37submissions

Finished

Twitter User Explains 37 Concepts Everyone Should Know To Understand The World Better

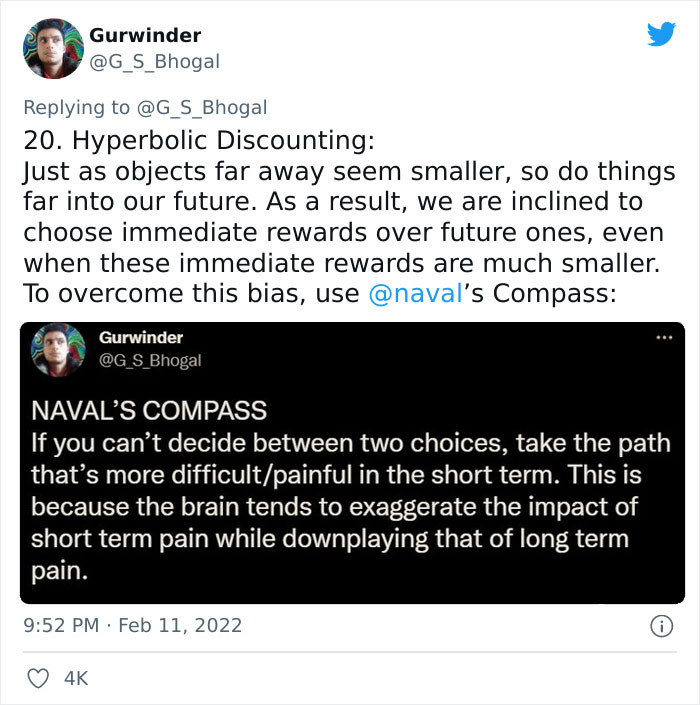

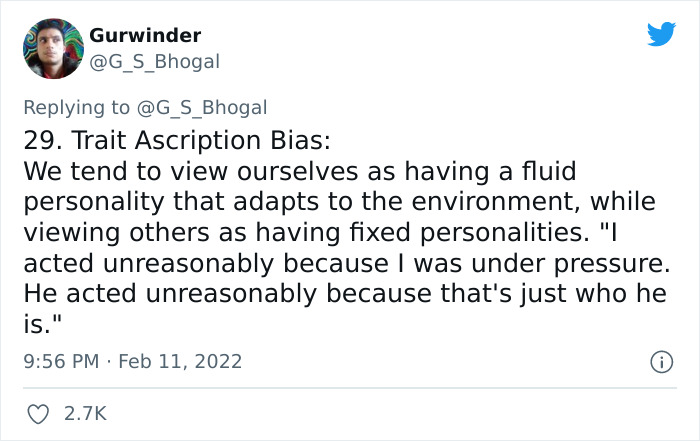

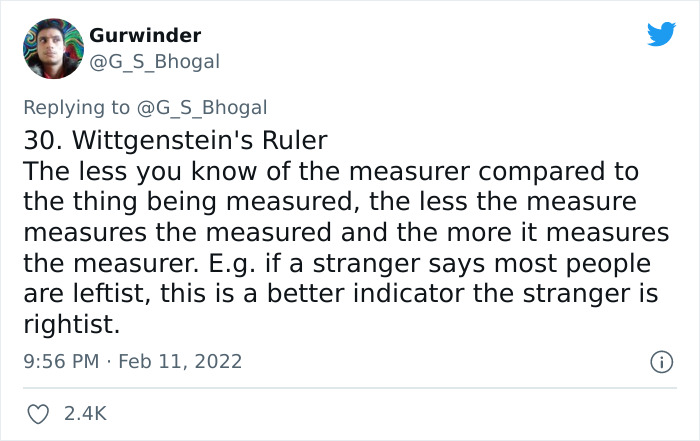

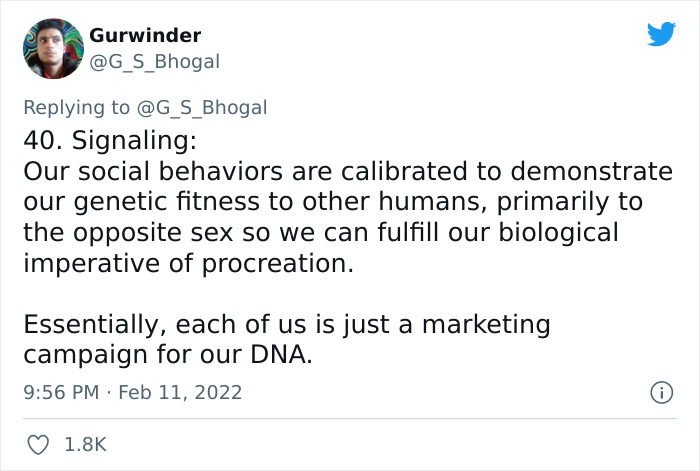

Twitter user Gurwinder regularly shares thoughts on various topics, including psychology, philosophy, and politics. However, one of their recent uploads offers all the above. And then some.

On February 11, Gurwinder posted a mega-thread, promising to broaden everyone's understanding of the world in just a few minutes.

In it, there are 40 concepts about human behavior and the world we live in. Scientists often spend years studying, researching, and analyzing complex