In an age when women were legally little more than property, a select few managed to amass fortunes that could rival kings and topple empires. They were the courtesans, a class of women who navigated the treacherous corridors of power not with a birthright, but with dazzling intellect, sharp ambition, and a masterful understanding of human desire. But this is not just a list of famous mistresses. It's a look at some of history's most brilliant entrepreneurs. They didn't just accept jewels; they directed national budgets, funded legendary artists, and built architectural marvels that stand to this day. From ancient Athens to revolutionary Paris, prepare to meet 31 women who refused to be powerless, proving that the savviest of investments was often in themselves.

This post may include affiliate links.

Madame Du Barry (28 August 1744 – 8 December 1793)

From the illegitimate daughter of a seamstress to a woman commanding an almost limitless fortune, Madame Du Barry's rise was nothing short of meteoric. Once installed as Louis XV's official mistress, her affection was rewarded with a torrent of gold from the royal treasury. She drenched herself in jewels, commissioned priceless art, and was gifted the lavish Château de Louveciennes. In an era when women held little power, she amassed a personal fortune so vast that its recovery, ironically, became the very reason she was arrested and ultimately led to the guillotine.

Jeanne De Valois-Saint-Remy (22 July 1756 – 23 August 1791

While her Valois name carried the weight of royalty, Jeanne's pockets were utterly empty but that was a fact she refused to accept. So, she decided to forge her own fortune, quite literally. Her target was nothing less than the most extravagant diamond necklace ever created, a treasure worth a modern fortune. By masterfully manipulating a cardinal, faking the Queen's signature, and playing on the court's greed, Jeanne orchestrated a legendary con. She didn't just steal a fortune; her audacious scam for riches ignited a scandal so immense it helped bankrupt the public's trust in the monarchy itself.

Grace Dalrymple Elliott (C. 1754 – 16 May 1823)

Grace Dalrymple Elliott played a dangerous double game, parlaying her liaisons with the highest echelons of British and French royalty into a substantial personal fortune. But she didn't just spend her wealth on the trappings of a courtesan. As the French Revolution spiraled into the Reign of Terror, she transformed her riches into risk capital, bankrolling a covert operation to smuggle condemned aristocrats to safety. For Grace, money wasn't merely for luxury; it was the ammunition she used to defy revolutionaries, bribe officials, and ultimately, purchase the one asset that mattered more than any jewel: her own survival.

Marie Duplessis (15 January 1824 – 3 February 1847)

Marie Duplessis transformed her life into a work of art, and she made sure it was an expensive one. Her famed love of camellias and sophisticated style weren't just personal quirks; they were calculated investments in an exclusive brand. The wealthiest men in Paris lined up to fund her lavish lifestyle, proving that her greatest talent was turning impeccable taste into cold, hard cash.

Madame De Pompadour (29 December 1721 – 15 April 1764)

Madame de Pompadour translated King Louis XV’s affection directly into immense financial might. She didn't just receive gifts; she convinced the king to let her direct the nation's cultural spending. Her approval could launch the entire Sèvres porcelain manufactory or finance new architectural styles, turning her personal taste into one of France’s most formidable assets and making her a de facto minister of culture with a virtually limitless budget.

Bianca Cappello (1548 – 20 October 1587)

Bianca Cappello executed one of history’s most stunning social and financial coups. She began as the mistress to Francesco I de' Medici, but she wasn't content with just jewels and private allowances. She leveraged her influence so masterfully that she secured the ultimate prize: marriage. This move transformed her from a kept woman into the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, giving her direct access not to a personal purse, but to the legendary, near-limitless wealth of the entire Medici dynasty.

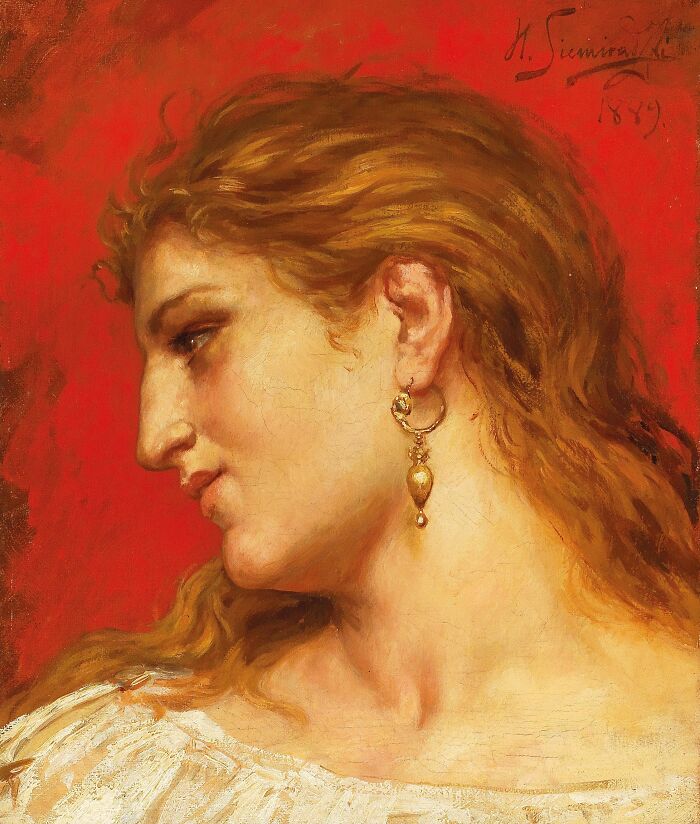

Aspasia (C. 470 – After 428 Bc)

As the brilliant foreign-born partner of Athens' great statesman, Pericles, Aspasia was legally denied the right to own land or claim citizenship. So she cultivated a more valuable currency: influence. Her salon became a legendary hub for the city’s sharpest minds, and her counsel was considered so essential that many whispered she was the intellectual force behind Pericles himself. She amassed a fortune not of coin, but of intellectual capital, making her one of the most powerful and respected women of the ancient world.

Phryne (Before 370 – After 316 Bc)

Phryne's fortune became so immense it was the stuff of legend. After Alexander the Great razed the city of Thebes, this celebrated Athenian hetaira made an astonishing offer: she would pay to rebuild the city's walls herself. Her one condition was that they be inscribed, "Destroyed by Alexander, restored by Phryne the courtesan." The offer alone was a flex of unimaginable financial power, proving that a woman who began with nothing could amass a personal treasury to rival that of kings.

Phryne modeled for the artists Apelles and Praxiteles: the Aphrodite of Knidos was said to be based on her. She is best known for her trial for impiety, in which she was defended by the orator Hypereides. According to legend, she was acquitted after her defender baring her breasts to the jury. Since that time no man could resist in front of a pair of beautiful teats.

Lais Of Corinth (Fl. 425 Bc)

Lais of Corinth didn't just entertain the elite; she set an entrance fee so steep it became a public measure of a man's own power and wealth. Philosophers like Aristippus and political giants like Demosthenes were counted among her clients, not just for her legendary beauty, but for the sheer prestige of being able to afford her. By turning her company into the ultimate luxury good, Lais commanded a fortune that made her one of the most famously affluent women in the entire Hellenic world.

Tullia D'aragona (1501/1505 – March Or April 1556)

For Tullia d'Aragona, the most valuable asset wasn't her beauty, but her brain (and she priced it accordingly.) In the competitive world of Renaissance Italy, she monetized her brilliance. Powerful patrons didn't just seek her company; they paid handsomely for the privilege of engaging with her sharp philosophical mind and hearing her acclaimed poetry. This financial independence allowed her to publish her work and debate with leading male thinkers on her own terms, effectively making her one of the few women of the era who could fund a career as a public intellectual through the very profession designed to objectify her.

Louise De La Valliere (6 August 1644 – 6 June 1710)

Even as the King’s affection waned, Louise de La Vallière’s financial future soared. When Madame de Montespan captured Louis XIV's eye, Louise wasn't simply dismissed; she was elevated. The King made her a Duchess in her own right and bestowed upon her vast, income-producing lands. It was the ultimate royal severance package, ensuring that while her place in the King’s bed was lost, her aristocratic power and immense personal fortune were guaranteed for life.

Cora Pearl (December 1836 – 8 July 1886)

Cora Pearl treated her body like a stage and her life as the ultimate performance, for which the ticket price was astronomical. This English import in Paris turned extravagance into an art form, dyeing her hair to match her carriage upholstery or famously bathing in a custom silver tub filled with champagne. She wasn't just acquiring riches; she was creating legendary, bank-breaking spectacles that the wealthiest men of the Second Empire were desperate to witness and willing to finance at any cost.

Liane De Pougy (2 July 1869 – 26 December 1950)

Liane de Pougy engaged in a legendary battle of opulence against her great rival, La Belle Otero. This wasn't just a competition of beauty; it was a financial arms race fought with cascades of diamonds and couture gowns, publicly funded by their powerful, smitten patrons. The result was an immense personal fortune, so vast that in her later years, she could afford the ultimate luxury: renouncing it all to live a simple, spiritual life as a Dominican tertiary.

Mata Hari (7 August 1876 – 15 October 1917)

Mata Hari built her fortune by selling the carefully crafted illusion of being a mysterious Javanese dancer to enraptured audiences and wealthy lovers across Europe. But during the Great War, the currency she allegedly dealt in became far more dangerous. The French government accused her of leveraging her intimate access to powerful officials to trade not in affection, but in state secrets for German gold. Whether she was a master spy or merely a convenient scapegoat, the price for her perceived transactions was the highest of all: her life.

Laure Hayman (12 June 1851 – 22 April 1940)

For Laure Hayman, becoming a courtesan was a calculated career move, a decision actively supported by her own mother. Her portfolio of patrons became a masterpiece of social strategy, boasting names like the Duc d'Orléans, the King of Greece, and even Marcel Proust's father. Each powerful liaison was a strategic investment, building a personal fortune that funded her true passions as a respected sculptor and influential salon host, placing her at the very center of Parisian cultural life.

Emilienne D'alencon (17 July 1870 – 14 February 1945)

This Parisian star essentially ran two profitable businesses at once. Her public career as a dancer and actress at venues like the Folies Bergère provided a steady, respectable income and built her celebrity brand. Privately, she leveraged that fame to attract a portfolio of wealthy patrons, including the powerful industrialist Etienne Balsan. She ultimately converted her success into long-term stability by marrying a successful jockey, proving she was as savvy in managing her assets as she was captivating on stage.

Virginia Oldoini, Countess Of Castiglione (23 March 1837 – 28 November 1899)

La Castiglione was a living diplomatic weapon, an Italian countess sent to Paris with one mission: to seduce Emperor Napoleon III. Her success was rewarded with access to the imperial treasury itself. But rather than simply amassing jewels, she channeled this staggering fortune into a groundbreaking and obsessive art project starring herself. She directed hundreds of elaborate photographs, spending a king's ransom on costumes and sets to control her own myth, making her not just a wealthy mistress but a pioneering artistic director of her own legend.

Lola Montez (17 February 1821 – 17 January 1861)

Lola Montez didn't just acquire a fortune; she leveraged her influence over King Ludwig I of Bavaria to claim one so vast it helped spark a revolution. Her rewards weren't mere jewels, but the official title of Countess, granting her immense wealth and unprecedented political power. When this influence ultimately toppled the government and forced her to flee, she proved her ultimate mastery of self-promotion by sailing to America and monetizing her own infamy, continuing to earn a living from the very scandal that had cost her a kingdom.

Veronica Franco (C. 1546–1591)

In Renaissance Venice, Veronica Franco transformed the courtesan's trade into a platform for public intellectualism. She brilliantly leveraged the income from her elite clientele to fund a career as a celebrated poet and author. This financial independence allowed her to publish works of feminist advocacy and pen letters advising the very patricians who were her patrons, effectively using her wealth to buy a voice and an autonomy that were otherwise impossible for women of her era.

Ninon De L'enclos (10 November 1620 – 17 October 1705)

Ninon de l'Enclos treated her earnings not as income, but as capital for a cultural enterprise. The fortunes she acquired from France's most powerful aristocrats were strategically reinvested. She acted as an angel investor for the arts, famously encouraging a young Molière and, in her will, bequeathing funds to a nine-year-old Voltaire specifically for the purchase of books. Her wealth wasn't just a measure of her desirability; it was the endowment for her legendary salon, turning her from a mere courtesan into one of history's most influential patrons.

Catherine Maria Fischer, (1 June 1741 – 10 March 1767)

Kitty Fisher was a true market innovator, recognizing that in an age of rising media, her own fame could be manufactured and sold like any other luxury good. She brilliantly weaponized portraits by renowned artists and scandalous newspaper mentions to build a personal brand of untouchable celebrity. Wealthy patrons didn't just pay for her company; they paid astronomical sums for a stake in her fame, making her one of the first people in history to convert sheer public fascination into a staggering personal fortune.

La Belle Otero (4 November 1868 – 10 April 1965)

La Belle Otero didn't just have lovers; she curated a collection of Europe's most powerful men. Her roster read like a global power index, including kings, tsars, and financiers, each vying for her attention. Every new affair was a high-stakes transaction, adding another legendary piece to a personal jewelry collection rumored to rival the crown jewels of entire nations. She effectively built a colossal fortune financed solely by the continent's absolute obsession with her.

Yang Guifei (719 – 15 July 756)

As the adored consort of Emperor Xuanzong, Yang Guifei's power over the imperial treasury was practically limitless. She didn't just enrich herself; she elevated her entire family to positions of immense power and staggering wealth. The Emperor lavished such fortunes upon her and her relatives that their corruption and influence became legendary, ultimately helping to destabilize the Tang dynasty itself.

Blanche D'antigny (9 May 1840 – 30 June 1874)

Émile Zola didn’t need to invent his famously destructive character, Nana; he simply had to observe Blanche d'Antigny. This notorious Second Empire courtesan lived the role in real life, cultivating a legendary and insatiable appetite for extravagance. Her talent for devouring the fortunes of her wealthy patrons was so spectacular it became the literal source material for one of literature’s most famous tales of ruinous desire.

Madame De Montespan (5 October 1640 – 27 May 1707)

For a glorious decade, Madame de Montespan wasn't just the King's mistress; she was France's unofficial queen, reigning from a lavish apartment at Versailles. She wielded her influence with absolute confidence, directing royal patronage and living in a state of unrivaled splendor. Her power was so complete that she achieved the ultimate financial victory: convincing Louis XIV to legitimize their seven children, transforming them into royalty and securing a dynastic fortune built entirely on her command of the king's heart.

Sophia Baddeley (1745 – July 1786)

Sophia Baddeley was a master at earning a fortune but a disaster at managing one. She seamlessly converted her theatrical fame into a high-stakes enterprise as a courtesan, where cash flowed in from powerful men like Viscount Melbourne. However, it flowed out just as quickly on a lifestyle of legendary extravagance. Ultimately, her inability to control her spending led to a complete financial implosion, forcing her to flee from her creditors, a celebrated star turned fugitive debtor.

La Paiva (7 May 1819 – 21 January 1884)

La Païva's ambition was literally set in stone. This Russian-born courtesan erected one of the most lavish mansions on the Champs-Élysées, the Hôtel de la Païva, as a monument to her own staggering success. Funded by a string of powerful patrons and solidified by her marriage to a fabulously wealthy count, the opulent home, with its legendary onyx staircase, was more than a residence; it was the ultimate trophy from a life spent mastering the art of the deal.

Sai Jinhua (Circa 1872-1936)

While other courtesans collected jewels, Sai Jinhua accumulated a far rarer asset: fluency in the languages and customs of the West. This unique portfolio paid off spectacularly during the Boxer Rebellion. When foreign armies occupied Beijing, her cross-cultural expertise made her a priceless intermediary, allegedly negotiating on behalf of the city's terrified populace. Her currency wasn't gold, but a strategic influence that, according to legend, placed her at the very center of a national crisis.

Volumnia Cytheris (Fl. 1st-Century Bc)

Beginning her life as human property, Volumnia Cytheris achieved a stunning reversal, becoming a symbol of ultimate luxury in Rome. Her true fortune wasn't counted in hidden coins, but in her shocking public visibility. When a man like Mark Antony paraded her at exclusive social events he wasn't just showing off a mistress. He was flaunting his immense power to shatter social norms, making Cytheris a living, breathing testament to his own untouchable status.

Gertrude Mahon (15 April 1752 – After 1807)

Dubbed the "Bird of Paradise," Gertrude Mahon brilliantly converted high fashion into high finance. She understood that every outrageous hat and scandalous dress was a calculated spectacle, designed to create a public frenzy. This strategy drove up demand for her company exponentially, ensuring her companionship was London's most talked-about and therefore most expensive luxury.

Su Xiaoxiao (C. 479 – C. 501)

While many courtesans of her time amassed fortunes in silk and jade, Su Xiaoxiao famously invested in a far more lasting asset: human potential. Legend holds that she used the considerable wealth earned from her admirers to fund the education of a promising but impoverished young scholar. This act of patronage cemented her legacy for centuries, proving that her greatest treasure was the ability to change lives for the better.

Amrapali (Around 500 Bc)

Amrapali’s price was so astronomical it was set by the state itself, making her the official "bride of the city." The immense fortune she accumulated from the republic's most powerful men allowed her to purchase prime assets, most notably a vast mango grove. Her ultimate power move, however, was not an acquisition but a donation. By gifting her entire grove to the Buddha and his order, she made a spiritual investment that cemented her legacy and demonstrated a wealth beyond the reach of mere kings.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime