These 3D Facial Reconstructions Reveal A More Human Mozart, Bach, And Beethoven

Painted portraits of famous figures reveal a lot about their likeness, with the mastery of artists being in their ability to capture someone’s essence. Yet, they lack the true three-dimensionality and plasticity of a face. And reconstructing these elements is exactly what keeps Brazilian 3D designer and researcher Cícero Moraes busy. You might remember him from Bored Panda’s previous feature on his reconstruction of Ivan the Terrible, where he used forensic-style methods and historical data to build a lifelike face from old remains and records.

Moraes has become a familiar name in the world where history, anatomy, and digital art overlap. His work focuses on facial approximation: creating a scientifically grounded “best possible” face from skeletal evidence, whether that’s a famous historical figure or human remains recovered in archaeological digs. It’s not the same thing as identification (DNA still wins that battle), but it can be surprisingly powerful for helping modern viewers connect with people who otherwise feel trapped behind oil paint and mythology.

More info: Instagram | ciceromoraes.com.br

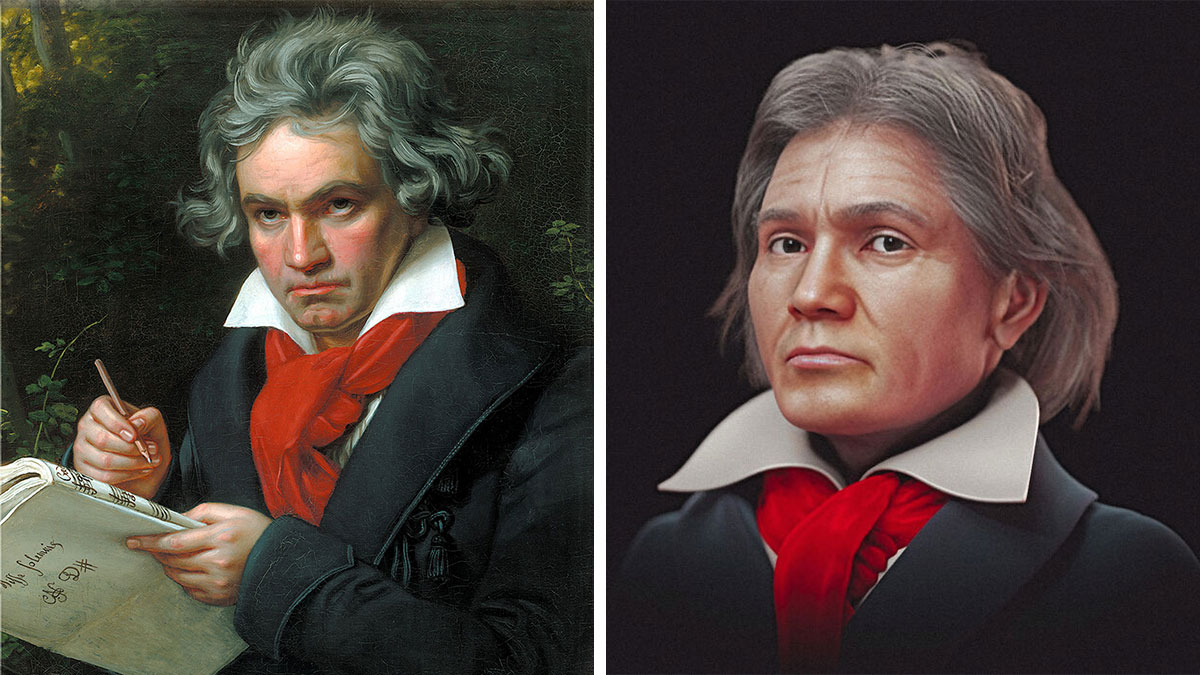

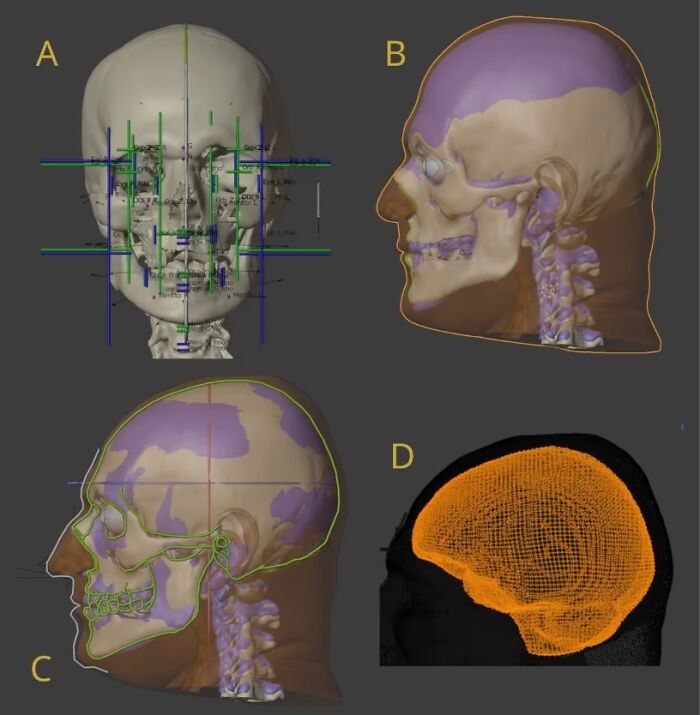

Beethoven’s skull, photographed straight-on, gives the hard limits for face width, jaw shape, and eye placement

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

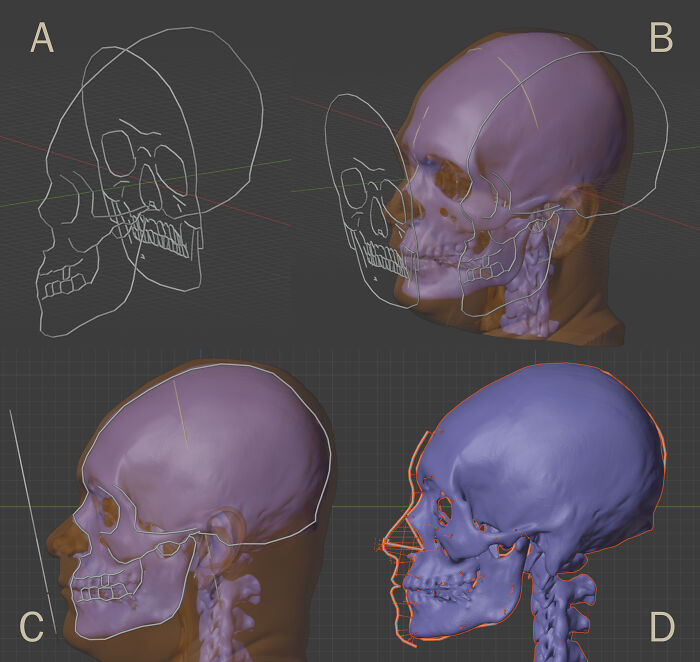

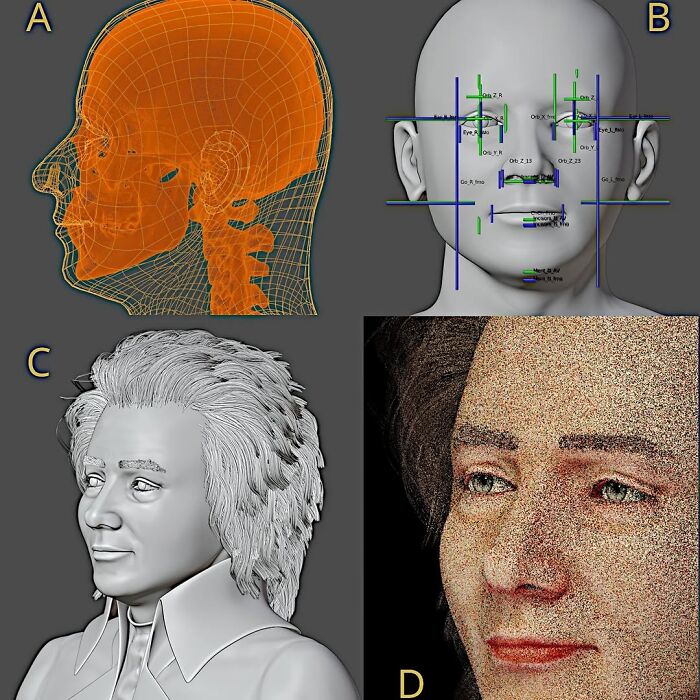

In this post, we’re staying in the world of classical music, bringing you facial reconstructions connected to Mozart, Bach, and Beethoven. And while each case can involve different source material (a skull, casts, old photos, or measurements), the underlying workflow follows a similar logic: start with the skull’s hard limits, then build outward using anatomical rules and population-based averages.

A side view makes the “profile math” obvious

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

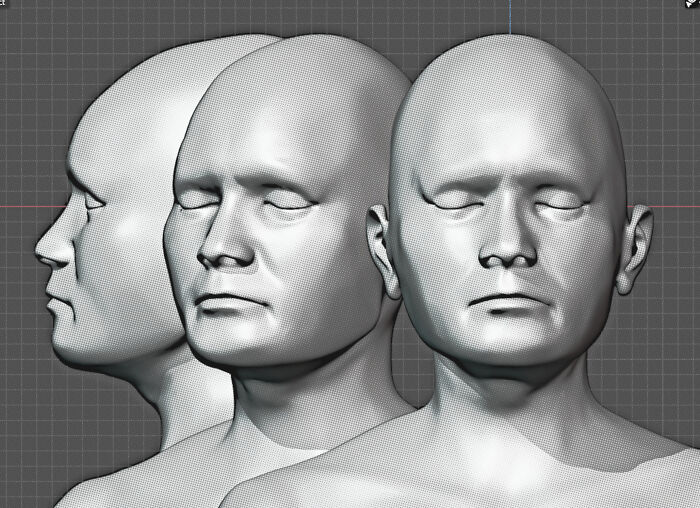

First glimpses of the face appear when the skull scan is uploaded into a 3D modelling program

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

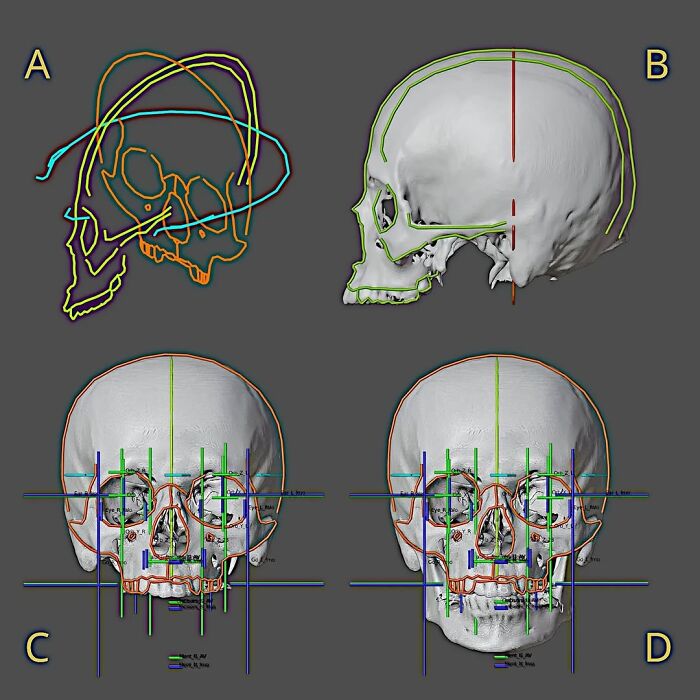

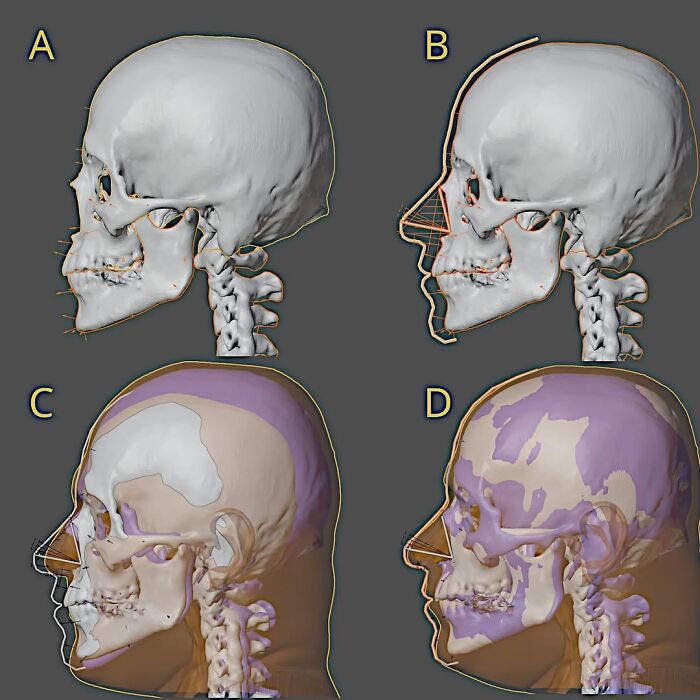

So what does that look like in practice? In Moraes’ digital workflow, the skull is first positioned and scaled in a 3D scene, sometimes reconstructed from published photos and measurements when a full scan isn’t available.

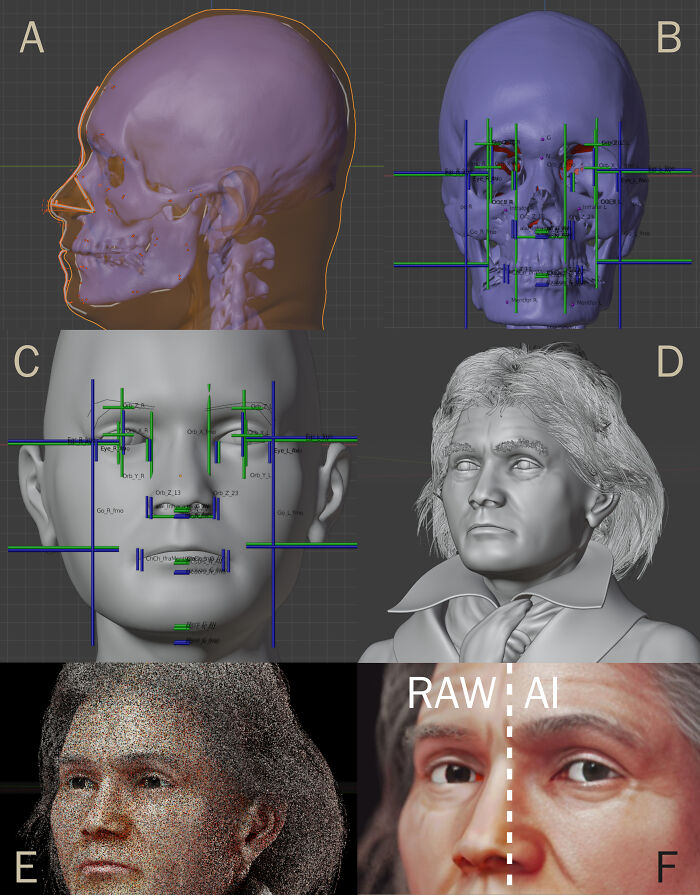

Before the face exists, Moraes builds the framework by overlaying reference guides to the skull

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

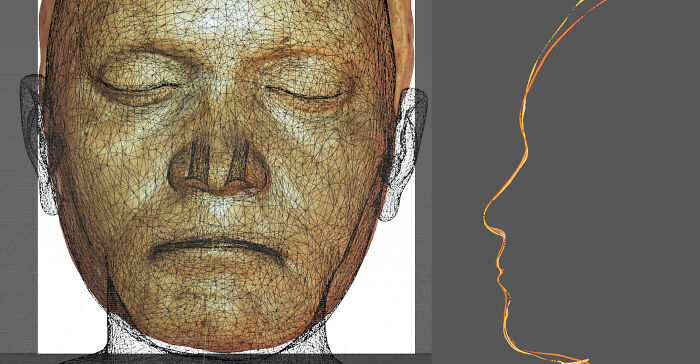

The skull gets “dressed” in a digital soft-tissue shell, showing how muscle and fat would sit over bone

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

From there, he adds soft-tissue thickness markers. These are depth guidelines based on real datasets across key points of the face to estimate how much “living” tissue would sit over bone. Next comes feature projection, especially the nose, which is notoriously tricky because cartilage doesn’t survive; to compensate, multiple established methods can be used together to estimate its likely shape.

Outlines and landmarks help compare multiple historical references

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

The skull is aligned with 2D reference geometry, letting Moraes test proportions and correct angle distortions

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

A particularly interesting step is using a “virtual donor” head scan (a CT-based reference) that’s digitally adjusted to match the target skull’s proportions, helping generate realistic facial volume before the final sculpting pass. Once the face is structurally complete, the more interpretive elements, hair, styling, and presentation, get layered in, and final detail can be enhanced with careful, human-supervised AI touch-ups rather than letting an algorithm freeload its way into rewriting anatomy.

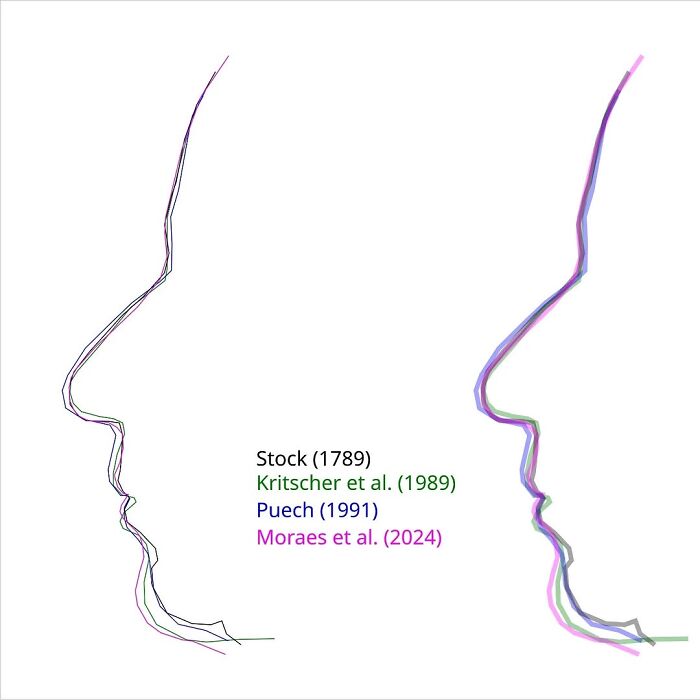

Multiple profile outlines stack together, showing where sources agree and where artists may have flattered

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

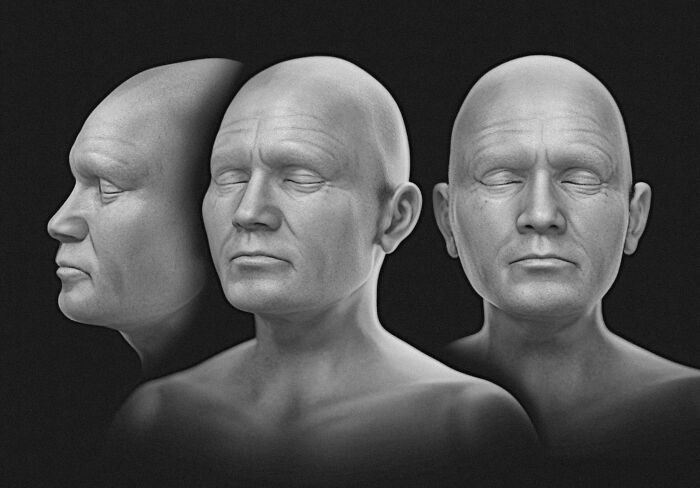

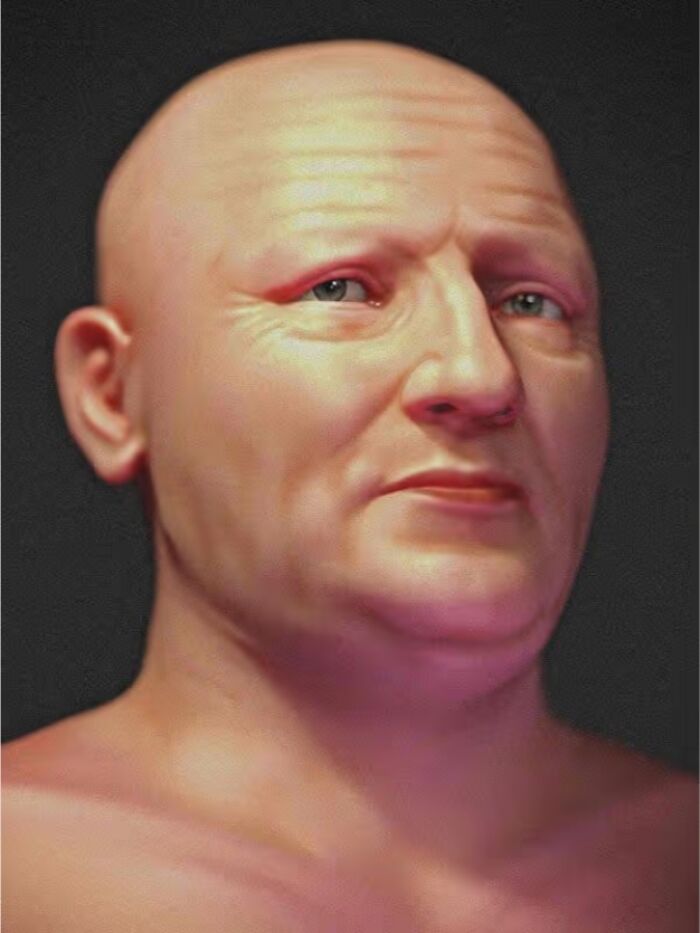

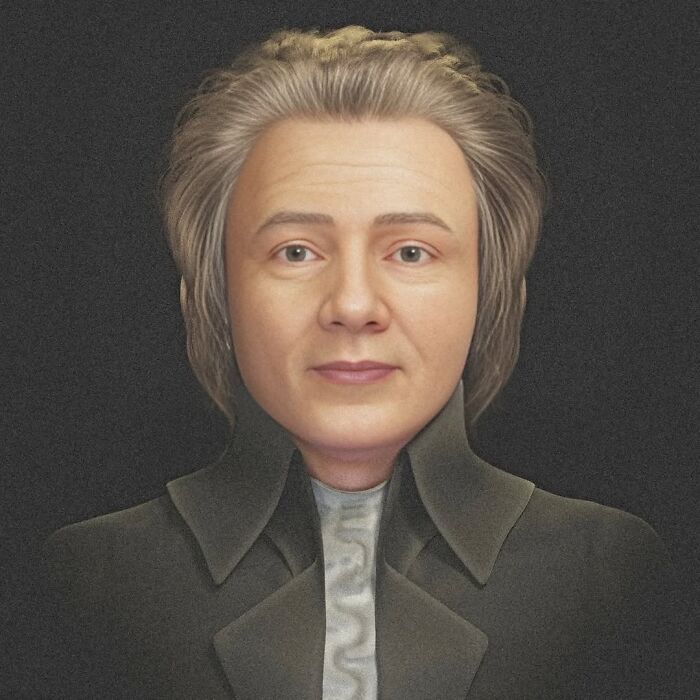

The “raw” 3D head emerges, then gets refined by adding hair, skin texture, and lighting

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

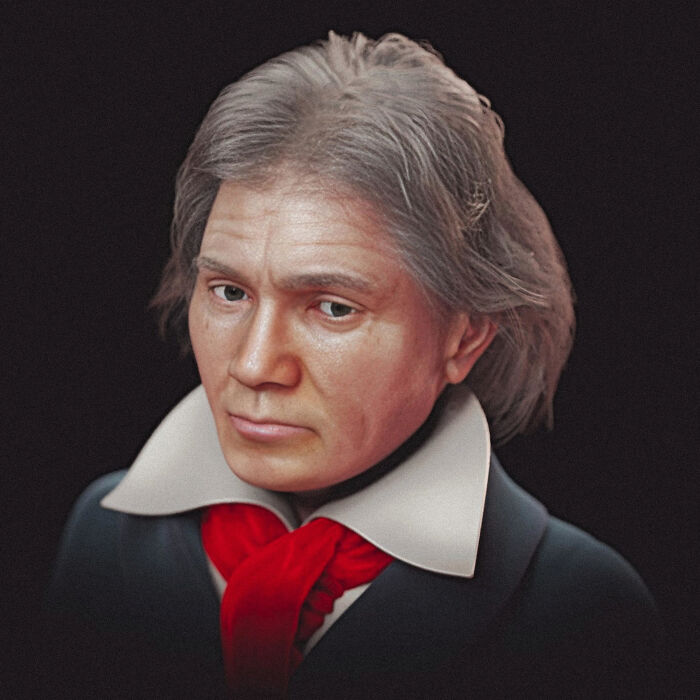

A more human, less mythic Beethoven emerges

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

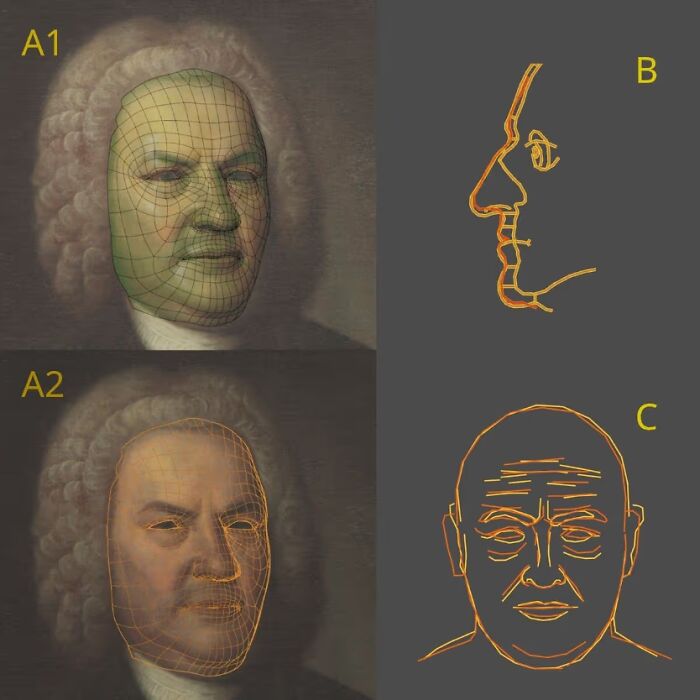

Bach begins with a different challenge: matching a 3D facial mesh to a historical portrait

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

The portrait becomes a measurement tool as Moraes maps facial planes and landmarks

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

A calibrated skull model, aligned profile, and head volume work together to shape the final model

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

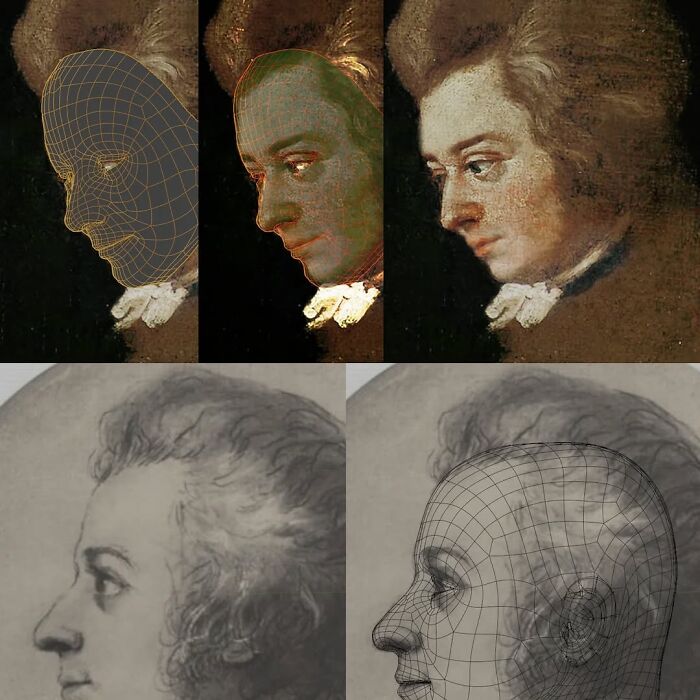

Mozart’s process starts with reference imagery, turning a painted profile into a usable 3D guide

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

A second reference angle gets matched in 3D, helping confirm the proportions of the brow, midface, and chin

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

A second reference angle gets matched in 3D, and compared to previous attempts at reconstruction

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

Mesh-on-portrait overlay: the face grid is adjusted until key points sit where anatomy says they should

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

The skull model and the facial “envelope” get combined, showing how the reconstruction is constrained by bone

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

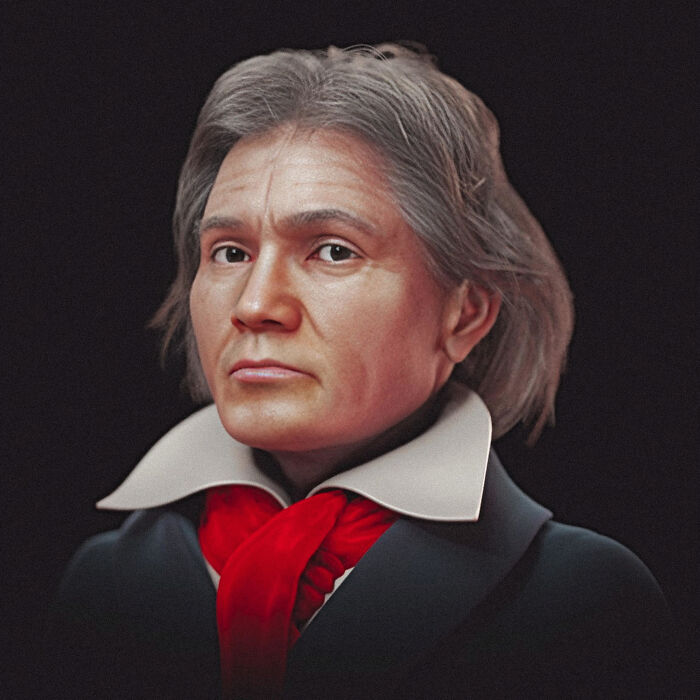

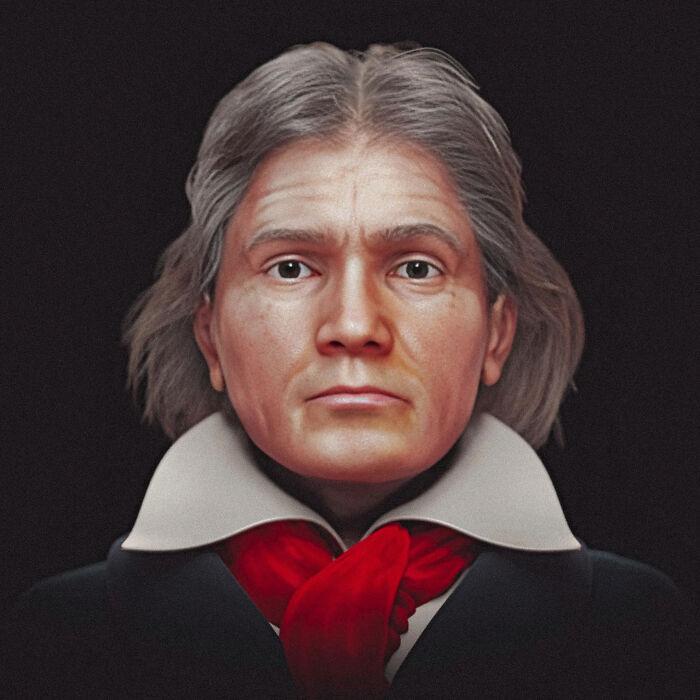

A clean 3D sculpt becomes a lifelike head as pores, shading, and subtle asymmetries are added

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

Mozart’s reconstructed face looks softer and more aged than in historical portraits

Image credits: Cícero Moraes

Explore more of these tags

Very interesting. When I think of Mozart I will always think of Tom Hulce in Amadeus. This rendition has the same sparkle that Hulce showed in the movie.

Very interesting. When I think of Mozart I will always think of Tom Hulce in Amadeus. This rendition has the same sparkle that Hulce showed in the movie.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

24

3