phenomena but Gurwinder cuts to the very core of their findings and manages to explain everything in plain English.

Whether you decide to scroll through the entire thread or have time for only a couple of entries, I can assure you that it will be well worth it.

Discover more in Twitter User Explains 40 Concepts Everyone Should Know To Understand The World Better

Click here & follow us for more lists, facts, and stories.

This post may include affiliate links.

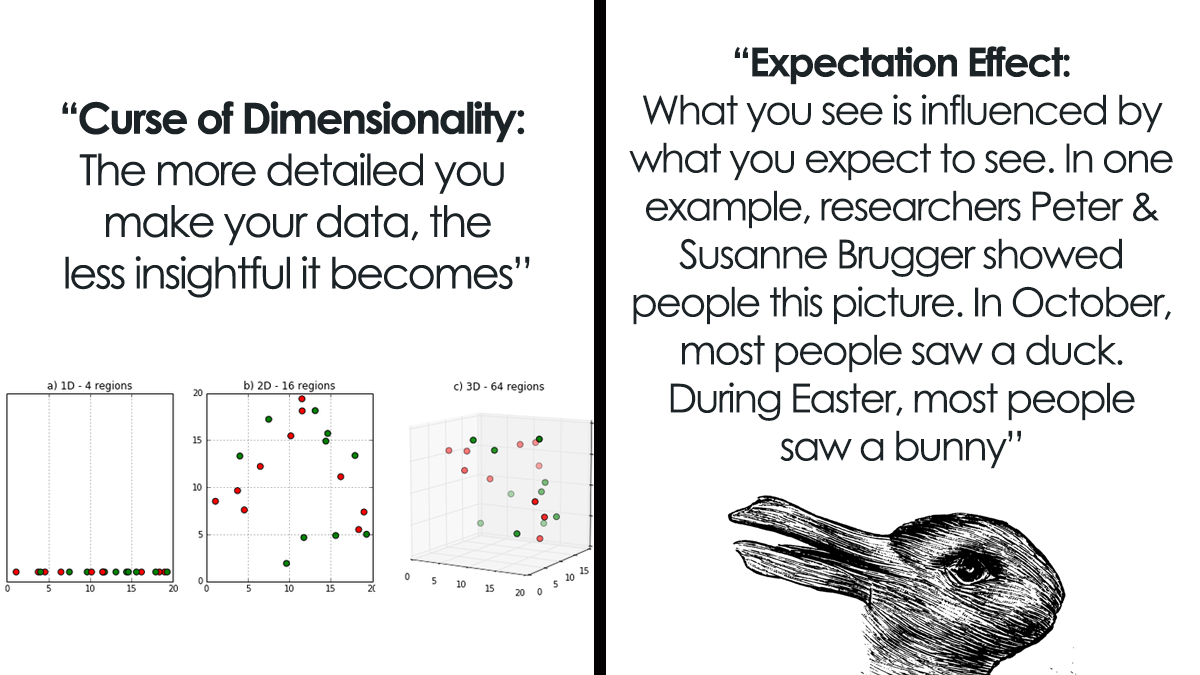

Such conclusions begin with a scientific method that allows us to collect measurable, empirical evidence in an experiment related to a hypothesis (often in the form of an if/then statement), designed to support or contradict a theory.

And that's really exciting. "As a field biologist, my favorite part of the scientific method is being in the field collecting the data," Jaime Tanner, a professor of biology at Marlboro College, told Live Science. "But what really makes that fun is knowing that you are trying to answer an interesting question. So the first step in identifying questions and generating possible answers (hypotheses) is also very important and is a creative process. Then once you collect the data, you analyze it to see if your hypothesis is supported or not."

According to Highline College, the steps of the scientific method are something like this:

- Make an observation or observations;

- Form a hypothesis — a tentative description of what's been observed, and make predictions based on that hypothesis;

- Test the hypothesis and predictions in an experiment that can be reproduced;

- Analyze the data and draw conclusions; accept or reject the hypothesis or modify the hypothesis if necessary;

- Reproduce the experiment until there are no discrepancies between observations and theory.

"Replication of methods and results is my favorite step in the scientific method," Moshe Pritsker, a former post-doctoral researcher at Harvard Medical School and CEO of JoVE, also told Live Science.

"The reproducibility of published experiments is the foundation of science. No reproducibility — no science."

The backbone of the scientific method is generating and testing a hypothesis. After an idea has been confirmed over many experiments, it can be called a scientific theory. While a theory explains a phenomenon, a scientific law provides a description of a phenomenon, according to The University of Waikato. Take the law of conservation of energy, for example. It is the first law of thermodynamics and says that energy can neither be created nor destroyed.

A law describes an observed phenomenon, but it doesn't explain why the phenomenon exists or what causes it. "In science, laws are a starting place," said Peter Coppinger, an associate professor of biology and biomedical engineering at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. "From there, scientists can then ask the questions, 'Why and how?'"

Laws are usually considered to be without exception, though some get modified over time if further testing finds discrepancies. For instance, Newton's laws of motion describe everything we've observed in the macroscopic world, but they break down at the subatomic level.

But this does not mean theories are meaningless. For a hypothesis to become a theory, scientists have to conduct rigorous testing, typically across multiple disciplines. Saying something is "just a theory" can be misleading as the scientific definition of "theory" and the layperson's understanding of it can be very different. To most people, a theory is a hunch but in science, it's the framework for observations and facts.

Probably all of us know someone who constantly questions and challenges everything they see and hear. No matter how much evidence is in front of them.

"The quality of cynicism, in its extreme, can be one component of the personality trait known as Machiavellianism," Susan Krauss Whitbourne, a professor emerita of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, wrote in Psychology Today. "You might already know what this quality is just by the term alone, but its formal definition includes not just a tendency to manipulate and exploit others, but also a deeply-held belief that others are, as the saying goes, 'out to get them.'"

"In research on the underlying motivation of the Machiavellian, TU Dorman University's Christian Blötner and Sebastian Bergold proposed that what they call 'avoidance' motivation leads these individuals to experience a deep sense of distrust and highly 'negative views of human nature," Whitbourne explained.

But not all cynics would qualify as people high on this overall trait of Machiavellianism. "It's possible that the very skeptical have simply developed a so-called 'cognitive style,' or analytical type of mindset that causes them to look at situations from all possible angles."

"Indeed, you might argue that some form of cynicism is adaptive," Whitbourne said. "Think about the highly gullible people you know who are easily swayed by whatever winds might be sweeping over the media landscape. Not only could they put themselves at risk for being swindled by the ads that fund the media landscape, but they can also be led to accept faulty information that puts their health and well-being in jeopardy. Maybe it is better to think twice or perhaps three times before rushing into such a poor decision."

In fact, knowing why some people believe in unsubstantiated claims and why misinformation guides their actions can be a valuable tool for resisting these traps. If you question loud phrases, you aren't automatically a cynic. Maybe you're just (a very healthy) skeptic.

- You Might Also Like: 45 Jokes And Memes That People Who Grew Up In The ’90s And 2000s Will Relate To

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime