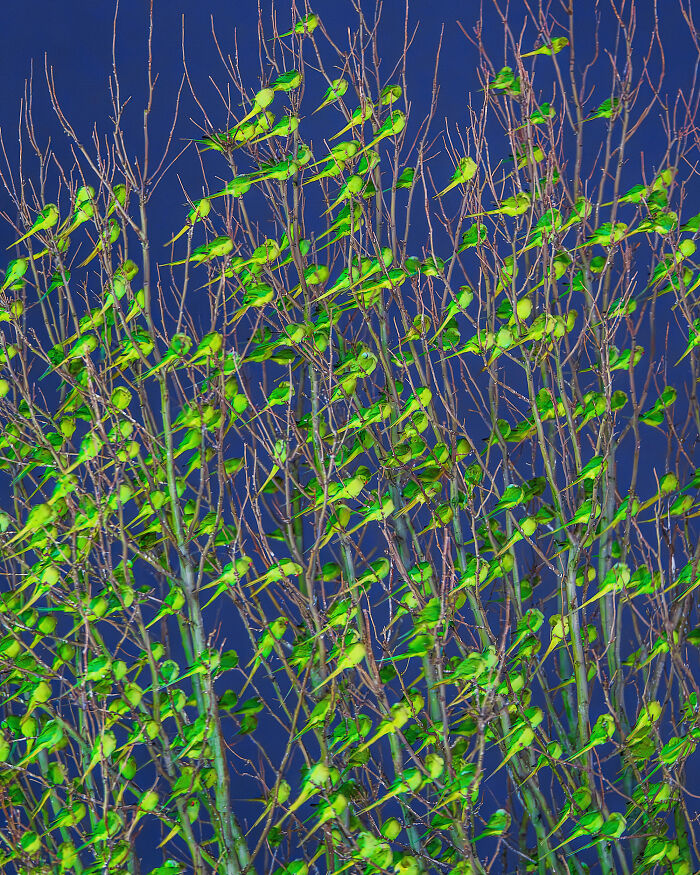

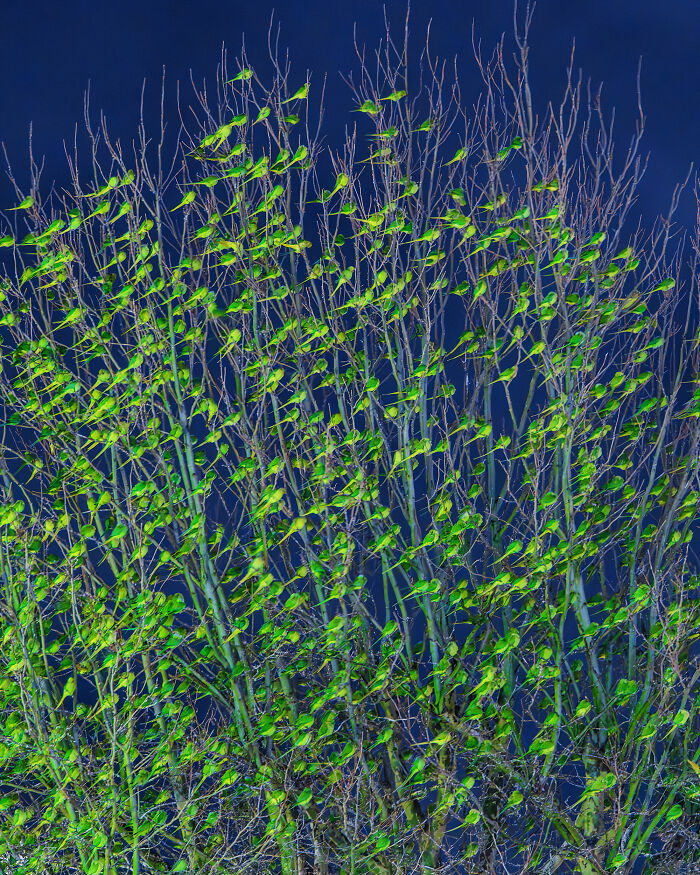

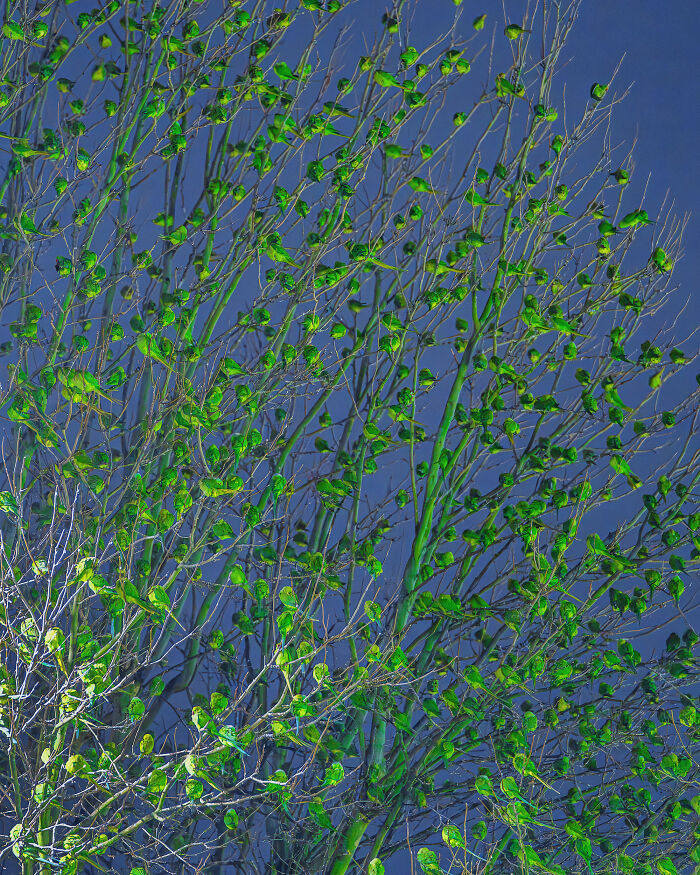

I Thought Winter Had Turned Green In London, Until I Realized It Was A Thousand Parakeets (35 Pics)

If you've never visited parks in London or other English cities, you’ve probably never experienced the surprise of seeing flocks of vibrant ring-necked parrots in migration. In spring, they nibble delicately on cherry blossoms, savoring the sweet nectar. While the sight is beautiful, it also means the cherry blossom season is shortened to just a single day.

