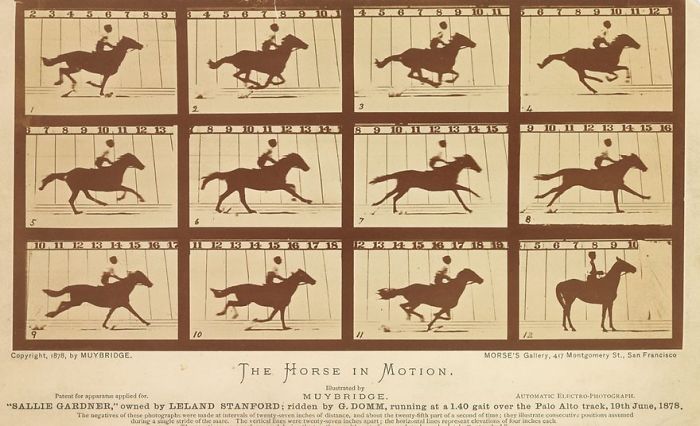

The Horse In Motion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1878

When a horse trots or gallops, does it ever become fully airborne? This was the question photographer Eadweard Muybridge set out to answer in 1878. Railroad tycoon and former California governor Leland Stanford was convinced the answer was yes and commissioned Muybridge to provide proof. Muybridge developed a way to take photos with an exposure lasting a fraction of a second and, with reporters as witnesses, arranged 12 cameras along a track on Stanford’s estate.

As a horse sped by, it tripped wires connected to the cameras, which took 12 photos in rapid succession. Muybridge developed the images on site and, in the frames, revealed that a horse is completely aloft with its hooves tucked underneath it for a brief moment during a stride. The revelation, imperceptible to the naked eye but apparent through photography, marked a new purpose for the medium. It could capture truth through technology. Muybridge’s stop-motion technique was an early form of animation that helped pave the way for the motion-picture industry, born a short decade later.

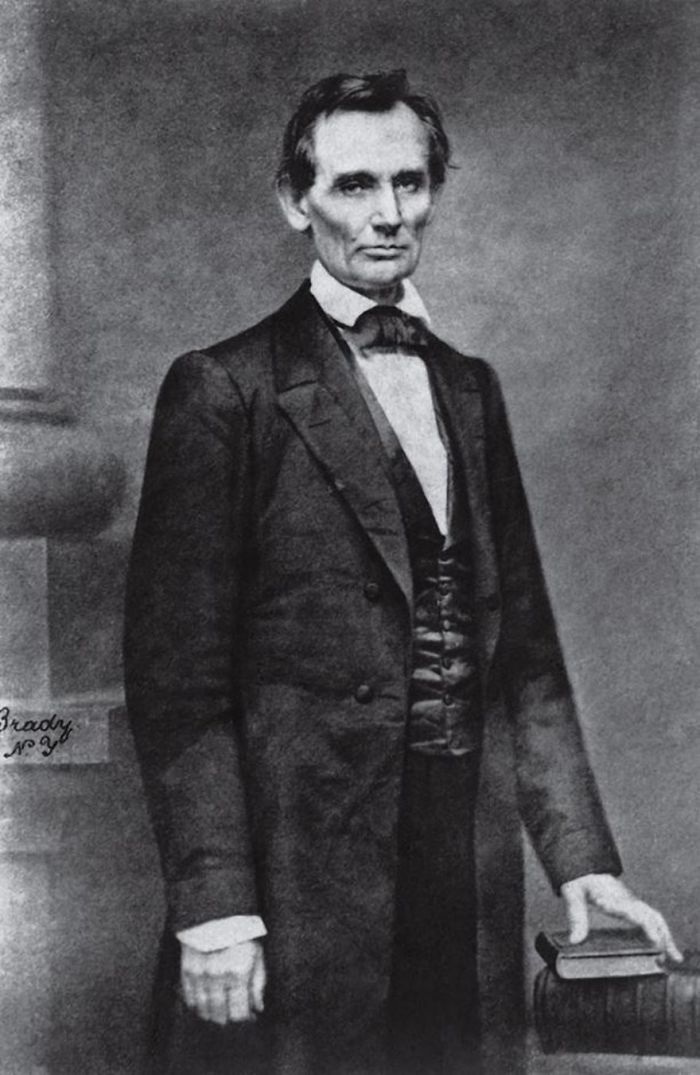

Abraham Lincoln, Mathew Brady, 1860

Abraham Lincoln was a little-known one-term Illinois Congressman with national aspirations when he arrived in New York City in February 1860 to speak at the Cooper Union. The speech had to be perfect, but Lincoln also knew the importance of image. Before taking to the podium, he stopped at the Broadway photography studio of Mathew B. Brady. The portraitist, who had photographed everyone from Edgar Allan Poe to James Fenimore Cooper and would chronicle the coming Civil War, knew a thing or two about presentation. He set the gangly rail splitter in a statesmanlike pose, tightened his shirt collar to hide his long neck and retouched the image to improve his looks. In a click of a shutter, Brady dispelled talk of what Lincoln said were “rumors of my long ungainly figure … making me into a man of human aspect and dignified bearing.” By capturing Lincoln’s youthful features before the ravages of the Civil War would etch his face with the strains of the Oval Office, Brady presented him as a calm contender in the fractious antebellum era. Lincoln’s subsequent talk before a largely Republican audience of 1,500 was a resounding success, and Brady’s picture soon appeared in publications like Harper’s Weekly and on cartes de visite and election posters and buttons, making it the most powerful early instance of a photo used as campaign propaganda. As the portrait spread, it propelled Lincoln from the edge of greatness to the White House, where he preserved the Union and ended slavery. As Lincoln later admitted, “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me President of the United States.”

Bandit's Roost, Mulberry Street, Jacob Riis, Circa 1888

Late 19th-century New York City was a magnet for the world’s immigrants, and the vast majority of them found not streets paved with gold but nearly subhuman squalor. While polite society turned a blind eye, brave reporters like the Danish-born Jacob Riis documented this shame of the Gilded Age. Riis did this by venturing into the city’s most ominous neighborhoods with his blinding magnesium flash powder lights, capturing the casual crime, grinding poverty and frightful overcrowding. Most famous of these was Riis’ image of a Lower East Side street gang, which conveys the danger that lurked around every bend. Such work became the basis of his revelatory book How the Other Half Lives, which forced Americans to confront what they had long ignored and galvanized reformers like the young New York politician Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote to the photographer, “I have read your book, and I have come to help.” Riis’ work was instrumental in bringing about New York State’s landmark Tenement House Act of 1901, which improved conditions for the poor. And his crusading approach and direct, confrontational style ushered in the age of documentary and muckraking photojournalism.

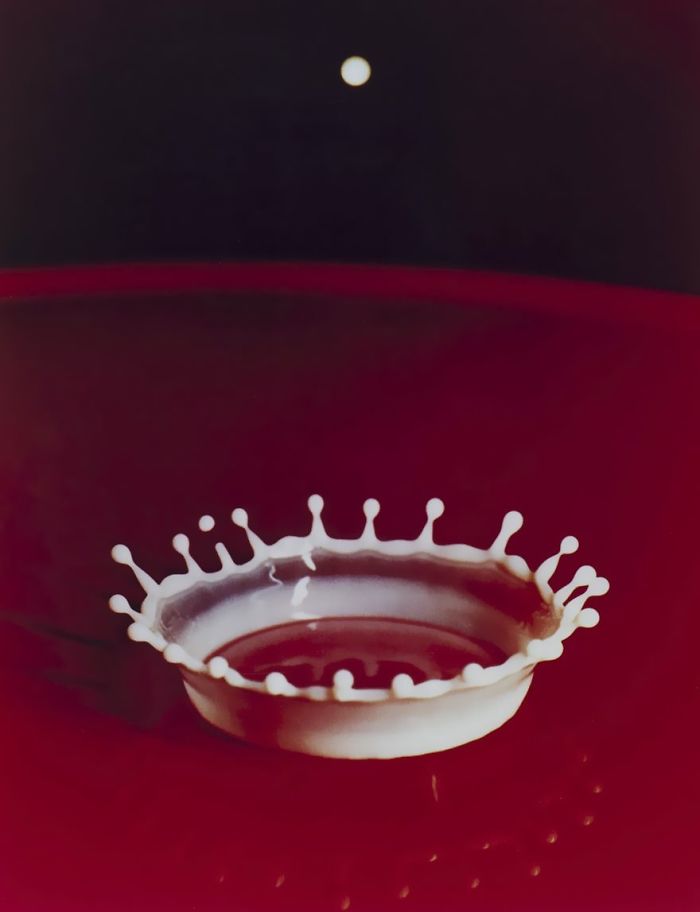

Milk Drop Coronet, Harold Edgerton, 1957

Before Harold Edgerton rigged a milk dropper next to a timer and a camera of his own invention, it was virtually impossible to take a good photo in the dark without bulky equipment. It was similarly futile to try to photograph a fleeting moment. But in the 1950s at his lab at MIT, Edgerton started tinkering with a process that would change the future of photography. There the electrical-engineering professor combined high-tech strobe lights with camera shutter motors to capture moments imperceptible to the naked eye. Milk Drop Coronet, his revolutionary stop-motion photograph, freezes the impact of a drop of milk on a table, a crown of liquid discernible to the camera for only a millisecond. The picture proved that photography could advance human understanding of the physical world, and the technology Edgerton used to take it laid the foundation for the modern electronic flash.

Edgerton worked for years to perfect his milk-drop photographs, many of which were black and white; one version was featured in the first photography exhibition at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, in 1937. And while the man known as Doc captured other blink-and-you-missed-it moments, like balloons bursting and a bullet piercing an apple, his milk drop remains a quintessential example of photography’s ability to make art out of evidence.

Surfing Hippos, Michael Nichols, 2000

Seven billion human beings take up a certain amount of space, which is one reason why wilderness—true, untouched wilderness—is fast dwindling around the world. Even in Africa, where lions and elephants still roam, the space for wild animals is shrinking. That’s what makes Michael Nichols’ photograph so special. Nichols and the National Geographic Society explorer Michael Fay undertook an arduous 2,000-mile trek from the Congo in central Africa to Gabon on the continent’s west coast. That was where Nichols captured a photograph of something astonishing—hippopotamuses swimming in the midnight blue Atlantic Ocean. It was an event few had seen before—while hippos spend most of their time in water, their habitat is more likely to be an inland river or swamp than the crashing sea.

The photograph itself is reliably beautiful, the eyes and snout of the hippo peeking just above the rippling ocean surface. But its effect was more than aesthetic. Gabon President Omar Bongo was inspired by Nichols’ pictures to create a system of national parks that now cover 11 percent of the country, ensuring that there will be at least some space left for the wild.

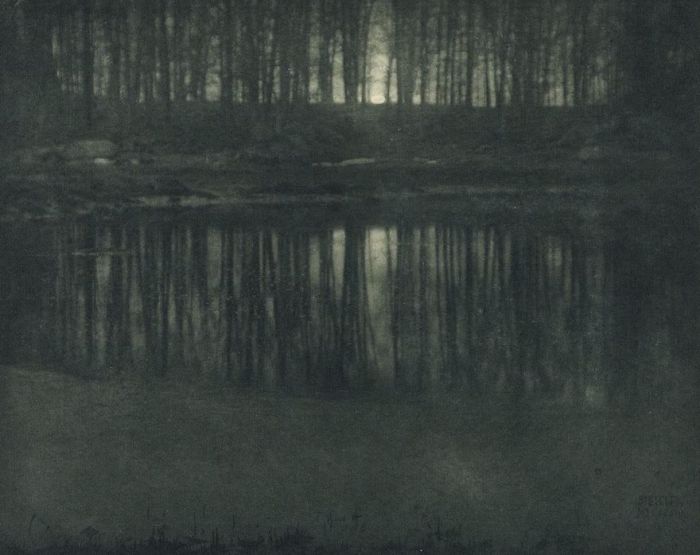

Moonlight: The Pond, Edward Steichen, 1904

Is Edward Steichen’s ethereal image a photograph or a painting? It’s both, and that was exactly his point. Steichen photographed the wooded scene in Mamaroneck, N.Y., hand-colored the black-and-white prints with blue tones and may have even added the glowing moon. The blurring of two mediums was the aim of Pictorialism, which was embraced by professional photographers at the turn of the 20th century as a way to differentiate their work from amateur snapshots taken with newly available handheld cameras. And no single image was more formative than Moonlight.

The year before he created Moonlight, Steichen wrote an essay arguing that altering photos was no different than choosing when and where to click the shutter. Photographers, he said, always have a perspective that necessarily distorts the authenticity of their images. Although Steichen eventually abandoned Pictorialism, the movement’s influence can be seen in every photographer who seeks to create scenes, not merely capture them. Moonlight, too, continues to resonate. A century after Steichen made the image, a print sold for nearly $3 million.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime