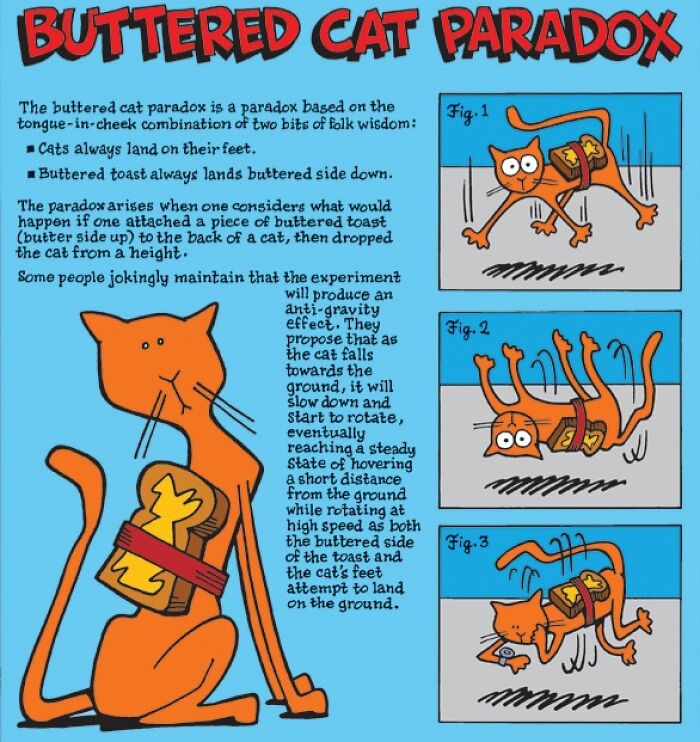

If cats always land on their feet and buttered toast always lands buttered side down, what would happen if you strapped buttered toast to the back of a cat - buttered side up - and it falls off a table?

It makes you think, doesn’t it? It’s a contradiction that might even confuse you. But some people refuse to believe that problems are unsolvable. And thus, there must be a concrete answer. So, if you were to ask certain scientists the question, they’d say the cat would never land. Instead, it would stop falling at some point above the floor. As it tries to orient its feet against the attraction of the butter to the floor, the cat would begin spinning - and it would never stop. Basically, buttered cat = perpetual motion machine. Problem solved. Or was it?

The Buttered Cat Paradox is one of many logical paradoxes. Confusing conundrums that contradict themselves. And seem to have no concrete solution. Until someone comes up with something that sort of makes sense, but also doesn't really. Bored Panda has put together a list of the best ones. Many of these mind-bending puzzles may make your brain hurt. So buckle up, keep scrolling and upvote the ones that turn your reality upside down.

This post may include affiliate links.

Abilene Paradox

The Abilene Paradox occurs when a group of people collectively agrees to a course of action that none of them individually want. This happens because each member mistakenly believes their own preferences are contrary to the group's desires, leading to a breakdown in communication. Consequently, individuals don't voice objections and may even express support for an outcome they secretly oppose, all while thinking they are aligning with the majority.

Feel you. But I work in it for a money(-grabbing) company so this is waaaaaaaaay more concerning

Load More Replies...A famous case was the lead-up to the Bay of Pigs invasion. The plan drafted by Richard Bissell under the Eisenhower/Nixon administration was deemed by many really bad and full of problems, and when the CIA director Dulles -who had the plan already greenlit by Eisenhower but had to have it executed by the next administration- presented it to the Kennedy White House, it went publicly uncommented. The incumbent President, the Defense, State and Treasury secretaries all expressed major concerns in private to their staff, but refrained from opposing it thinking the plan was surely sound since it was drafted by an experienced "coup-d'-etat" master, approved by a war hero president, and since no one else raised objections...

It is also a behavior that turned out in the Enron Scandal inquiry. A staggering number of employees had already noticed in advance the illegal accounting tricks and anomalies in the company, but did not discuss with their managers thinking the managers would for sure know best, and if something was off they would already know. Lack of whistleblowing channels meant that hundred of people who could have exposed the scandal way, way earlier convinced themselves to be in the wrong, and unwittingly played along.

Load More Replies...Not everything in life is meant to make sense. Or is it? The answer depends largely on who you ask. In the blue corner, those who are willing to not sweat the small stuff and let some sh*t slide. In the red corner, team "there must be a logical explanation for this utterly confusing contradiction."

Henry Dudeney once wrote: "A child asked, 'Can God do everything?' On receiving an affirmative reply, she at once said: 'Then can He make a stone so heavy that He can’t lift it?'"

Some would reply "yes." Others would say "no." A few might warn the child not to question faith.

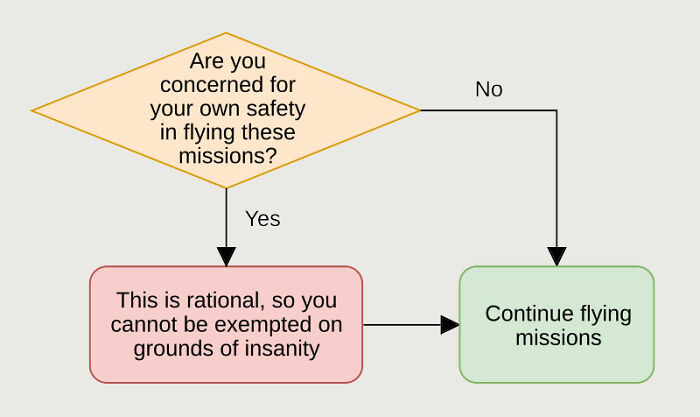

Catch-22

A Catch-22 describes a frustrating, no-win situation where you need something you can only get if you don't actually need it. For example, a soldier might want to be declared insane to get out of dangerous combat, but the very act of wanting to avoid combat is seen as a sign of sanity, meaning they won't be declared insane. It's a rule or situation that traps you in a loop.

Just keep doing finger guns at whoever’s speaking to you while raising your eyebrows periodically and otherwise remaining silent. Just to see what they do.

Sorites Paradox

The Sorites Paradox questions how we define vague terms like "heap." It points out that if you have a heap of sand and remove one grain, it's still a heap. If you continue removing grains one by one, eventually you won't have a heap. The paradox lies in the difficulty of identifying the exact point at which removing a single grain of sand transforms the heap into a non-heap.

If it rounds at the top, it is a heap, if it is flat, it is not. Source, every recipe that says heaping tsp.

So how many flying fücks can I take away before a fückton is no longer a fückton?

Imperial or metric fückton? Also, f***s should not be flying during weighing for obvious reasons.

Load More Replies...That's easy, Deutsches Institut für Normung. DIN These are literally the people who define what a Kilogram is and what the Meter is. If they can do that they must have an idea what a "heap" is.

Agree. This sounds more like a problem with unclear definitions rather than a paradox

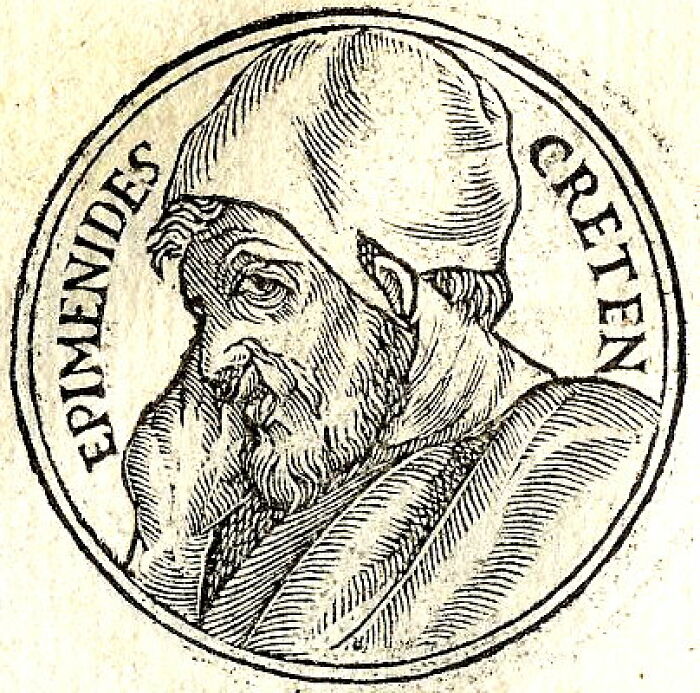

Load More Replies...If I told you "This sentence is a lie," would you believe me? It's the classic liar paradox, another contradictory statement that might get your head spinning. It's derived from something the Cretan prophet Epimenides said in the 6th century BCE: "All Cretans are liars."

"If Epimenides’ statement is taken to imply that all statements made by Cretans are false, then, since Epimenides was a Cretan, his statement is false (i.e., not all Cretans are liars)," explains Britannica.

If the sentence is true, then it is false, and if it is false, then it is true. Let that sink in, or swirl about, as you keep scrolling...

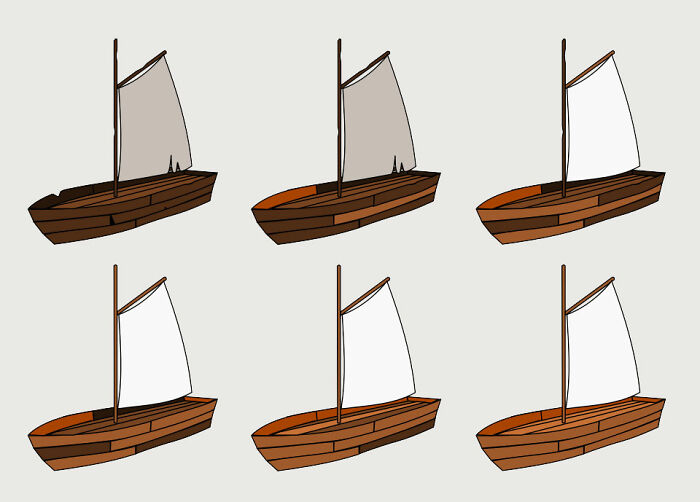

Ship Of Theseus

The Ship of Theseus paradox explores identity through change. If you replace every single component of a ship, one by one, is it still the original ship? This seems plausible. However, if you then take all the old, original pieces and reassemble them into a ship, that vessel also has a strong claim to being the original ship, creating a puzzle about which one, if either, truly is the same ship you started with.

Is the band Yes still Yes even though they have no original members? Steve Howe has a strong opinion on the matter.

So you referring to their first album as being the original YES or the next when Rick Wakeman joined them?

Load More Replies...Is Captain Kirk still Captain Kirk after being dissembled and reassembled by a transporter?

Our own bodies are continuously shedding cells. After a few years a complete cellular turnover has occurred. Is this still my body?

A ship is the memory, it is different for different people. As long as people associate the ship with their memory, to them it is the same ship.

If I take three identical machines apart and reassemble them with components sourced from a big bucket of randomized parts, are they the same machines? IMO, and I've done this a lot, there are bits and pieces that I remember. I used to have to do this a lot. Like more like 30 than 3 machines. But I would remember the dings and scratches and the quirks here and there.

Same with Henry VIIIs axe. Its had 6 new handles & 3 new heads but its still the same axe that cut his wives heads off.

It was originally The Ship of Theseus, now it’s The Ship Of Theseus Remastered.

I Know That I Know Nothing

The paradox "I know that I know nothing" famously associated with Socrates, encapsulates a profound philosophical stance. After the Oracle of Delphi declared him the wisest person, Socrates, deeply aware of his own lack of knowledge, concluded that his wisdom lay not in possessing knowledge, but in recognizing his own ignorance. This self-awareness differentiated him from others who mistakenly believed they knew things they did not.

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones. Rumsfeld

Well said, and by a man I thought would always be the worst Sec. Def. to come out of the Republican party. It is definitely the unknown unknowns that are worrying us now.

Load More Replies...A foolish man thinks himself to be wise. A wise man knows himself to be a fool.

There's nothing like studying for a degree to show you how little you know

Well how about that I believed that before I knew it was a paradox. Lol.

The opposite of Dunning-Kruger would be imposter syndrome - thinking you know, or are capable of, less than you actually do/are. I don’t sense that Socrates particularly felt like an imposter, more that his self-awareness of his own knowledge was far enough along the Dunning-Kruger curve to recognise how much there still is to possibly ‘know’, and the impossibility of ever knowing everything (plateau of sustainability).

Load More Replies...The Hedgehog's Dilemma is a logical paradox that actually might make sense to many of us. It's tells us that when hedgehogs or porcupines get too close to each other, they end up getting hurt or hurting each other. It's a metaphor for the human inability to break down all of one's inner walls towards others.

"A number of porcupines huddled together for warmth on a cold day in winter, but, as they began to prick one another with their quills, they were obliged to disperse. However, the cold drove them together again, when just the same thing happened. At last, after many turns of huddling and dispersing, they discovered that they would be best off by remaining at a little distance from one another," wrote philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer.

Paradox Of The Court

The Paradox of the Court presents a circular dilemma. A law student promises to pay his teacher only after winning his first case. When the teacher sues the student for payment (before the student has won any cases), a paradox emerges: if the teacher loses this lawsuit, the student has now won his first case (by virtue of the lawsuit concluding, even if he loses the payment demand) and thus must pay. However, if the student wins the lawsuit (meaning he doesn't have to pay based on this suit), he still hasn't won his "first case" according to the original agreement, and so shouldn't have to pay – yet winning this suit is his first win.

I feel like this could be a touching melodrama starring Kevin Bacon where the last plot twist is the teacher pays out anyway.

I see what you did there. Although I love Bacon and Sedgwick a bit toooo much.

Load More Replies...This isn't a paradox. If the teacher wins, the original agreement has been deemed invalid. If the student wins, he then has to pay, not based on the outcome of the lawsuit, but based on his agreement being deemed valid.

I think this explanation is written wrong... It gives two examples of the same outcome of the suit - one where teacher looses & one where student wins. It should be: If the teacher wins, student has to pay according to the ruling on the suit, but doesn't have to because he hasn't won his first case. If the student wins, he doesn't have to pay according to the ruling, but has to per agreement. It's also important that the agreement is about first case tried, not about first won. As in: I'll pay you IF I win the first case I'll be trying (proving the teacher is good). Not: I'll pay you WHEN I win for the first time.

The case wouldn't get to court in the first place since the deal was that they have to win their first case and they haven't had a case. Solved it.

This is why stupid people shouldn't write contracts. Anyone with sense would have covered that possibility in the contract.

If the student just hires a lawyer to represent him/her, and court decision is in favor of the student, then student still hasn't won a case as a lawyer. But if the student intends to be a practicing lawyer they might as well pay as soon as they have funds and get it over with. I find this an idiotic paradox with the example used.

It's not the paradox that's idiotic. Also, you don't need to be a lawyer to know that plaintiffs win cases every day.

Load More Replies...Schopenhauer adds that in the same way, humans come together seeking society, only to be mutually repelled by the many prickly and disagreeable qualities of their nature.

"The moderate distance which they at last discover to be the only tolerable condition of intercourse is the code of politeness and fine manners, and those who transgress it are roughly told—in the English phrase—to keep their distance," wrote the philosopher. "By this arrangement, the mutual need of warmth is only very moderately satisfied, but then people do not get pricked. A man who has some heat in himself prefers to remain outside, where he will neither prick other people nor get pricked himself."

Crocodile Dilemma

The Crocodile Dilemma describes a no-win situation: a crocodile steals a child and tells the parent it will return the child only if the parent correctly predicts whether the crocodile will return the child or not. If the parent predicts the crocodile will return the child, and the crocodile was going to do so, it keeps its word. But if the crocodile wasn't going to, it now must return the child to make the parent's prediction wrong, yet also not return it to keep its promise of only returning it on a correct prediction. Conversely, if the parent predicts the crocodile will not return the child, and the crocodile wasn't going to, it's a correct prediction, so the child should be returned, but this makes the prediction wrong. It creates a loop where the crocodile can't make a decision that aligns with its own rule.

Is no one planning to catch the talking crocodile? That thing would draw a crowd!

Jeez, just eat the child and stop playing with your food, Crocodile

Yeah, hang on, I don't think this one holds up. If the crocodile wasn't planning to return the child, and the parent predicted it would, then the parent is just wrong. There is no requirement for the crocodile to return the child 'to prove the parent's prediction wrong'. Therefore the sentence after that is also wrong (yet also not return it). This is only a paradox because it has been stated badly.

It's not a paradox if it's based on what the crocodile WAS going to do. The Croc can be like "I *WAS* going to eat the kid, which you predicted correctly, therefore I'll now return the kid." To be a paradox, it needs to relvole around what the crocodile DOES, not merely what it was PLANNING.

Hedgehog's Dilemma

The Hedgehog's Dilemma, sometimes called the porcupine dilemma, uses a metaphor to illustrate the challenges of human intimacy. It describes hedgehogs wanting to huddle together for warmth in cold weather, yet their sharp spines inevitably cause pain when they get too close. This illustrates how, despite a mutual desire for closeness and connection, the very act of getting close can lead to unavoidable hurt, forcing a difficult balance between connection and self-preservation.

Yet recent extensive researches By Darwin and Huxley and Ball Conclusively prove that the hedgehog Has never been buggered at all. Terry Pratchett RIP.

Hedgehogs, porcupines, and people are among a very small subset of mammals that primarily use the missionary position.

Load More Replies...The pain is not inevitable because hedgehogs can lay their spines flat so can huddle as close as they want. The problem only arises when one of them doesn't want the intimacy and raises its spines, so this isn't a paradox at all; it's a warning to be sure that the person you want to get close to actually wants you to be close to them.

The paradox arises when people think they are hedhogs and refuse to act like people.

Scrolling through this list of logical paradoxes brings one in particular to mind. It's attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates. And he said, “The only thing that I know, is that I know nothing.”

Taken literally, it would seem like a lie. Or a paradox. But it points to a deeper truth. We learn something new every day. We cannot possibly know everything. And challenging our thinking by seeking answers is an invaluable way to give our brains a good workout. Albeit sometimes a rather mind-bending one.

Intentionally Blank Page

The paradox of the "Intentionally Blank Page" occurs when a page in a document has the words "This page intentionally left blank" printed on it. The very presence of this text means the page is no longer truly blank, creating a direct contradiction with the statement itself.

I can relate to this as I think I've found a little paradox. Lets agree binary means 2. Lets say my friend identifies as non-binary. That implies that there must also be a binary. By declraring you are non binary you are by default putting yourself in a binary system. Not that it matters who you are I just find the terminology interesting.

I know I'm late to this, but the point of saying non-binary is that you disagree with the binary system that everyone else says exists. Acknowledging something is not the same as validating it. :)

Load More Replies...I'm wondering if the only people who think some of these are real paradoxes are the BP writers responsible fr the content. You mostly just find such pages in things like legal documents or other documents where it might be important to specifically point out that information wasn't omitted by accident.

Russell's Paradox

Russell's Paradox asks: does the set of all those sets that do not contain themselves as a member, actually contain itself? If this special set does contain itself, then by its own definition, it shouldn't (because it only contains sets that don't contain themselves). But if this special set doesn't contain itself, then by its own definition, it should (because it's a set that doesn't contain itself, and it's supposed to gather all such sets). This creates an inescapable contradiction.

This is a definite paradox. Either way they would cancel themselves out.

Godel the mathematician used that paradox (or a version of it) to prove that there is no mathematical system can prove itself this is his "incompleteness theorem) This a really dumbed down version of a wonderful mathematical proof

And an important theorem in science, art and music as well.

Load More Replies...I'm still stuck on the pizza, the tip, and where the extra dollar went. Black magick fuckery if you ask me.

Load More Replies...Raven Paradox

The Raven Paradox is the idea that observing a green apple actually increases the likelihood of all ravens being black. This seemingly odd conclusion comes from a rule of logic where the statement "All ravens are black" is considered logically the same as "All non-black things are non-ravens." Since a green apple is a non-black thing that is also a non-raven, observing it supports the second statement, and therefore, by strict logic, it also supports the first statement about ravens, even though it feels unrelated.

I just don’t get how seeing a random non-black object that’s not a raven reinforces the idea that ravens are black. I don’t get the relation.

Whoever wrote this did a poor job of it. It's more about using observation to support a false logic. The more non-black non-ravens the find the more they think it supports the idea that "All non-black things are non-ravens." But it's a logical fallacy with real implications - look, this person with autism had some vaccinations, therefore this supports the idea that vaccinations cause autism.

Load More Replies...The logic proposed is that ‘all ravens are black, therefore anything non-black cannot be a raven.’ So if you then see a green apple, it validates that statement by being a non-black (green) item, that is clearly not a raven. It’s misleading in that yes, seeing a green apple increases the validity of the statement, but seeing ANY non-black, non-raven item strengthens its validity. Until you see a non-black raven, you cannot prove the statement incorrect.

Therefore, given that leucistic (white) ravens exist, the statement is incorrect. Not all ravens are black so not all non-black things are non-ravens.

Load More Replies...I have Noone to discuss this with that would understand any of this.

https://www.fws.gov/story/white-raven-corvus-considered untitled-6...90d0d1.jpg

A rational person realizes that all non black things are not ravens does not mean all non ravens are not black.

Ah yes, statistics. They can be made to show anything you like, provided you choose your population accordingly.

Nope. This is not stats, this is simply a logical fallacy.

Load More Replies...Bhartrhari's Paradox

Bhartrhari's Paradox points out a tricky situation: if we say that some things can't be named, the very act of calling them "unnameable" actually gives them a name. This creates a direct conflict with the original idea that those things have no name.

A category is not a name. If I call you "person" I did not just use your name.

I agree! It would be better if ‘indescribable’ was used, since that IS a descriptor.

Load More Replies...This would never work in Germany. They have words for literally everything.

Unnameable is the same as calling it red or medium-sized: an adjective.

For instance, amongst the wizarding world, He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named is one very specific person.

Bt if there were five people who-must-not-be-named (douchey title by the way), then it refers to a category of people. Also, the vey title implies that there IS a name, it just should not be used for some reason.

Load More Replies...I've often thought of this for those who refuse to call the name of "God" by using G-d, Yahweh, or even "he who cannot be named". That is still giving them a name.

His name is spelled incorrectly. I can read the Sanskrit text in the illustration. It is Bradhari.

I checked on Google, it actually seems to correct. His name is spelled the same way in Hindi, as Bhartrihari, not Bradhari.

Load More Replies...Opposite Day

The Opposite Day paradox arises from the statement, "It is opposite day today." If this statement is true, then because it's opposite day, the statement must actually mean its opposite: "It is not opposite day today," which is a direct contradiction. On the other hand, if you assume the statement "It is opposite day today" is false, it would mean it's a normal day. On a normal day, that statement would simply be false, meaning it isn't opposite day, but this doesn't resolve the problem of trying to declare opposite day in the first place, as the declaration itself becomes self-refuting.

A word game is not the same thing as a paradox. One is a mere matter of semantics. The other actually concerns both concepts and physical reality.

Everyone knows that the statement of whether or not it's opposite day is exempt from the game. Basic rules, people.

So it can only be opposite day if A - you are told it is NOT opposite day. Or B - you are talking to a liar, then who knows.

Liar Paradox

The Liar Paradox, also known as the Epimenides paradox, emerges from self-referential statements such as "This sentence is false" or a person declaring "I am lying." A contradiction arises when attempting to assign a truth value: if the statement "This sentence is false" is true, then what it asserts (that it's false) must be correct, meaning it's actually false. Conversely, if you assume the statement is false, then its claim (that it's false) is incorrect, meaning it must be true, leading to another inescapable contradiction.

Knower Paradox

The Knower Paradox arises from a sentence that refers to itself, specifically one that states, "This sentence is not known." The problem is, if the sentence is true (meaning it really isn't known), then we've just established its truth, so we now know it, which makes the original statement false. But if the sentence is false (meaning it is known), then what it says about itself (that it's not known) is incorrect, leading back to a contradiction.

The sentence is a known, incorrect statement. Just because we know it exists, doesn't make it right.

That's the whole point - the sentence contains negative that makes it impossible. It doesn't work for the positive statement of "This sentence is known".

Load More Replies...no, what we know is that we do not know the sentence because the original sentence is not there. This is like saying scientists call the parts of space they know nothing about 'the great unknown' and then some super smart person coming along and saying since you named it and described it with words then we do know that it's unknown so stop looking because now we know. No.

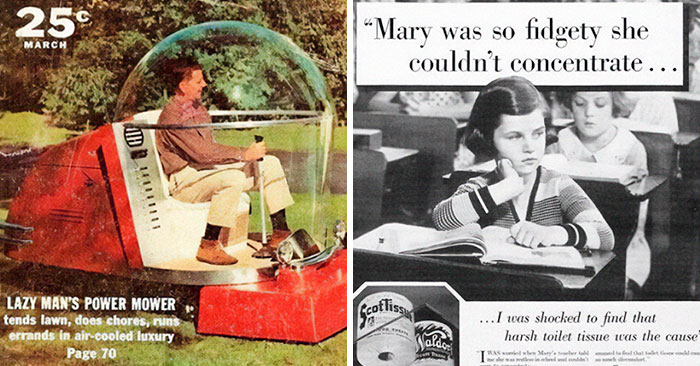

Buttered Cat Paradox

The Buttered Cat Paradox is a humorous thought experiment based on combining two common sayings: that cats always land on their feet, and that buttered toast always lands butter-side down. The paradox emerges when you imagine attaching a piece of buttered toast (with the buttered side facing up) to a cat's back and then dropping the cat. The two adages create a conflict, leading to a comical debate about how the cat would, or could, possibly land.

This is how UFOs work - they use a BCA (buttered cat array), attached within the disc of the craft. A small automated butter knife can both apply and remove butter allowing control of the strength of the effect. The associated yowlings combine to create the characteristic hum of the UFO.

Even if it were true that toast always lands buttered-side down, the simple fact is that a cat can control it's muscles to turn itself to the correct position. As the toast is passive (no control over it's fall) then the implication is that the uneven weight (buttered side being heavier) will cause the toast to turn in the air so the heavier side is facing downwards. The far greater mass of the cat along with its mobility will more than cancel out the slight weight imbalance caused by the butter.

Mythbusters sort of tested this. Butter side does not always fall down because duh. They built a machine to fling buttered toast off a table.

Drinker Paradox

The Drinker Paradox is a logic puzzle saying that in any pub, there's always one customer who makes this statement true: if that particular customer has a drink, then everyone in the pub has a drink. This seems odd, but it works out because if all customers are already drinking, then any drinking customer makes the statement true. If even one customer isn't drinking, then that non-drinking customer is the special one; since the "if they are drinking" part isn't true for them, the whole idea automatically holds up logically.

It's not the premise of the paradox, so can't be used to disprove it. But by the rules of logic, it still holds, just adds a bit of "history" before the paradox occurs: If two people are not drinking, then we know that not everyone in the pub is drinking. If one of them takes a drink, it's still true that not everyone is drinking. Only when both of them have a drink it becomes true that everyone in the pub is drinking.

Load More Replies...There are so many “if” statements in this that it’s absurdly illogical. It only works out if all customers are drinking, etc. Plenty of folks go to the pub for dinner!

Which is what many people thinks of philosophy in general. They are thought experiments, much like a brain in a vat, the Matrix, multiple realities, etc. Thank heavens Gene Roddenberry liked paradoxes and logic problems!

Load More Replies...Paradox Of Free Choice

The Paradox of Free Choice highlights a weird outcome when we use a basic logic rule with permissions. If you're told "You may have an apple," logic says it's also true to say "You may have an apple or you may have a pear." The problem is, this same logic could then imply "You may have an apple or you may fly to the moon," making it sound like you've been given permission for something totally random and unintended, just by adding an "or."

Very much so. But the poster described it poorly. This is, again, abstract logic. The speaker isn't saying you MAY have a pear, they are saying "It is either the case that you may have an apple, or it is the case that you may have a pear." Because you may have an apple, it doesn't matter if you may have a pear or not, the system returns true because one of the two conditions in the Or statement is true. Very important distinction in programming, completely useless everywhere else.

Load More Replies...If you're told "You may have an apple," logic says it's also true to say "You may have an apple or you may have a pear." - What? No it doesn't!

You may have an apple or you may be the Queen of England!

Load More Replies...This "paradox" is based on the phenomenon that in linguistics, an "or" can both be interpreted as a logical "OR" ("You can have an apple, or a pear, or both") and as a logical "XOR" ("You can either have an apple, or a pear, but not both"). Someone tried to brutalize this ambiguity into mathematical logic, resulting in a paradox where everything is allowed as long as there are two choices connected with an "or".

Well, no. If you come to my house and I offer you an apple, it's not a logical conclusion to think that I also have pears to offer.

This one is when you clash "common sense" logic with formal logic... What's true in common sense thinking, isn't always true in the science of logic. Adding "or" in formal logic totally changes the premises and equations. Stating "You may have an apple" does NOT follow that "you may have an apple or a pear/fly to the moon". Those would be completely different problems & equations.

I used examples of this to argue against Sartrean Existentialism. Free choice my asterix.

Barber Paradox

The Barber Paradox describes a situation with a male barber who shaves all men in town who do not shave themselves, and only those men. The question then arises: does the barber shave himself? If he does shave himself, he violates his rule of only shaving men who don't shave themselves. But if he doesn't shave himself, then according to his rule, he must shave himself, creating an unsolvable contradiction.

He is shaved by his wife, who is not a man, and tells him not to be ridiculous when he mentions the paradox. Then tells him to take out the trash.

The Barber Paradox IS Russell's Paradox, just formulated in a non-mathematical way.

the barber is actually a tiny, little monkey and therefore not a man. Solved

Just because he only shaves men who don’t shave themselves does not mean he shaves all men who do not shave themselves! So no, it is not the case that he must shave himself.

The problem clearly states he shaves "all men who do not shave themselves." Hilarious when internet peeps try to "solve" these paradox's, thereby completely missing the point. Is that a paradox?

Load More Replies...Grelling–Nelson Paradox

The Grelling–Nelson Paradox questions whether the word "heterological" (which means "not applicable to itself" or "does not describe itself") is, in fact, heterological. If "heterological" is heterological, then it doesn't apply to itself, meaning it's not heterological – a contradiction. Conversely, if "heterological" is not heterological (meaning it does apply to itself), then by its own definition, it should be heterological, leading to another contradiction.

Barbershop Paradox

The Barbershop Paradox explores the tricky consequences of believing that "if one of two simultaneous assumptions leads to a contradiction, the other assumption is also disproved." This very supposition—that proving one idea wrong automatically proves the other wrong when they're considered together—can itself lead to paradoxical or illogical outcomes.

I think originally it had something to do with which seat you sat in.

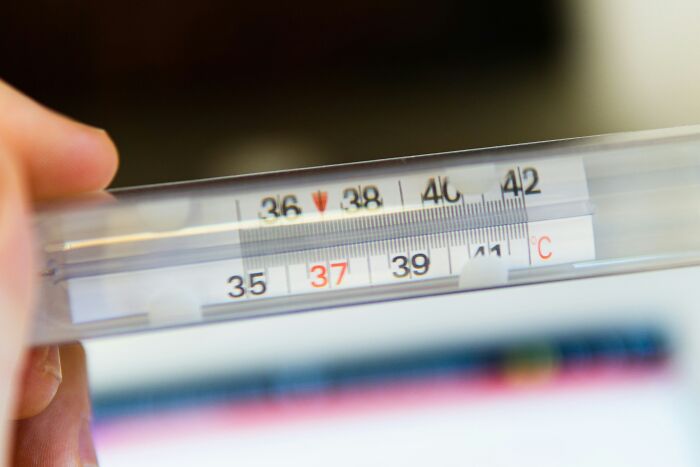

Load More Replies...Temperature Paradox

The Temperature Paradox, also known as Partee's paradox, highlights how language can be tricky. It presents an argument like this: "The temperature is ninety. The temperature is rising. Therefore, ninety is rising." The conclusion "ninety is rising" is clearly wrong. The paradox arises because the word "temperature" is used in two different ways: first, to state a specific value (ninety), and second, to describe a changing condition (rising). The number ninety itself cannot "rise" in the same way a temperature can.

Surprise Test Paradox

The Surprise Test Paradox explores a puzzle about expectations. Imagine a teacher tells students they will have a surprise test sometime next week, meaning they won't know which day it will be. Students might reason that if the test hasn't happened by Thursday, it must be Friday, so Friday wouldn't be a surprise. Ruling out Friday, they might then reason it can't be Thursday (as it would then be expected), and so on, seemingly eliminating all possible days. Yet, if the teacher gives the test on Wednesday, it still feels like a surprise, creating the paradox.

they can't rule out friday because it hasn't happened by Thursday before it hasn't happened by Thursday.

Berry Paradox

The Berry Paradox emerges from considering an expression like "The smallest positive integer not definable in under sixty letters." The problem is that this very phrase, which has fewer than sixty letters (for instance, fifty-seven letters), actually defines that specific integer. This creates a contradiction, because the phrase defines a number using fewer than sixty letters, while the number it's supposed to describe is one that allegedly cannot be defined in under sixty letters.

Lottery Paradox

The Lottery Paradox points out a conflict in what seems reasonable to believe. In a big lottery with only one winner, it makes sense to think that any single ticket you pick probably isn't the winner. However, it doesn't make sense to believe that none of the tickets will win, because we know there has to be one winning ticket.

I think that's when people don't play because they think they have no chance of winning at all. If everyone believes that, that includes the winner. But the winner can't win, since they didn't play, believing they could not win. (Or something like that)

Load More Replies...What The Tortoise Said To Achilles

This paradox, also known as Carroll's paradox, highlights a problem with the nature of logical deduction. It suggests that if you always need to add a new premise stating that a specific conclusion can be deduced from the existing premises, then you can never actually reach the conclusion, leading to an infinite regress. The core idea is that an inference rule (the method of reasoning) cannot simply be treated as another factual premise (something true or false) without running into this endless loop.

This isn't as big of a problem as it seems. Take the Big Bang for instance. The common argument is what was there before the big bang how did it come from nothing? The answer is that the Big Bang is the start of time. Matter and energy could always have existed, but time stood still. I guess what I am trying to say is infinite regression is applied many times when it shouldn't.

"This is my girlfriend." "I don't see any girls." "She's on my back. She's Michelle."

Load More Replies...This list uses a very loose definition of the word "paradox". Most are just word games or arbitrary rules. A true paradox is an impossible situation - like going back in time to k**l your own grandfather and thus making it so you were never born to go back in time to k**l your own grandfather. Word games and tricks of language are not true paradoxes.

Um... They might not seem like paradoxes to you because you would prefer to call them word games, but it doesn't change the fact that they exist (in mathematics, philosophy etc.).

Load More Replies...Although it's more of a thought experience, it is also kind of a paradox but Roko's Basilisk. "It’s like a future AI playing God, punishing people who didn’t help it become God—even if they lived before it existed. And the moment you hear about it, you’re caught in the trap… unless you choose to help."

Henry Dudeni should've realized that the Condescension already solved his paradox: That is, the universe was created in such a way that required Christ to become human. By doing so, he became unable to lift enormous boulders. But if you argue that he had had the ability to do so, but since the universe was created by Him to require the condescension, then the boulder could not fulfill the purpose for which he created it if he could throw it, so essentially, he couldn't throw it, but not because he's not almighty enough. If you argue that even as Christ, he had the ability to use miracles to lift the boulder, than his purpose for becoming Christ is impinged.

The only rule without an exception is "there's an exception to every rule."

This list uses a very loose definition of the word "paradox". Most are just word games or arbitrary rules. A true paradox is an impossible situation - like going back in time to k**l your own grandfather and thus making it so you were never born to go back in time to k**l your own grandfather. Word games and tricks of language are not true paradoxes.

Um... They might not seem like paradoxes to you because you would prefer to call them word games, but it doesn't change the fact that they exist (in mathematics, philosophy etc.).

Load More Replies...Although it's more of a thought experience, it is also kind of a paradox but Roko's Basilisk. "It’s like a future AI playing God, punishing people who didn’t help it become God—even if they lived before it existed. And the moment you hear about it, you’re caught in the trap… unless you choose to help."

Henry Dudeni should've realized that the Condescension already solved his paradox: That is, the universe was created in such a way that required Christ to become human. By doing so, he became unable to lift enormous boulders. But if you argue that he had had the ability to do so, but since the universe was created by Him to require the condescension, then the boulder could not fulfill the purpose for which he created it if he could throw it, so essentially, he couldn't throw it, but not because he's not almighty enough. If you argue that even as Christ, he had the ability to use miracles to lift the boulder, than his purpose for becoming Christ is impinged.

The only rule without an exception is "there's an exception to every rule."

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime