My Photographic Chronicle On Bipolar Disorder To Help You Understand It Better (25 Pics)

Almost four years ago, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Finding this diagnosis for me was a huge change (a positive one), which led me to start a journey that continues to this day, where the mental stability that I have is maintained. I lived through many things, and something curious is how the disorder began to show before I gave it a name. It showed through my photos.

The images that I will start uploading are selected photos from various projects, which I feel—interpreting them now—showed the symptoms of what we call bipolar disorder long before I could name them. I will upload them in a non-chronological order, sometimes accompanied by various things that I wrote over the years and telling the story, explaining how I experienced the manifestation of these symptoms and other thoughts.

“It is ‘on the spur of the moment’ that one should speak of psychological suffering. It is about one’s own field of action, at its very moment, that it should be grasped. After it has calmed down, dissipated, the spirit is too inclined to forget, or at least to minimize what he has been […] If one waits for the cure, the impressions that will remain will be vague, imprecise, without vigor and color” – Raymond Guérin, Le Pus de la plaie ( 1982, p. 32)

So, what is bipolar disorder? It is a mood disorder, which causes the person suffering from it to go from depressive episodes to hypomanic/manic episodes. It has treatment (pharmacological and psychological).

But we all have mood swings, some people say. And yes, all people have mood swings. But what differentiates the “normal” mood changes from those with bipolar disorder is that the latter turn out to be more extreme, last longer over time, and produce serious consequences, in addition to considerably reducing the person’s quality of life.

More info: Instagram | Facebook | notasdenochesdeinsomnio.wordpress.com

Photograph from 2012. Many years before diagnosis

When I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, after years of unexplained suffering and a bad experience with a psychiatrist, I came across a very overwhelming feeling: not being sure what my identity was. Not knowing who I was.

There were certain things I was beginning to learn that were symptoms of the disorder. The bad things, I was glad to know, were not due to a lack of character or will. But the problem was the “good” things. Some symptoms could be interpreted as coveted characteristics in the society in which we live, such as excess energy, exacerbating creativity, not needing sleep, and still being a highly productive and sociable person. Hypomania feels good. Nobody can deny that, but that well-being is always accompanied after periods of high irritability and then inevitably falls into depression. There is no way to stay on top without falling.

I remember being horrified at the idea—at the prospect of being medicated—that my creativity and energy “would go away.” That part of me would be “doped.” It was something that had me quite distressed. But I found a book called “The Bipolar Workbook” by Monica Ramirez Basco. This book had an activity that was a before and after. It proposed to think of different categories and filter them between being in depression, being “ok,” and being hypomanic/manic. It was this activity that made me see the difference between my personality and the disorder itself. So I never say “I am bipolar” but “I have bipolar disorder.” And on the part that most martyred me, that of creativity, I found that this is part of me, only that it depends on how it will express itself differently. If I am going through a depression and manage to write (I tend to write at those times rather than using other expression methods), the ideas that come out are the crudest and even poetic because I write from pain. On the other hand, if I am hypomanic, the pictures come out in thousands, at the speed of light. They are looser ideas, not so refined. But when I am stable, the creativity is still there, with the difference that I can take the ideas from the other two states and polish them, or create new ideas that I manage to focus on and work on better.

Achieving that differentiation was one of the keys to a treatment that today I see its fruits.

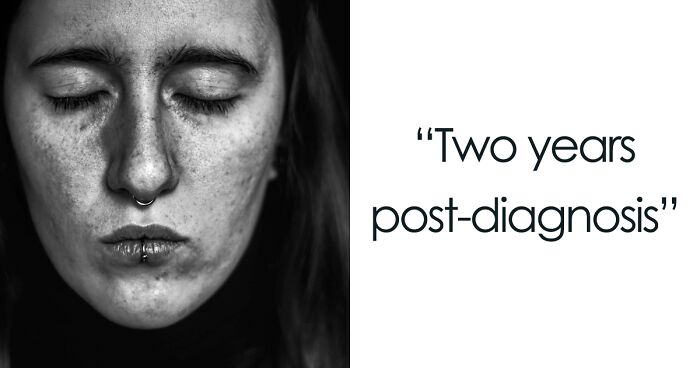

Photograph from 2019. Two years post-diagnosis

There are times when I like to compare depression to a foggy lens, but it could also be seen as a lens that lets you see yourself at such a level of detail that it’s almost impossible to escape noticing all your “blemishes.” I put it in quotation marks on purpose because the defects are something very relative and very personal. We all have flaws even if we don’t want to, and as our life passes, we perceive them more or less. Some people see defects in the physical, others in their behaviors or ways of being, others in absolutely everything. I would say that it is human to see flaws at some point. But just as we see defects, it is logical that we also perceive our virtues, to a greater or lesser extent, throughout our lives.

But what happens then during a depression? At that time, it is literally impossible to perceive even the slightest virtue. You analyze yourself at an incredible level of detail, marking every ugly thing you find no matter how small it is and—right here is the big problem—enlarging it in your head to an exuberant level, and that completely escapes reality. And the worst thing is not being able to control it (because we agree that we would not be talking about a mental health problem). Depression is not just sadness. It is not something that “is going to go away if you think positive.” Depression is something that dynamites you, boycotts you, makes you blind to whatever little good you have. Depression marks each of your pores, each stain on your being and invades you, consumes you, makes you agonize even though no one from outside can see it.

Photograph from 2016. One year before diagnosis

Text of July 10, 2018, post-diagnosis.

“A question that comes up a lot is how to help someone who has a mental disorder. The answer itself is quite simple: ask the person who lives it “how do you think I can help you?.” And not just ask, but listen without judging and doing what they ask.

It is also important not to advise in the air, especially if you are aware that you do not have enough information about the disorder in question. It is tiring to listen to people saying things that (despite having all the good intentions in the world) minimize what happens to you out of ignorance.

The objective is that the person who lives with it and their environment can communicate with confidence so that they can live their life in the best possible way.”

Photographs from 2018. Some months after diagnosis

I once asked myself: If I had to choose the worst symptoms of the disorder, what would they be? Three came to mind, and one was fatigue. That is one of the signs that are expressed physically.

There were many years of living with fatigue. Doing absolutely everyday things took energy from me that I didn’t see in other people. It seemed admirable to me that there were people who, after working all day, could come to their house and make dinner. I could not and did not understand why. It meant that every little thing was uphill.

I remember doing things that I loved, but inside I felt that at any moment, I was going to fall from exhaustion. I remember teaching a class where my eyes closed from time to time, not out of boredom; I loved classes, but because my body could not generate the necessary energy.

And this happened day after day, especially when I was in the depressive phase. It is not the same as having a day full of things and returning tired. It is not the same as ordinary tiredness. Therein lies the difference. You could have rested all the recommended and necessary hours and still not be able to get through the day. To this was added (not having the treatment) how much I was martyred for not being able to. Feeling like “I didn’t really want it enough” when it was something that just wasn’t under my control.

But after the diagnosis and being able to access more effective tools, both pharmacological and psychological, I eventually managed to get out of it. I highly value things that, for other people, are common.

Now I can get up early and circulate all day. Get home and make dinner for me.

Photographs from 2016. Some months before diagnosis

When someone is diagnosed with a disorder (such as bipolar or some other), that does not mean, especially if they are undergoing treatment, that the disease itself will influence any behavior that person has. As with anyone, someone can have a bad day and react accordingly without it being or becoming an episode and the same in the face of some very happy circumstance. If you believe the opposite, you will fall into encompassing the whole person as if it were just a diagnosis. That approach is totally incorrect because the only thing it achieves is to annul the person.

When someone is given a diagnosis, it happens that for their environment, it becomes the main—or even unique—feature to identify them. And with that, there is a problem. A disorder, disease, or condition is only one part of the person (understanding the difference between “being” something and “having” something is crucial). What happens is that the posture of “he/she is bipolar” is convenient for others because it exempts them from the effort to understand all the complexities that the person has and learn about the diagnosis and what it implies. It is much easier to think “such is this” instead of delving into why the person is feeling bad or how the family/friend’s actions may be negatively affecting that person.

I continue to maintain the same as always: you should not fight with the diagnosis itself. This is one of the first and most important tools that a person with chronic discomfort can count on to improve. What must be asked and attacked is that ease in which some fall before the diagnosis of someone close, the environment of the diagnosed person is crucial in their improvement, and this will only be achieved if the first step is that all parties access the corresponding information and understand that a person is a complete and complex world and not only one word.

Photographs from 2016. Some months before diagnosis

Euthymia refers to the standard and calm state of mind. Balanced. The period in which there are no episodes of mania/hypomania or depression.

I have been in this state for several months, and I cannot explain how happy I am about it. There are people with bipolar disorder who sometimes prefer mania because it feels good, but I would not replace stability with anything, personally.

In general, you are not always aware that you are stable, but I realize it and really enjoy it every once in a while.

How does it feel?

I remember the first time I felt it after years. I was in the library. That morning, I had taken medicine in the morning shortly after the diagnosis because I forgot to take it at night as directed. I was going to read something, knowing that I would not be able to concentrate, as always happened. But that time, it didn’t happen. I was able to read, understand what I was reading without having to review it more than three times, and when I realized it, three hours had already passed in which my head had not gone elsewhere.

Other times I realized this was in college classes. In an instant, I remember that I was giving all my attention to the level without my head leaving.

Or on the bus, I noticed that I was really present at that moment listening to music.

Stability for me means feeling calm, focusing when necessary, and analyzing the things that happen to me from a realistic perspective with its bad and good things. Being able to be productive and balanced idle. Basically, my head doesn’t go 200 km/h with unrealistic positive or depressing thoughts.

And I am honest with you. I am scared. I am afraid that someday this stability will disappear. I appreciate it too much. And relapses are part of bipolar disorder. But what makes that fear not so strong is that after four years and a lot of work, I feel like I have more ways to face an episode and be victorious. I hope when the moment comes that I’ll be ready.

Photographs from 2016. More than a year before diagnosis

What did I lose because of bipolar disorder?

I had never asked myself that question until I read it in a support group.

And thinking about it, I found for now four main things: Friendships, jobs, projects, and money.

The first goes back to when the disorder started to wake up, and I did not know it. It began with my apathy to meet with people I loved, which led me to isolate myself and that eventually (with all the reason in the world), these people stopped inviting me. This happened to me more than once.

About the jobs, the isolation and the little energy that I often had to interact with people led me not to be able to promote my services as I should, or to not take advantage of job offers because of that giant anxiety of having to interact. To this was added that seeing how other colleagues were doing very well would increase my feeling of frustration and uselessness, creating a vicious circle.

Regarding the projects, it occurred to me that being in hypomania, I organized and moved all the threads to carry them out. But the day came, and the same cycle was repeated. I didn’t have the energy, I lost my motivation, and I couldn’t perceive why I liked the idea.

Finally, money. This occurred primarily during hypomania. In that state, so many ideas seemed to me brilliant in which I ended up throwing money, such as buying things that I really didn’t need, doing activities or courses of things that did not interest me at another time (although the latter is not necessarily bad), or investing in something without really thinking about it.

This is when some say, “But I also spent money on things I shouldn’t have!” And all this that I mention can indeed happen to all people at some point, but remember that it is part of a disorder when these things occur together with another set of symptoms; it lasts a long time and deteriorates your quality of life.

That is why these things should not be taken lightly.

This specific photo is very important to me. Photo from 2016. More than a year before diagnosis

On September 1, 2016, within the framework of the project where I was taking a photo per day for a year, I did this one, and in the morning, I wrote a text that cost me a lot to publish. I was afraid of being judged, treated as useless for expressing that I could not handle everyday things in my life. I hardly published it because in the afternoon, I was feeling good again. But I did it. Basically, it expressed there what I now know was depression. I remember that I received many messages of support. However, I also remember that those messages did not feel quite right to me because precisely, they appealed to “cheer you up,” “you can do it!” when I was dealing with something that you don’t come out of only with the force of will, since what was happening still did not have its respective name. I’m going to leave here the last part of that text, which is the one that seems most significant to me:

“You feel silly. Because you know, you really know that thinking as you are thinking is not good. But how to combat what you feel? How to fight that shadow that looms over you every day, that shadow that covers any small detail that could make you happy, that shadow that always manages to win? And you run out of tools to climb the well, to get rid of the shadow. Because the ones you tried did not finish working or broke trying. Sometimes someone tries to help you. But the rope thrown at you is not strong enough to support your weight. And then you hide it because you are exposed. You are exposed to being told lightly, ‘you have to think positive, don’t feel bad.’

But that is the step to take when you came out of the well.

While you’re inside, the only thing left for you to do is climb, and you want, with all your soul, you want to find that tool that leaves the shadow behind.”

It never ceases to call my attention as at that time, what I was looking for was a tool, a word that seems so important to me because it was in the diagnosis where I found that tool and many more.

Photo from 2016. More than a year before diagnosis

I remember the first time they told me they were going to medicate me. That time, I accepted it blindly, as I was in such a deep well that anything that promised improvement was going to be okay for me. And it worked, for a while. It should be noted that at that time, I had the wrong diagnosis. Therefore the treatment was also improper.

Eventually, the relapses returned (that’s the story for another photo), and that situation led me to another professional who actually nailed it with what was really happening to me. And what that was going to entail, in the beginning, was new medication.

I was reluctant to take it. I won’t deny it. Having the antecedent of the previous medication, I was filled with doubts. What if that medication doped me? What if I “stopped being me” by taking it? What if it didn’t work? How was stability going to feel?

Taking psychiatric medication that is going to affect your nervous system and brain cannot be taken lightly. But we don’t have to be afraid of it either.

It is the professionals’ task to inform as thoroughly as possible so that one can decide for themself the course of action. To be able to balance between the benefits and the cons. It is also necessary to always clarify that medication alone is not enough to be effective. Psychological therapy and a good environment are mandatory to begin to overcome this.

Photo from 2016. More than a year before diagnosis

When you go through what is called “ultra-rapid cycling” (episodes last for days) or “ultradian cycling” (there is more than one episode per day), something that can be felt is the loss of identity. I went through that because of a poorly prescribed medication whose side effect for someone with bipolar disorder was precisely to cause such abrupt changes (since the episodes usually last for months). And one of the things I noticed the most was that feeling of not knowing “who I was.”

It is not just any loss; it is one at a profound level, which leaves you with a feeling of emptiness that there is nothing like. It is constant uncertainty. It is to feel a stranger within your own mind.

Your mood and everything that goes with it changes at such a speed that you are no longer sure what motivates you, what is good for you, and what is bad. You stop knowing what you want because your mood does not match the things that happen to you. Something good makes you sad, something bad makes you indifferent, and so on, a thousand more combinations. It is like living by hanging from a rope and constantly putting on masks since no one who does not experience it in their own flesh really understands it. And you want to pretend because you already judge yourself enough for someone from outside to come and do it too.

Photo from 2016. A few months before diagnosis

Anhedonia. “Inability to experience pleasure, loss of interest or satisfaction in almost all activities. Lack of reactivity to usually pleasant stimuli.”

I think I will never forget that time when good things happened in my life, but I literally felt nothing. I did not feel the pride I deserved. I did not feel the joy I had to have because that was worth it. I couldn’t take pleasure in absolutely anything, not even things that I loved doing.

To this day, I think about it, and I imagine, “what would it have been like to feel that way when my book came out?” That’s why I appreciated so much having been able to feel happy when that happened.

Not being able to feel causes a lot of frustration because the worst thing is that you can be aware of it and, despite really wanting to “get over it,” continue without feeling anything. This is why the arguments about mental health that proclaim “what you lack is willpower” are so silly. Those who say that do not understand that the person is already trying, sometimes in inhuman ways, to get ahead, and alone, it’s not enough.

Photo from 2019. Two years after diagnosis

Mania. So far, I have mainly related to one of the poles of bipolar disorder, depression. But today, I wanted to bring the other side: mania.

It is no coincidence that bipolar disorder is difficult to identify. It is frequently confused with unipolar depression because socially, it is well seen (and even expected) to have overflowing energy, productivity, and creativity. The point is that mania is not just that which even sounds good. Mania is spending days without sleep. It’s skipping meals because of how busy you are and not even realizing it. It’s doing so many things at once that you can’t finish a single one. It is having delusions of grandeur, feeling that you are going to change the world, or achieving your goals with great ease. It is becoming irritable with anything that works against you. It is frantic, constantly moving because the energy exceeds your body’s ability to distribute it. It is having thoughts at a thousand an hour and having blackouts. It is seeing what is really bad as not so bad, and what is good as exaggeratedly good. It is spending money that you do not have or do not owe on unnecessary things. It is going off to do activities without any parachute. It’s extremely sociable, in a way that you wouldn’t usually be.

Mania is not funny; mania is not healthy, nor is it “a quirky person.” With all that it entails, mania is a serious health problem and that, in bipolar disorder, is ALWAYS accompanied by ending up falling into a well, deeper and deeper if no net is laid.

What is mania? It is a set of symptoms among which can be found: Euphoria, high mood, hyperactivity, having energy without feeling the need to sleep, delusions of greatness, verbiage, racing thoughts, and risky behaviors, among others. In the photographs, I will talk more in detail about these symptoms and others associated with the disorder.

What is depression? It is a set of symptoms among which can be found: Sad or low spirits, loss of interest and enjoyment, changes in appetite and weight, insomnia/hypersomnia, fatigue, apathy, feeling of guilt and worthlessness, and suicidal thoughts, among others.

Photo from 2016. A few months before diagnosis

Not having any tool to interpret what happens to you and why you find yourself naked in front of the problems. These come and hit you. They cover you up to sometimes not even leaving you to breathe. You are helpless, exposed, vulnerable. And the first tool comes with calling things by name.

Photo from 2019. Two years after diagnosis

When something is named, it begins to become familiar. It is no longer seen as an unknown entity that only causes fear and confusion. What happens to you, you start to understand, and you stop blaming yourself because you know that something is indeed wrong, but now you also know that there are ways to improve. And even though the same problems rushing towards you before you come back, they no longer feel like meteorites on your skin. They wrap you, but this time without attacking.

Photo from 2016. A few months before diagnosis

I just realized that something wasn’t right that specific week in which I began to think about what to “get ready” before I left.

The percentage of people with bipolar disorder who will consider or will have suicide attempts in their lives is high.

I’ve been with suicidal ideas for a while. What I was suffering had me exhausted. I didn’t see any meaning in anything, not even the good things that could happen to me. And here I want to emphasize the exhaustion that I mention. It is not exhaustion from having a long day at work; it is not exhaustion from having a week of studying without stopping for a test. It is an intense physical and mental exhaustion.

There is a misconception that the suicidal person wants to stop living, and this is not the case; the suicidal person only wants to stop suffering. Another myth is that suicide is selfish. Nor is it the case, whoever thinks about this is genuinely convinced that for their loved ones, not being around is going to be for the best, that you are going to take a load off them, what you want is for them to be better (How could that be selfishness, right?)

When these thoughts are there, it is virtually impossible to perceive them in another way; the conviction level is almost whole. But sometimes there are anchors, things that make us realize that something doesn’t add up, that we don’t really want to do that. In my case, it was my animals.

At the time, that specific week in 2016, I had already thought about what to do with my photos, a little about the letters or my things, a little about the “how.” But it was when I thought about where or with whom to leave my animals that there was a “click” in my head. I realized that I could not conceive the idea of them being with someone other than me. It hurt me more not knowing what would become of them than everything else that I had been suffering.

What followed that was going to the psychiatrist for the first time. And there began another chapter in this whole story.

Photo from 2016. Several months before diagnosis

(Text dated 12/4/2017, a few months after diagnosis)

Something that always characterized me is that I like to search for information on my own. When I was diagnosed, I did exactly that. I looked for books, articles, studies to read.

I told my psychiatrist if he had material to recommend me. I explained to him this is a topic that I am passionate about, one I think is exciting. One characteristic of this disorder is that it is common to lose sight of who you are. Who are you, and what part is the disease.

One of the tasks in a book asked me to fill in a table about how certain aspects were in each phase. And there was a specific one that comforted me a lot.

I realized that no matter what state I am in, the creativity in me is always present. In high spirits, ideas (whether they make sense or not) flow easily. Being “normal,” the opinions are still there, making it easier for me to carry them out. But when my mood turns to depression, which is the most difficult time to cope, it does not matter that I can not get out of bed. It doesn’t matter if I don’t eat or if I lost my enthusiasm for everything. Even in this deplorable state, I can put into words or images what is happening to me, and I believe that this tiny act is what makes everything, even for a moment, okay.

I emphasize the depressive side of this is challenging to get past. Your head is against you, and it does not get out of it with a simple “think positive, and it will go away!” (In fact, advice, never say that to someone with depression, it is VERY counterproductive). That is why for me, what I said above is very important. I think that’s my little contribution to the world, that later when I’m better, I can go working, polishing. It is as if the depressive state gives me the raw material that I then have to process.

A bit of this is how my head works, which I seem to be starting to know from scratch. But I’m glad because being able to name the demons is the first step, not to drive them away, but to learn to live with them.

Photo from 2016. A few months before diagnosis

Something that can happen during hypomania/mania is risky behaviors that can sometimes border on the absurd.

Once I was giving a talk about this, and when I mentioned risky behavior as a symptom, giving an example of compulsive shopping, some girls started laughing at each other, saying, “It’s me!” I don’t know if it showed in my face that what they said struck me as disrespectful. It is not the same to buy things that you do not sometimes need, to spend money that you do not have on something you are genuinely and sincerely convinced that you need it anyway. It is common for people with bipolar disorder to go into debt or invest in things that do not make sense during mania. If they were stable, they would not do it (therein lies one of the main differences with a “common” behavior). And in each person with the disorder, this can be seen in different ways. Some people will spend on clothes, decorations, and travel—others on hobbies that occurred to them overnight. I was from the group of the latter. During hypomania, I did a thousand activities that had nothing to do with my tastes, and from several, I bought things (unnecessarily) after a single class. It was a time of spending a lot of money that I could have saved, but at the time, I didn’t realize it. As soon as the idea was planted in my head, it made sense in the world; I visualized myself generating skills in all that I undertook in a short time. “At times she feels that she is superior to others and experiences feelings of greatness” (quote is taken from the psychodiagnostic report they made me in 2017). I was really convinced that I was exceptional, and that was why I would develop specific skills at an unrealistic speed. It’s not a joke. It is not eccentric behavior. It is a problem that can have grave consequences, and that is why it should not be taken lightly because this is how you can end up facing a storm of problems that, during the depression stage, will sink you even more.

Photo from 2016. Several months before diagnosis

“You lack willpower.”

There is something that all of us who go through life (temporarily or permanently) with a mental health problem have faced: that people minimize our experience and our feelings.

The phrase I mentioned above is a clear example of this. But let me tell you that the problem is not that. A person with depression does not lack willpower “because he wants to.” It is the depression that takes it away, not the other way around. When your body and your head do not give you the minimum energy to live, no matter how much you want it with all your soul, it will not appear as if by magic (here we remember that we are talking about depression, not sadness, these are two different things).

And unfortunately, something that happens and many times in the closest environment is that they tell you these things, that speech of “I can handle everything alone, you can also.” Which leads to tripling the guilt that one already feels in itself. Are there really people who think that whoever is wrong is because they want to? It is important here to get out of that thought that because something served us, it will serve everyone equally. This is something that I mention a lot with all this I do: what worked for me may not work for someone else, and that’s fine. Each one takes what is beneficial to them from the experience of others.

Getting back. I know that those comments have a genuine good intention behind them, but the purpose, in this case, is not enough. Which makes me wonder why it is so hard for people to listen without immediately making a value judgment with so little information? Why do we have this culture of always wanting to provide advice or our perspective so installed? Why can’t we wait to hear the phrase “now that I told you this, I want to know what you think” or ask if we can comment before we open our mouths?

When we talk about mental health, let’s exercise attentive listening, listening without judgment because the feeling that we are accompanied and listened to can be the first thing that genuinely helps us not fade away.

Photo from 2016. Several months before diagnosis

Text from 05/31/2020, which goes a bit hand in hand with the previous photo.

“There are times that I have thought about trying some of the “solutions” that people told me for bipolar disorder. But later I remember that those people who speak so LIGHTLY as if they were experts are NOT going to be there to help me if something goes wrong. When we speak about mental health, we are not talking about bullshit, so check what you are going to say when someone tells you that they experience something like this (even if you are a relative of someone, it is never the same to live it from the outside). I trust that many have genuinely good intentions, but good intentions are unfortunately not enough.”

Medication is one of the foundations of treatment for bipolar disorder. But also one of the most complex things. Although there are specific guidelines, the medicine does not work in the same way in all people, which means that the effects are beneficial. They can also be beneficial, but produce side effects, or with others, they do not work or do worse. What should not be lost sight of (and this must be discussed with the psychiatrist) is that the medication has to make you feel better, not worse. And if you notice after a while that there is no improvement, you have to consider changing it.

It is also not the only part of the treatment. A pill will not improve everything by itself; it should help stabilize, but therapy and a favorable environment are equally essential and necessary parts.

Personally, my experience with medication has been good, and the only one I had problems with was the first one they gave me, a poorly prescribed antidepressant (because the early diagnosis was in itself wrong). This antidepressant made me feel great at first. Still, at the same time, it produced so-called “rapid cycling” (when episodes of depression and hypomania occur in concise periods of time). This was because that particular antidepressant is contraindicated for bipolar disorder.

After accessing the correct treatment, having the diagnosis, I considered leaving it. My psychiatrist wanted me to drop it almost cold turkey, which I tried, but it gave me a panic attack (I’ve never had one in my life). At the same time, I already knew from past experiences that leaving it like this produced serious withdrawal symptoms, and I was unwilling to go through that.

It turned out that on Facebook, I found a large group of people who were in the same as me, trying to safely quit that same antidepressant and had generated a system to quit gradually. I started to implement it. It took me a year and a month to do that process, but I managed to get it out of my system without any side effects. The photo is of that medication, the last day I took it. Back to the dose when I started, before the last.

Photo from 2016. Two years after diagnosis

Medication is one of the foundations of treatment for bipolar disorder. But also one of the most complex things. Although there are specific guidelines, the medicine does not work in the same way in all people, which means that the effects are beneficial. They are also beneficial but producing side effects, or with others, they do not work or do worst. What should not be lost sight of (and this must be discussed with the psychiatrist) is that the medication has to make you feel better, not worse. And if you notice after a while that there is no improvement, you have to consider changing it.

It is also not the only part of the treatment. A pill will not improve everything by itself, it should help stabilize, but therapy and a favorable environment are equally essential and necessary parts.

Personally, my experience with medication has been good, and the only one I had problems with was the first one they gave me, a poorly prescribed antidepressant (because the early diagnosis was in itself wrong). This antidepressant made me feel great at first. Still, at the same time, it produced so-called “rapid cycling” (when episodes of depression and hypomania occur in concise periods of time). This was because that particular antidepressant is contraindicated for bipolar disorder.

After accessing the correct treatment, having the diagnosis, I considered leaving it. My psychiatrist wanted me to drop it almost cold turkey, which I tried, but it gave me a panic attack (I’ve never had one in my life). At the same time, I already knew from past experiences that leaving it like this produced serious withdrawal symptoms, and I was unwilling to go through that.

It turned out that on Facebook, I found a large group of people who were in the same as me, trying to safely quit that same antidepressant and had generated a system to quit gradually. I started to implement it. It took me a year and a month to do that process, but I managed to get it out of my system without any side effects. The photo is of that medication, the last day I took it. Back the dose when I started, before the last.

Photo from 2016. Several months before diagnosis

Relief. There is something that the books do not say, or that the closest environment or professionals ignore, that happens to many people when they receive a diagnosis (if they consider it accurate). After the initial shock of such news, feeling RELIEF.

I feel that what may seem like a mere detail is something significant.

On my way to get to the name of what was happening to me, I was exhausted. Exhausted. Shattered. It was an extreme physical and mental fatigue. And what I want you to understand is this: that the feeling of pulling a backpack full of stones off of yourself is a healer itself. It’s a breath of fresh air after months or years of awful air. It is like a short break before the next hill (or mountain, it depends on each person), the one where you have to start doing things to improve with the latest tools that you now have. It is a break that gives you another energy.

Knowing that what was happening to me was indeed something real, with a name and treatment, and that I was not the only one, relieved me of the weight of feeling that I wasn’t someone who “could not cope with life like the others,” and predisposed me better to do what I had to do, at my own pace, until today and for the rest of my life.

Photo from 2016. Several months before diagnosis

What things did I do to get better?

When I received the diagnosis, I learned how bipolar disorder works, what it was due to, and other data. With the help of medication to stabilize a little first, I started doing things that were going to help that stability to stay. The pills are not magic, and it is not that taking them is enough. So what things did I do? Some were only at the beginning, others I keep to this day:

Keep learning what the disorder is and how it works.

Monitor my mood, using apps for that, or on paper. This was to detect if there were specific things (triggers) that could produce an episode.

Having that information and distinguishing the triggers, I could begin to avoid those that were not necessary for my life, and those necessary, work on how to cope with them through therapy. Some examples: going to bars could trigger a depressive episode. As it was not necessary for my life, I did not go to bars again. Overloading myself with information could precipitate me into hypomania, so I started to take care of that. Managing my work’s marketing was another trigger, and I did work in therapy because I couldn’t avoid it. Also, getting away from certain people from my environment. Sometimes it is necessary.

I started the type of psychological therapy with the most evidence that was useful for what was happening to me.

1) I kept a regular sleep schedule. I was careful to always go to bed at the same time or not too late. I can be a little more flexible with this, but it was crucial at first.

2) I stopped consuming alcohol (although I was able to do it again in time) or marijuana (which I prefer not to do since it destabilizes me a lot).

3) I listened to my body and started taking the medication at the time of day that I noticed the most effective.

4) Talked to my close environment about what was happening and provided them with information (although I consider that the environment has to do it on its own first)

5) Remember when you read to me that everything I tell is what worked for ME. It may not be extrapolated to other people’s experiences.

First photo from 2012. Years before diagnosis. Second photo from 2020, years after diagnosis

One day, for one of my photographic challenges, I took accidentally the second photo of this post. I couldn’t help but remember those weeks without being able to get out of bed, the insomnia, or not being able to bathe. Of the tangled hair that later hurt to untangle.

And I’m honest, I’m afraid of ever falling there again since I’ve been stable for a long time.

It is an unavoidable fear, which sometimes appears with power and other times it seems that it is gone, but it is always there, small and hidden. Latent (I like that word as a name for some exhibition).

But that fear is also a part of the engine to continue with what I have been doing to take care of my mental health. A necessary evil could be said. That dark part with which we live and with which we have to learn to get along.

Please, if when reading this it is born to say “you do not have to be afraid,” do not tell me that. Everyone has one fear, and this is mine.

Photo from 2016. One year before diagnosis

I want you to follow me in this thought and try to feel what I am going to describe: Imagine that you fell from somewhere high, but you managed to hold on to something. Now imagine the desperation of knowing that even though you are holding on … you begin to slip. It may happen that in the end you manage to hold on and someone helps you, or you may end up falling. Until a little time passes you will not know.

This, that despair is what it feels like when someone with bipolar disorder reached stability or some improvement, but something happens that makes them turn again to the side of depression. Sometimes it is because of something specific that happens, other times it seems to have no reason to be.

Those of us who have this disorder feel emotions. There are times when medication can appease them, but if something good happens to us we are going to rejoice, and if something bad happens to us we are going to be sad or angry, like anyone else. And that does not mean that a joy or a sadness will end in an episode.

But there is a difference. We know very well what it is like to feel bad for a LONG time and that that time seems eternal. We know how it is that the external event that produced the discomfort (if there was one) has happened and still we cannot get out of that well. And we do not want to go back there, we do not want to feel surrounded by that darkness with no apparent exit … Then when it happens that we feel bad, no matter how justified it is to feel that way, the fear of falling, the despair of not being able to hold on to it is very large.

As I have said before, I do not want to be told not to be afraid, because we all have some fear, and perhaps with these words you can understand it better.

Photo from 2016. More than a year before diagnosis

Symptom is a project that begun, unintentionally, from a refusal. I wanted to talk about bipolar disorder in a specific institution where they closed the doors for me … And giving another twist to what I do – not only keeping my testimony but also attaching my artistic work – this came up, that first, it was going to be a face-to-face exhibition (which I hope will be in the not-so-distant future). I’m glad that things turned out the way they did because it allowed me to re-interpret my work from another perspective, with ease, and with new tools.

I was able to understand things that I experienced several years ago and put them into words. I was able to develop better all this of which I speak, and beautiful experiences arose from there.

I close this project, but not completely. I will surely continue to publish photos that I have left outside, I will continue writing about it, I will continue talking about bipolar disorder because after all, even though I am now asymptomatic, it is something I live with.

It is no coincidence that I chose this photo to close it. It was one of the first that I did really wanting to show what I was experiencing at that moment, in that case, the racing thoughts, the saturation linked to the overstimulation. In most of the previous photos, I was not fully aware that there was a problem, but in this one I was.

I hope this project has been useful to you in some way, either to learn about what bipolar disorder is, to understand it better, or to feel in company if we share a diagnosis. And I also hope to see you if I am given the chance to present it somewhere in person.

I feel like this was just the beginning of something maybe bigger.

A necessary clarification: I am simply a person with this diagnosis who freely talks about it. I am not a mental health professional, so I am not qualified to advise on particular cases. My mission is to provide information and tell my experience, hoping that other people can find it helpful to understand a little more, feel accompanied, and help remove the stigma and myths found on this.

If you have questions or suspect that you may be experiencing something like this, do not hesitate to consult a mental health professional. Do not stay with what you have read on the internet. There is nothing wrong with going to a psychologist or a psychiatrist. Just as we take care of our physical health, we also have to take care of our mental health.

6Kviews

Share on FacebookExplore more of these tags

I love this. I have bipolar myself and the perspective you've put on it is amazing. Thank you

Most of them are really, really, really good! I studied art and photography, so i looked at a lot of stuff. Your pictures really moved me. You are very talented, please keep up and enjoy being able to express yourself so wonderful!

You are amazing at this the photos are amazing and the way you can show a picture-perfect story behind them is amazing. You have a lot of talent.

Magali Agnello, you have given us a wonderful insight to Bipolar Disorder. I have been on the rollercoaster and seesaw of depression caused by childhood trauma (sexually abused by a family member). The one person who finally clicked that it was not only depression I was suffering, but bipolar disorder was my family GP. The day that went for a checkup, he asked me a few questions, checked a big book on his desk and you could see his eyes light up. He explained to me how and why he reached this diagnosis. This doctor had seen me for over 25 years as a patient. Was he wrong? No, I am on the right meds and I am coping for the first time in 3½ decades. I thank you from the deepest part of me, as a woman too, for sharing your story. Let us hope that this helps other people too.

Thank you ♥ I'm glad you found the diagnosis and correct treatment.

Load More Replies...Thank you for sharing your story. I know several people who suffer from Bipolar disorder, and being able to get a glimpse into some of what they deal with on a day to day basis certainly helps me to understand a bit better. Thank you again.

Beautiful photographs, thank you for sharing. And for sharing your journey.

Thank you so much for sharing your story. My mother has been diagnosed with this disorder for ten years, and we have known something wasn't alright with her behavior for ten years prior to that, but we could not get her to seek treatment. She is a very private person and refuses to talk to us about any of what is happening to her, but what you are saying makes so much sense for most of her behavior during all of my childhood. It took her 8 years to finaly find the good medication and dosage, which is the part that scares me the most when i think about getting a diagnosis for myself. Whenever i am in this "in between moods", i know that i should want to seek help and always find an excuse (i can't start medication now because of my studies/my new job... or for the last four years, because who will care for my two boys if i am as out of it as my mom was ?). But i am scared of not seeking change in my moods and behaviors. I am scared of hurting them as she hurt me, and sometimes, just sometimes, i wonder if they wouldn't be better off being raised away from the madness that are bipolar people. I have three paths of life as i see it : faking it and convince me that i am a healthy environment for this two boys ; let them be raised by the father and be the parent only there 96h per month, hoping that less exposure to my swinging behaviors will hurt them less, or seek treatment and miss all of their childhood. I have been rambling to you for some time now (sorry about that) so i'll just say thanks again for sharing, and good luck for the next part of your life.

I love this. I have bipolar myself and the perspective you've put on it is amazing. Thank you

Most of them are really, really, really good! I studied art and photography, so i looked at a lot of stuff. Your pictures really moved me. You are very talented, please keep up and enjoy being able to express yourself so wonderful!

You are amazing at this the photos are amazing and the way you can show a picture-perfect story behind them is amazing. You have a lot of talent.

Magali Agnello, you have given us a wonderful insight to Bipolar Disorder. I have been on the rollercoaster and seesaw of depression caused by childhood trauma (sexually abused by a family member). The one person who finally clicked that it was not only depression I was suffering, but bipolar disorder was my family GP. The day that went for a checkup, he asked me a few questions, checked a big book on his desk and you could see his eyes light up. He explained to me how and why he reached this diagnosis. This doctor had seen me for over 25 years as a patient. Was he wrong? No, I am on the right meds and I am coping for the first time in 3½ decades. I thank you from the deepest part of me, as a woman too, for sharing your story. Let us hope that this helps other people too.

Thank you ♥ I'm glad you found the diagnosis and correct treatment.

Load More Replies...Thank you for sharing your story. I know several people who suffer from Bipolar disorder, and being able to get a glimpse into some of what they deal with on a day to day basis certainly helps me to understand a bit better. Thank you again.

Beautiful photographs, thank you for sharing. And for sharing your journey.

Thank you so much for sharing your story. My mother has been diagnosed with this disorder for ten years, and we have known something wasn't alright with her behavior for ten years prior to that, but we could not get her to seek treatment. She is a very private person and refuses to talk to us about any of what is happening to her, but what you are saying makes so much sense for most of her behavior during all of my childhood. It took her 8 years to finaly find the good medication and dosage, which is the part that scares me the most when i think about getting a diagnosis for myself. Whenever i am in this "in between moods", i know that i should want to seek help and always find an excuse (i can't start medication now because of my studies/my new job... or for the last four years, because who will care for my two boys if i am as out of it as my mom was ?). But i am scared of not seeking change in my moods and behaviors. I am scared of hurting them as she hurt me, and sometimes, just sometimes, i wonder if they wouldn't be better off being raised away from the madness that are bipolar people. I have three paths of life as i see it : faking it and convince me that i am a healthy environment for this two boys ; let them be raised by the father and be the parent only there 96h per month, hoping that less exposure to my swinging behaviors will hurt them less, or seek treatment and miss all of their childhood. I have been rambling to you for some time now (sorry about that) so i'll just say thanks again for sharing, and good luck for the next part of your life.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

53

13