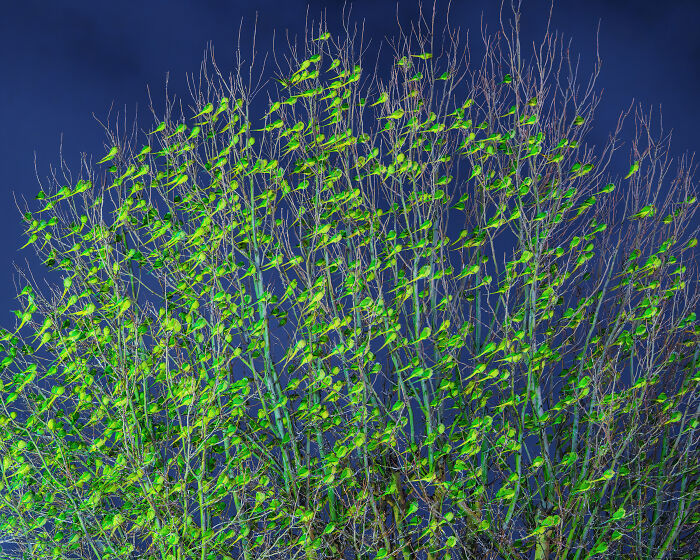

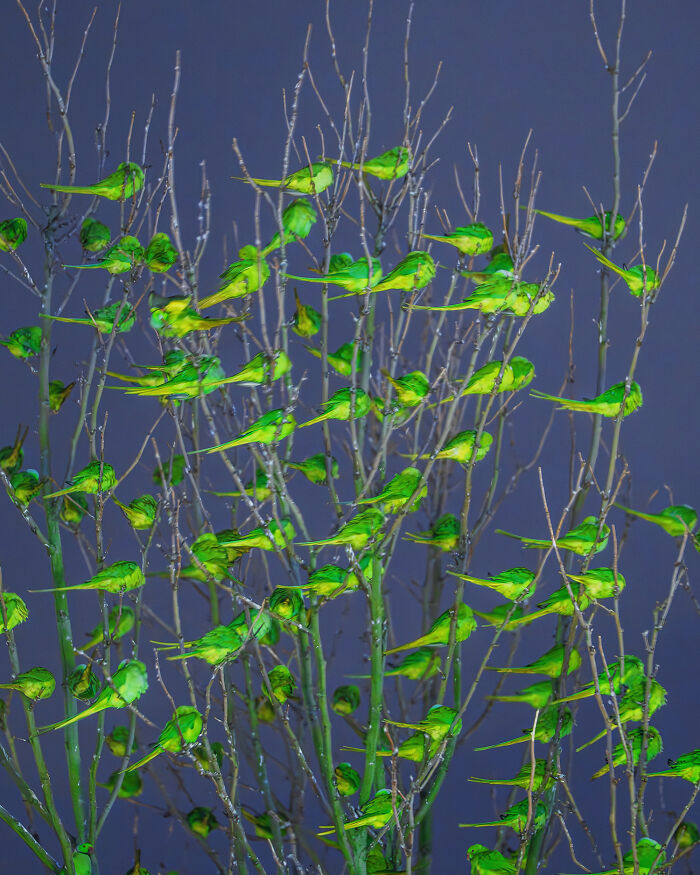

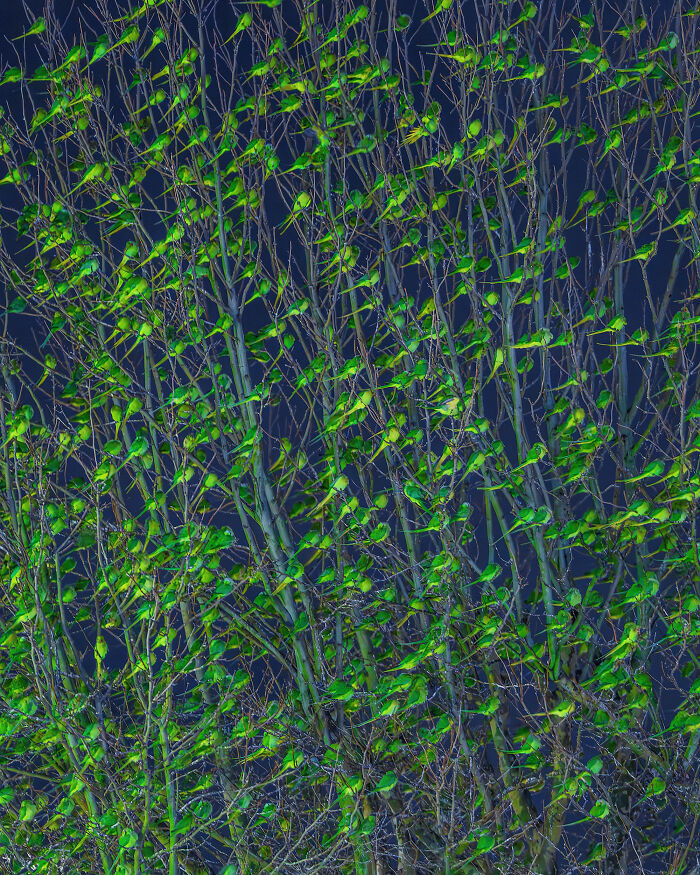

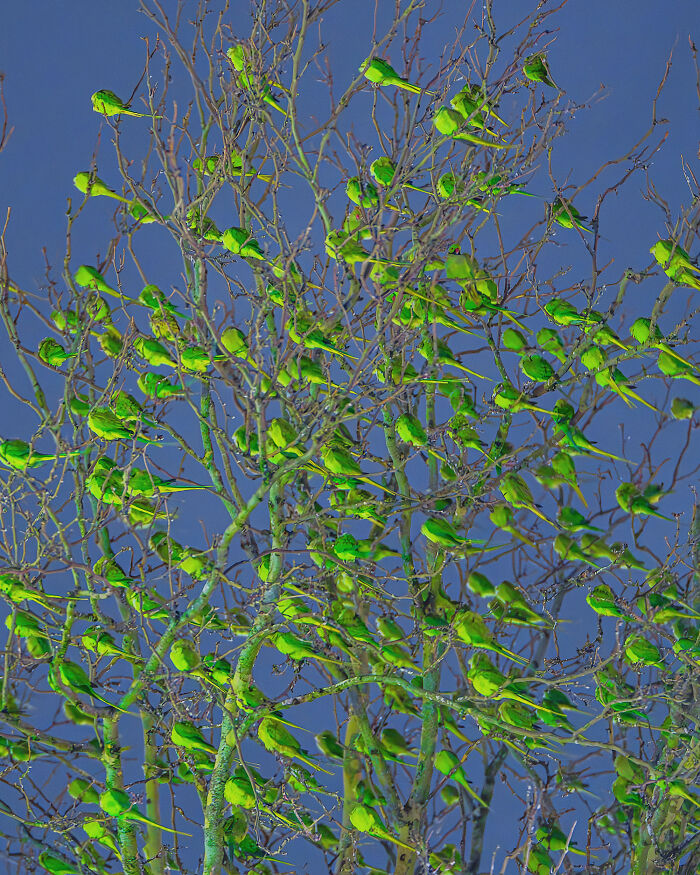

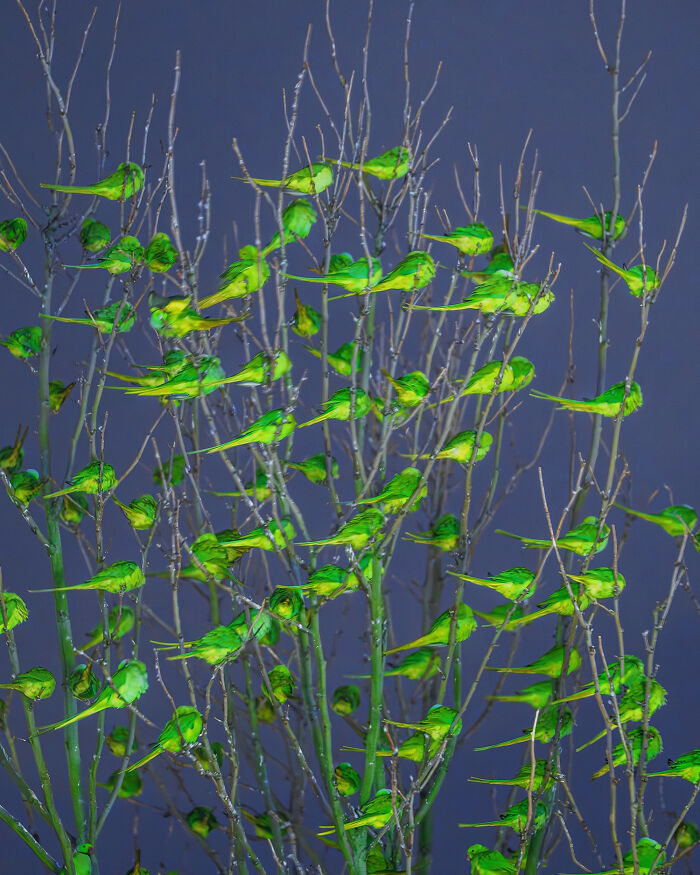

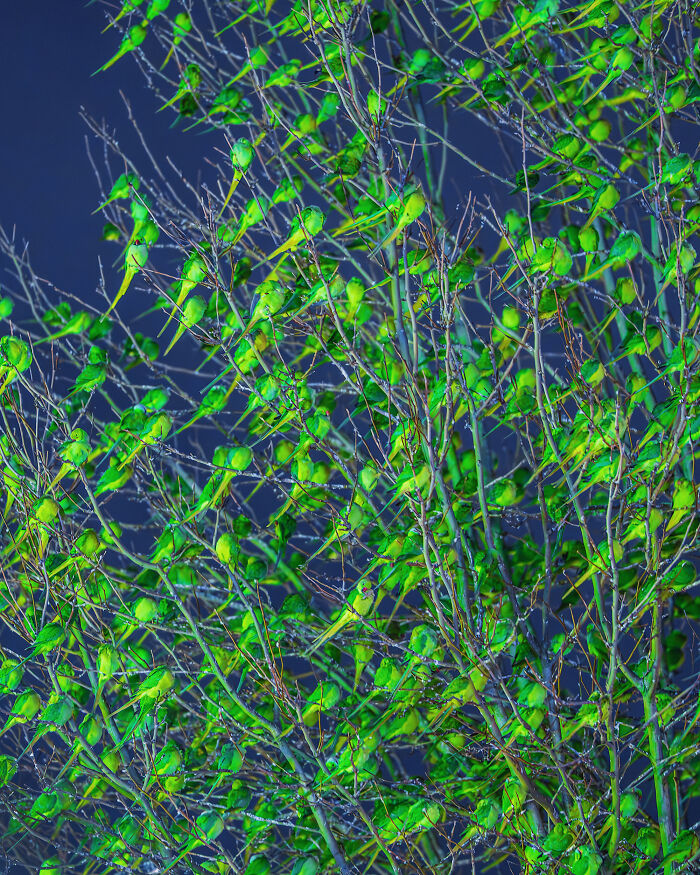

But I had never witnessed what I saw recently: hundreds of birds perched and sleeping in the trees around a car park. There were so many that the tree itself seemed to grow green leaves overnight.

More info: Instagram | hobopeeba.com | Facebook

This post may include affiliate links.

Of course, the moment captivated me, and I began taking photos. It was a stunning sight. Yet many British residents see it differently: they worry about how fast the birds multiply, how loud their squawking can be, and how aggressively they devour crops. They’re fearless—offer them an apple, and green parakeets will swoop down without hesitation, sometimes even fighting over it.

The origin of the parakeets remains officially unknown, but they are certainly not native to Britain. With their bright green plumage and the pink ring around their necks, it's hard to imagine a more unexpected breeding bird for this region.

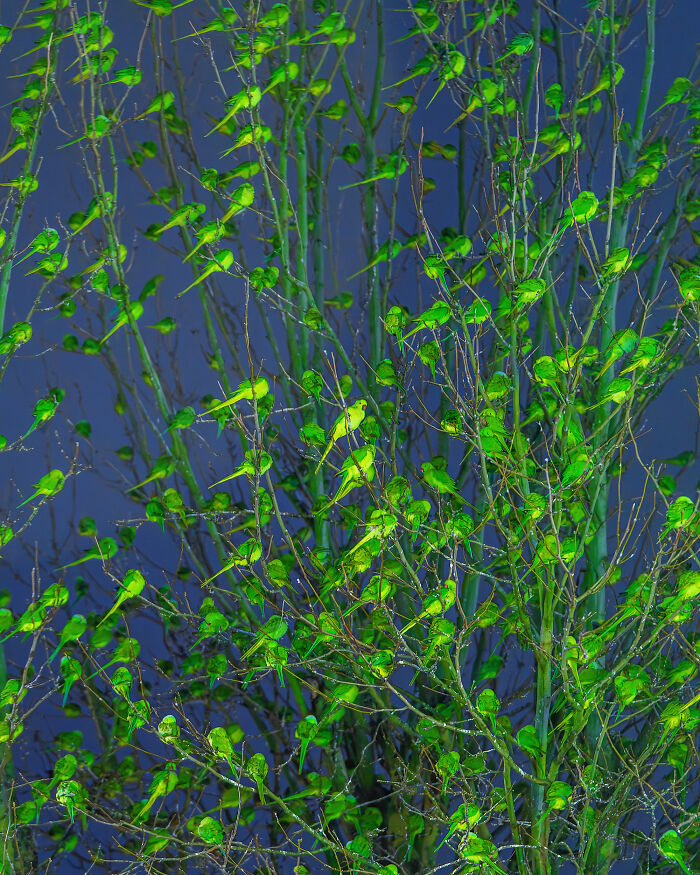

The first reports of parakeets in the wild in Britain date back to the 1860s. Recent data shows a sharp rise in their population, and experts warn of a “green invasion.” Ring-necked parakeets, native to India and Pakistan, are now classified as an invasive species. Since 1995, their numbers have increased by more than 2,000%. The population has not only doubled in the past decade but grown by nearly a third in just the last five years.

Added to the British Species List in 1983, the ring-necked parakeet has long been a popular cage bird. Today’s estimated 12,000 breeding pairs in Britain are the result of countless escapes from captivity over many decades. These birds now represent the northernmost breeding parrots in the world.

Their population, mainly concentrated in southeast England, frequently visits bird feeders, enjoying seeds, nuts, fruits, and fat pellets.

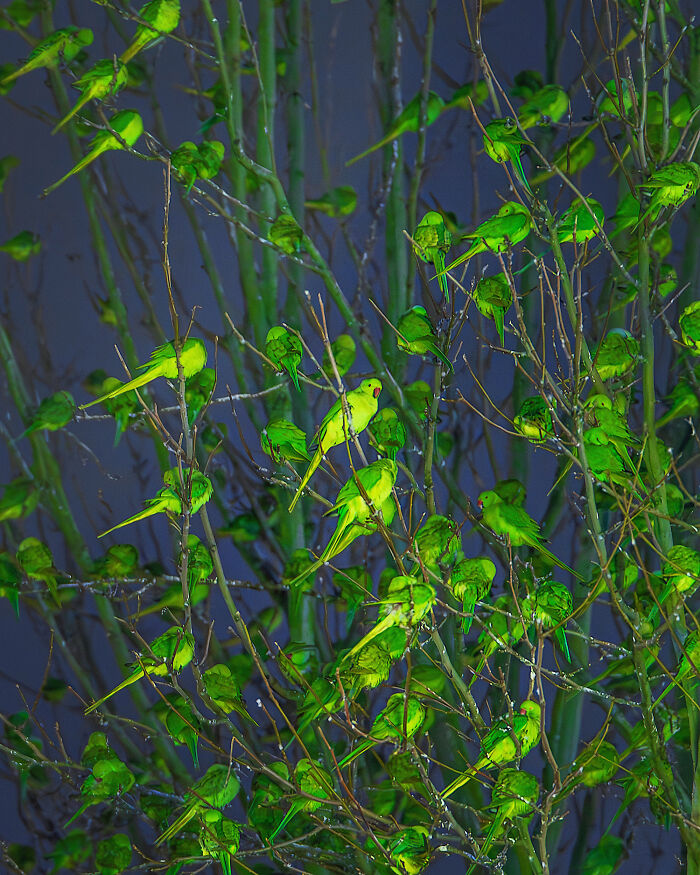

Winters in England are relatively mild—cool but rarely harsh. Night temperatures seldom drop below 0°C, and snowfall is limited to a few days each year. But for parrots accustomed to tropical climates, even these winters are significant. At first, they seemed to treat the cold as a temporary inconvenience. But when the snow arrived, they realized they needed to adapt. They began building colony nests—large shared structures for several birds. This strategy helped them survive the winter and even raise offspring.

Native birds like crows and jackdaws are slowly losing ground to the increasingly organized and dominant parakeets, whose feral population continues to expand.

Many people looking at the photos wonder why all the birds face the same direction. The reason is likely similar to why airplanes land facing into the wind: it gives them control. Facing the wind allows birds to slow their speed relative to the ground while maintaining enough lift in the air. When the wind is just right, they can even hover briefly before landing on a branch or wire—their movement almost still relative to the ground, yet full of energy relative to the air.

Useless information - Touched on some of this briefly in my comments above, but these are Indian Ringneck parrots/parakeets as they're referred to here (I'll refer to them as 'IRNs'). The mature males (they hit maturity around two) develop the famous 'ring' around their neck; the ladies and young 'uns don't have a ring. Males can get territorial - if you want IRNs as pets it's generally better to not go with two males (unless you've confirmed that they are compatible). Both males and females can talk but as with most birds, males are more likely to/likely to be more understandable. IRNs have this adorable squeaky voice when they talk. When they're bred in captivity, they come in different colours such as blue, yellow, etc.

Useless information - Touched on some of this briefly in my comments above, but these are Indian Ringneck parrots/parakeets as they're referred to here (I'll refer to them as 'IRNs'). The mature males (they hit maturity around two) develop the famous 'ring' around their neck; the ladies and young 'uns don't have a ring. Males can get territorial - if you want IRNs as pets it's generally better to not go with two males (unless you've confirmed that they are compatible). Both males and females can talk but as with most birds, males are more likely to/likely to be more understandable. IRNs have this adorable squeaky voice when they talk. When they're bred in captivity, they come in different colours such as blue, yellow, etc.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime