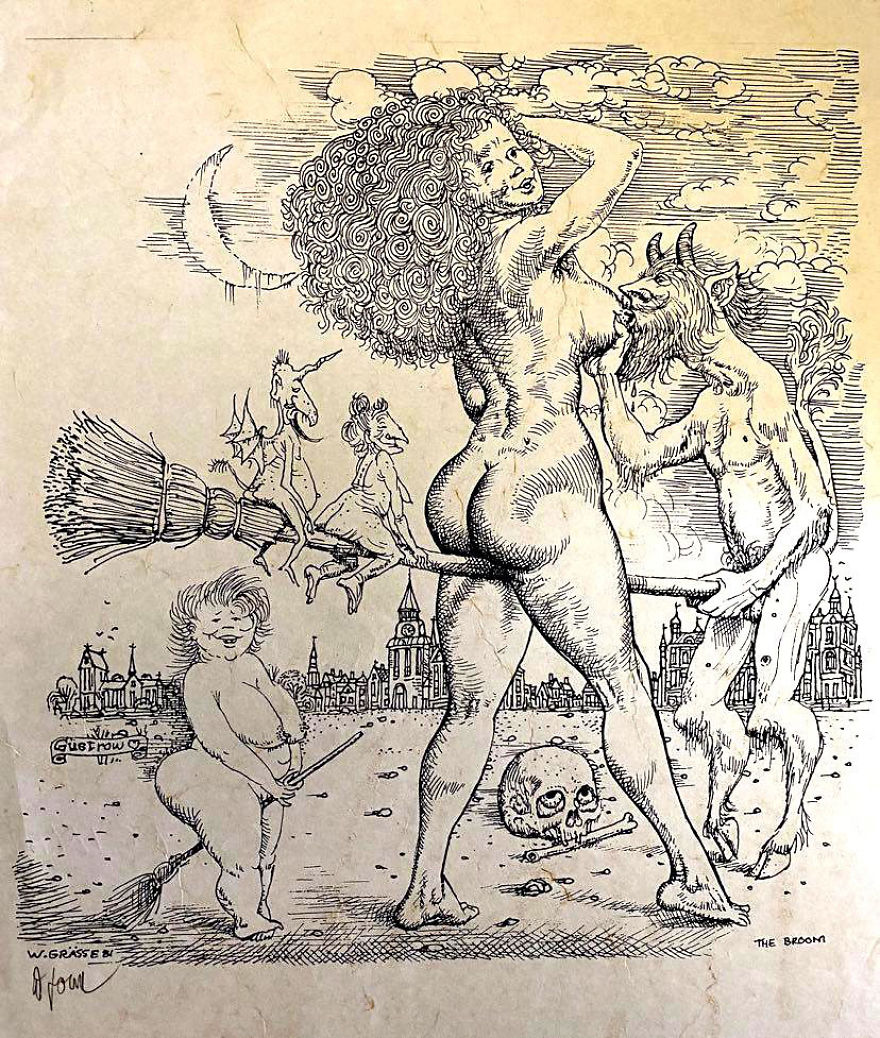

“We Must Accept The Ultimate Truths” The Paintings Of Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008)

“His time is out of joint and there are no contemporary labels for the style:

It is fine and meticulous with that half-demented blend of the decorative and the passionately descriptive that informs the painting of late gothic and reformation Northern Europe.

One thinks of Altdorfer and Cranach and Darer, and even of Raphael done over by Hieronymos Bosch.

In part the artist puts his grotesque talent to simple archaistic purposes, repeating early religious pictures that seem to match his temperament.

Sometimes he attempts, not quite successfully, to update them by crucifying Jesus on a warplane (propeller driven World War II: one takes a stab at the autobiographical implications).

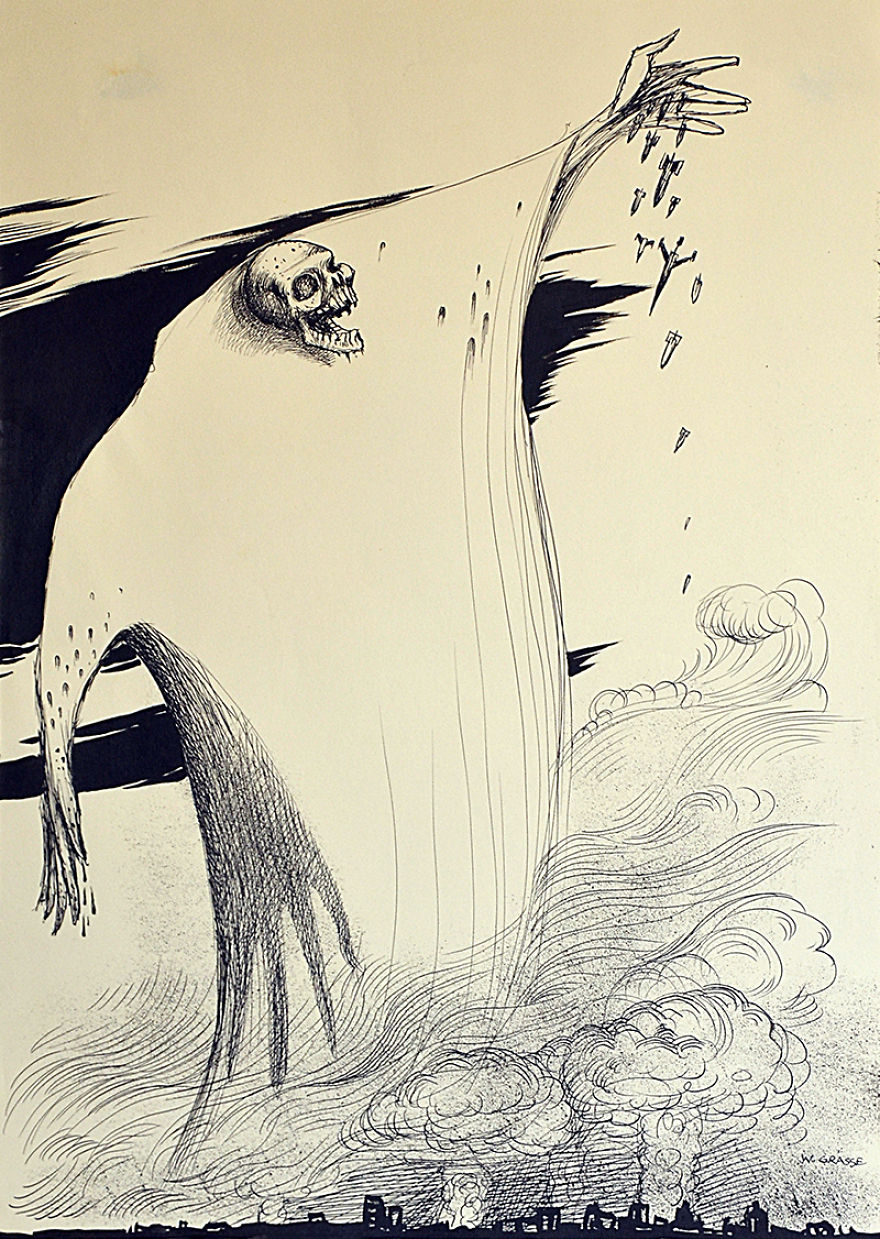

More successfully, he turns the manner of Dürer’s engravings and woodcuts into less clumsy allegories: the terrors and moral tales of the fifteenth century re-told for the twentieth, in terms of an apocalyptic horseman with a sub-machine gun.

Or again, he uses a brush no less skillful than Da to create an airless allegory with distortions that, although not properly speaking surrealist, nevertheless graft private idiosyncrasies on to public symbols, so that one has a slightly uncomfortable sense of looking in on aspects of the artist’s personality that are not ordinarily made so accessible.

Yet the two or three relatively detached, comic works, seem trivial in comparison.

Wolfgang Grasse is a temporal misfit, with artistic skills and attitudes that stand out, in our time, as a witch or an alchemist stands out.

He is a genuine and remarkable anachronism, only seeming to share the same convenient vehicle as the fashionable gothic novelist. “

Power – and a style that has no label

Professor Donald Brook of the Sidney Morning Herald, 1968.

by Stephen Romano, with quotes from an interview with Wolfgang Grasse and Damian Michaels from November 1999

Wolfgang Grasse was born in 1930 in Dresden, Germany.. He spent his formative years growing up with intellectual curiosity in a city that was considered a cultural jewel of Europe .

13–15 February 1945, at age 15, Grasse saw first hand what is in historical infamy “The Dresden Bombings”, a British-American aerial bombing attack on the city, when over a thousand British and American warplanes dropped more than 3500 tons of explosives on the city, causing a horrific fire storm which killed more than 22,000 people and destroyed the city. Grasse had said the day after the bombings he walked through the remnants of the city and witnessed the destruction and death and charred corpses. This was the first event which traumatized the artist.

Grasse left shortly after to study painting with his grand father Friedrich Grasse who was an acclaimed painter in Italy. This would be the only technical tutoring Grasse would ever receive in his life time.

“My grandfather painted realist paintings. He was particularly strict with me with his teachings, but also he believed in my own abilities. He warned me from a young age of the brainwashing effects and influence of the teachers of art students at the time. When the war ended I escaped Dresden alone to Italy in search of my mother. I walked some 500 miles through the chaos, destruction and misery that surrounded me on this journey. I was shot at near the Austrian border, however managed to arrive in Villa D’ogna close to Bergamo where my mother lived, though in a wretched and filthy lice-infested state, near death. She was very young and beautiful and I instantly felt love and awe for her. I painted a great deal and was attracted to the painters of Otto Runge, Caspar David Friedrich and all of the German Romantics. Italian art seemed quite strange to me at first but I did like Mantegna am Archimboldi and later Crivelli. I studied in the Scuola Germanica, Porta Venezia, in Milano. M) art was full of introversion and death. I was not aware of the Vienna School at that time. It was in its formative stage around that time. By them however, I had already invented my own mystical/gothic style and specialist technique. “

Two years, 1948, later he would return to a now divided Berlin.. To earn his living, Grasse built a cart which he would cross over into east Berlin with to sell sausages. One random day, his fate would change forever as the guards found his activity suspicious, and decided to search him. They found on him a hand drawn picture of Stalin on the gallows. One of the guards wanted to just let him go, but the other wanted him arrested, which after some back and forth, he was.

Grasse was tried as an “enemy of the state”,at first the sentence was death. His sentence was later reduced to 25 years at hard labor in a Gulag in Poland, where Soviet and foreign prisoners, including prisoners of war, dissidents, political prisoners, “enemies of the state” and common criminals who were contained and used as forced labor. Gulag prisoners could work up to 14 hours per day, toiling sometimes in the most extreme climates, prisoners might spend their days felling trees with handsaws and axes or digging at frozen ground with primitive pickaxes. The large majority of prisoners at most times faced horrific conditions, meagre food rations, inadequate clothing, overcrowding, poorly insulated housing, poor hygiene, and inadequate health care.[1]. Grasse has said the only way he survived this ordeal was by bribing the guards with his drawing of their family members or erotic subjects in exchange for extra food and protection.

“To the Soviets, any threat against Communist ideology was a greater crime than murder or threat against life. I was sentenced to 25 years imprisonment with hard labour. As prisoners we always had secret deals in place with the Russian guards. I often drew erotic pictures for them, which assured me the constant supply of pencils and paper scraps with which to draw even though it was a forbidden activity. In 1949 there was a changing of the military guard at the prison and the Germans took over. Everything instantly became tight and strict with enforcement. The food supplies worsened and I suffered from tuberculosis of which many prisoners died. A girlfriend at the time would send me food parcels and I honestly think this saved my life. At this time, I started to draw imaginative images and erotic pictures. Apart from drawing dreamworlds, I read a lot of Russian literature: Lermontov, Gogol, Dostoyevsky, Fadejev and Tolstoy. I appreciated also the great Russian realist painter Ilja Repin. When released after eight years I had no one to stay with and I was evicted from the DDR (Soviet Zone) and ended up in West Germany. A great poet and friend who was a fellow ex-prisoner was released earlier than I and was teaching at the time at Bonn University, and was able to provide me with a home for the time being. .. The prison conditions were overcrowded. We were contained in large hall rooms of up to 400 prisoners. It was easy therefore to conceal paper and pencil. I produced some 6000 drawings over those years, all of which were lost except 48 pieces smuggled out by a comrade and subsequently exhibited in the City Museum in Dresden 1996. “

The inmates from the prison were released in 1956. Grasse would return to Berlin and work for 10 years as an illustrator and began to seriously focus on his career as an artist. Very few works by the artist from this period have survived. Those that have remain in private collections mostly as promised gifts to cultural institutions.

Grasse decided to immigrate to Australia in 1968, first living in Sidney for a year, then re locating to the bucolic Penguin, a town on the north-west coast of Tasmania. Wolfgang Grasse would spend the rest of his life there, perpetuating his art, writing and illustrating several children’s books, often traveling to asian destinations such as Philippines and China where he completed a now lost film on Chinese culture, and working as an illustrator.

“I often dreamed of faraway lands wondrously and especially for some reason of Australia. It was somehow quite crazy but one day I simply decided to move to Australia. I had already sufficient knowledge of the conditions of this land and the appeal of the Australian way of life, free and easy going; I was not disappointed when I arrived here. I became an Australian citizen in 1973. “

Grasse has said while life in Tasmania was gratifying, he continued to suffer from vivid nightmares to the extent of which he remained in a unstable state mentally.. He would say that was never really sure what the reality was, if he was actually in Tasmania enjoying a life of peace, tranquility and creativity and only dreaming of his past trauma and ordeal, or if he was indeed still trapped in the Polish gulag, suffering horrendous conditions and starvation and only dreaming of tranquility.

” My art theme is life and death, the dark and light, the high and low of our existence. We must accept the ultimate truths. “

In 2008 his wife and muse died tragically in a swimming accident. Wolfgang Grasse dies of a broken heart a few days later.

“It is important to read extensively; translate and transform our present world into your fantastic art. Learn all the techniques at your disposal. Do it the hard way if you must, be versatile. Learn from the old masters, they have a lot to offer still. Study hard and don’t be ashamed to strive for perfection and to be ‘academic.’ Do not be one-sided; the universe is full of shapes and surprises. We live in a rich colorful world. Don’t diminish your abilities. Follow your heart and be universal. If you want to create a new powerful universal art, you do need talent but also imagination and technical skill. “

{1}https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulag

More info: monsterbrains.blogspot.com

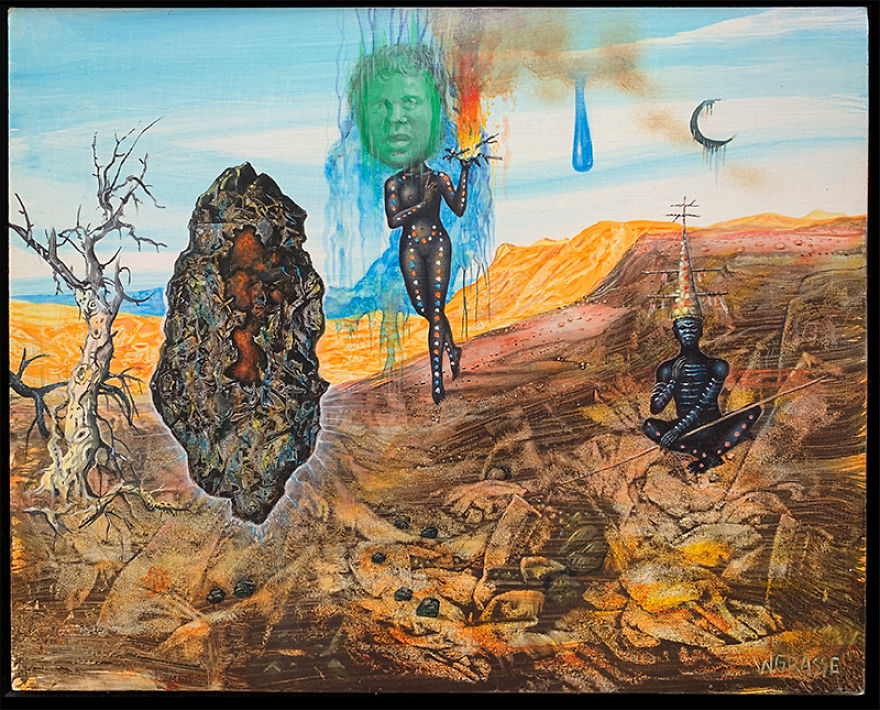

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Dresden” 1977

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Gustrow” 1977

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Firestone” 2004

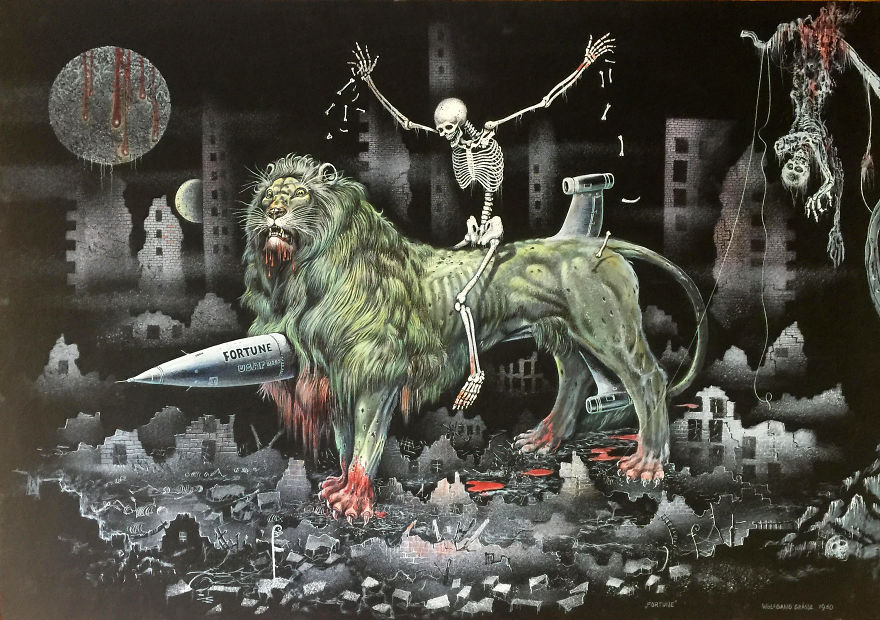

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Death’s Victory” 1960

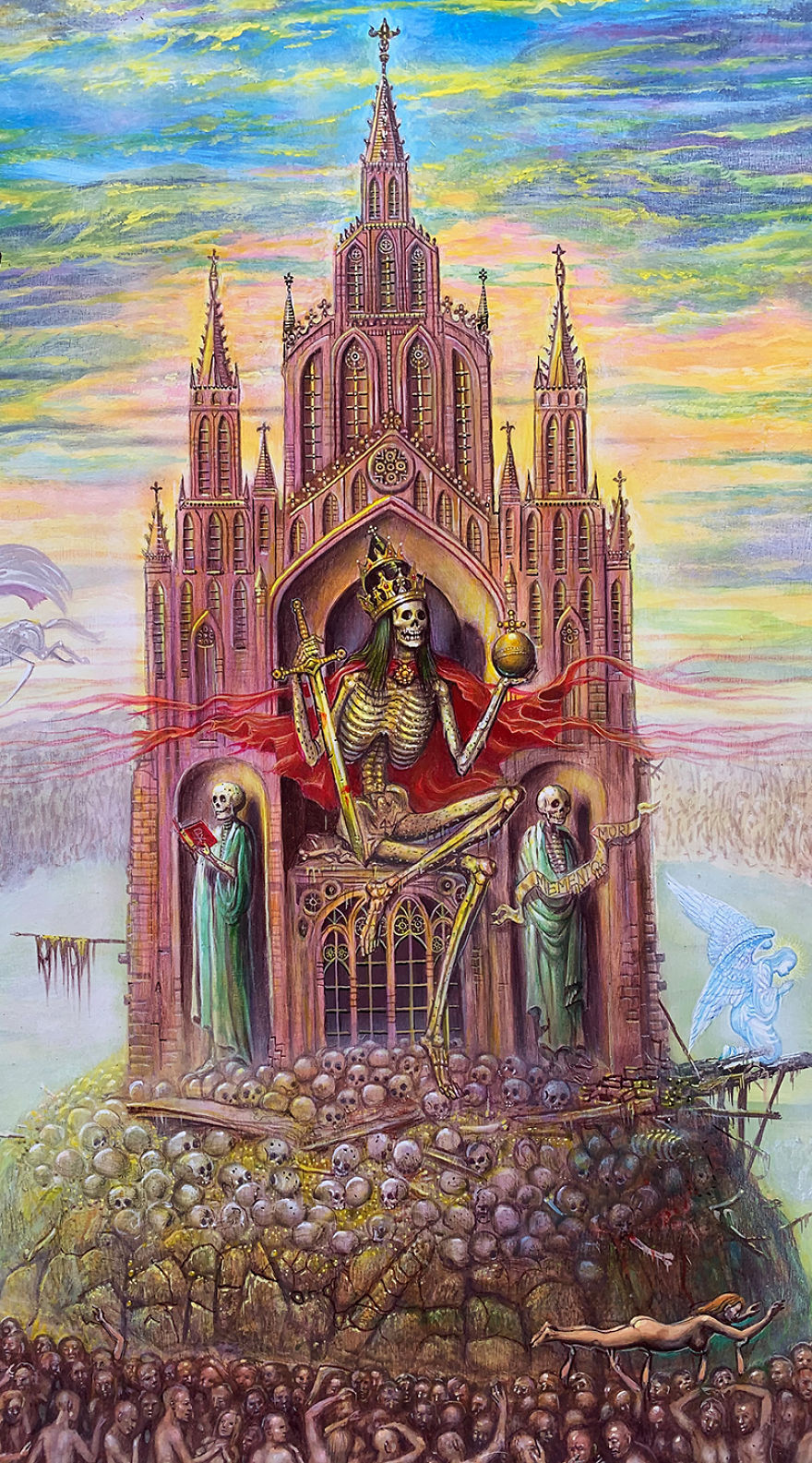

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Kingdom of Death” 2000

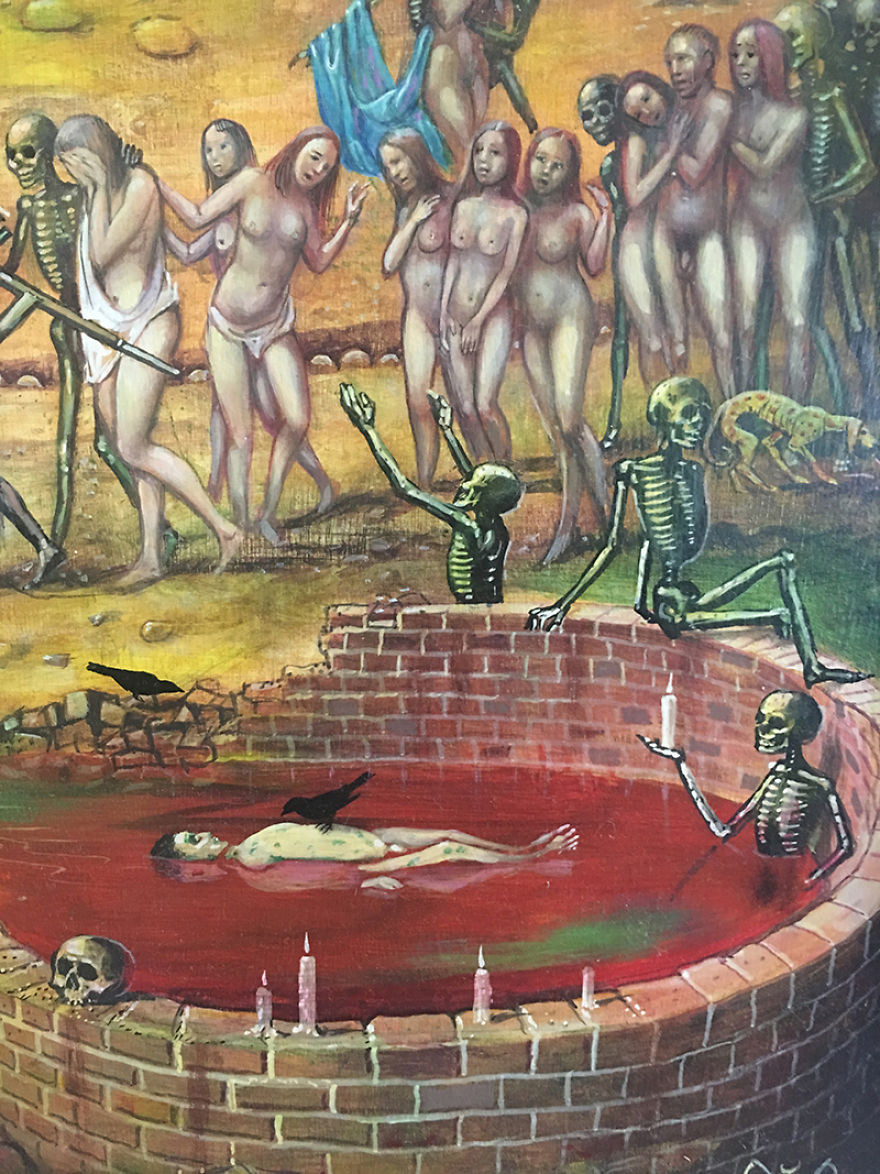

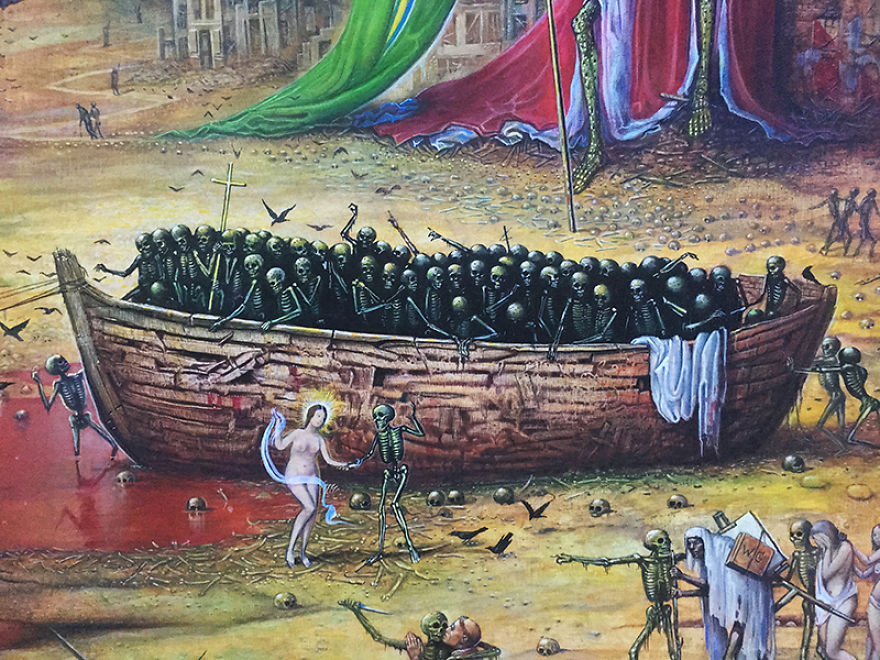

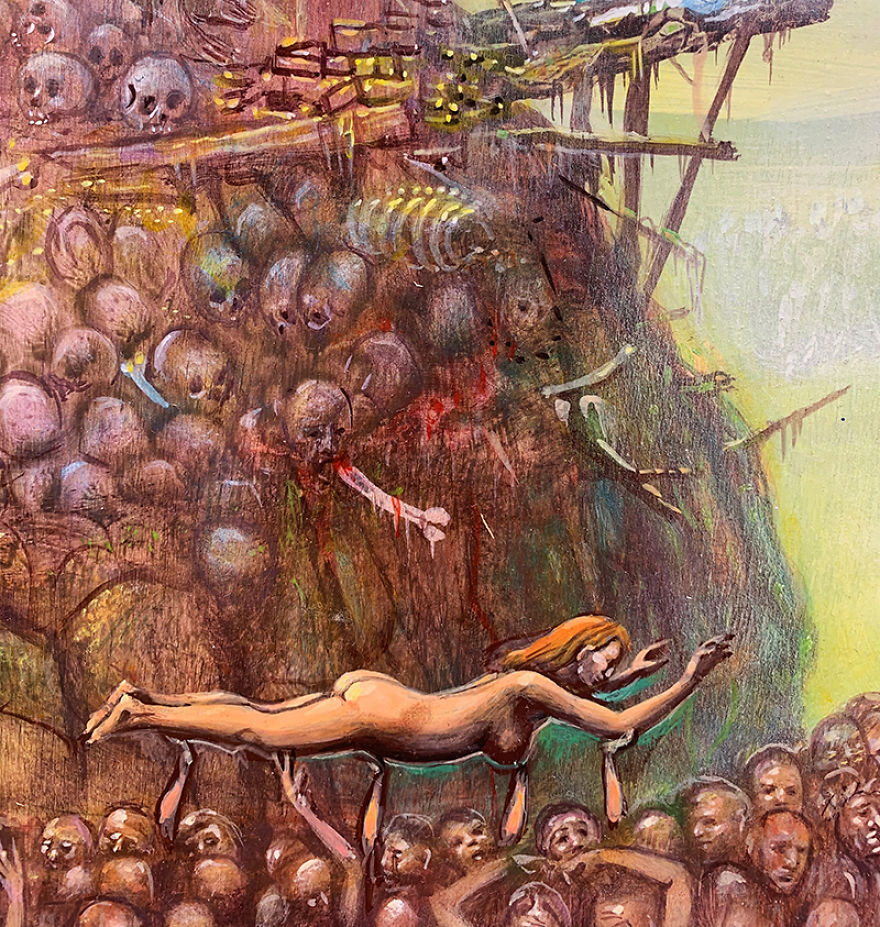

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Kingdom of Death” detail, 2000

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Kingdom of Death” detail, 2000

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Kingdom of Death” detail, 2000

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Kingdom of Death” detail, 2000

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Kingdom of Death” detail, 2000

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” 1983

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” detail, 1983

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” detail, 1983

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Throne of Death” (also titled “Merry- Go-Round”), 1999

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Throne of Death” detail, 1999

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Throne of Death” detail, 1999

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Throne of Death” detail, 1999

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Throne of Death” detail, 1999

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Throne of Death” detail, 1999

“Der Wahnsinn” (The Madness), ink on paper, 1958

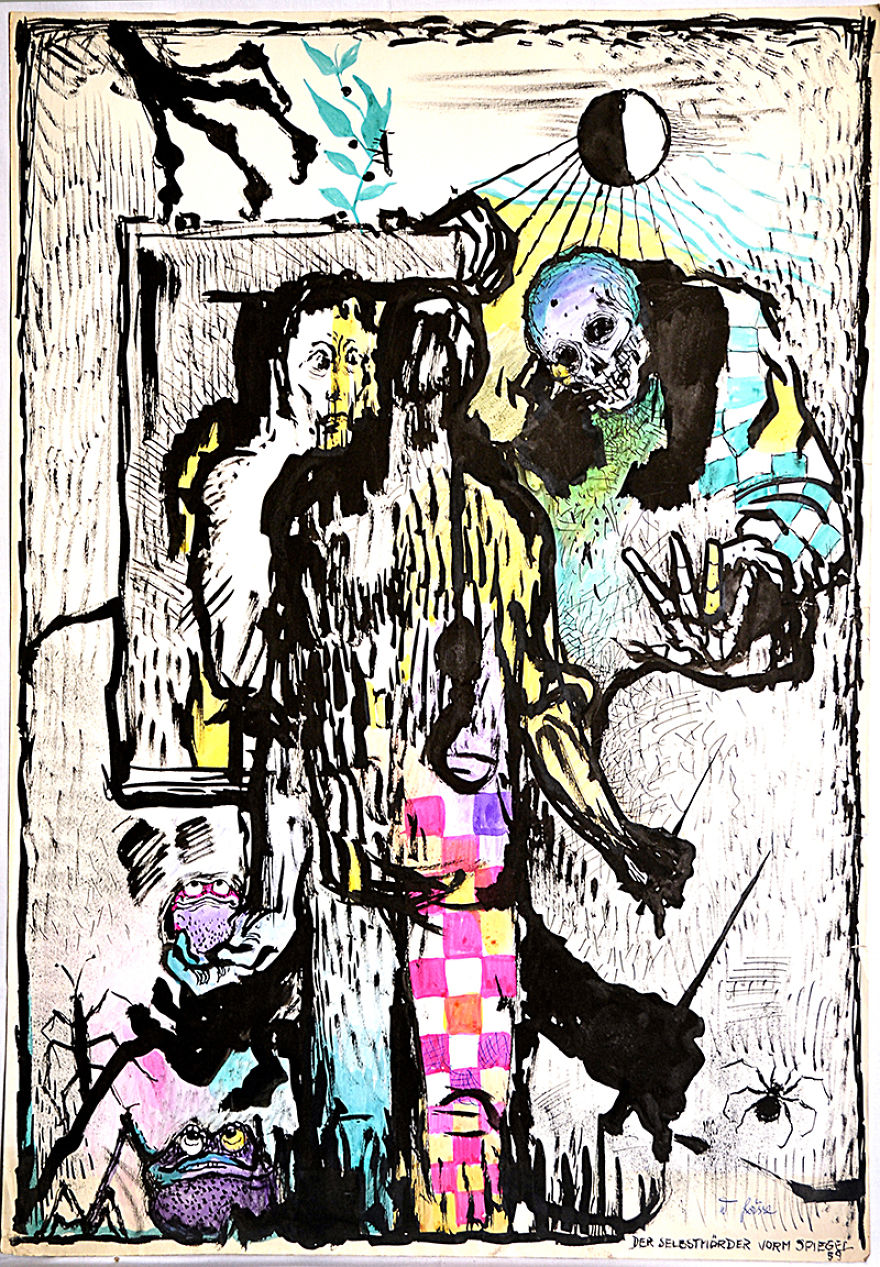

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Der Selbstmorder Vorm Spiegel” (The Suicide in Front of the Mirror), Ink and acrylic on paper, 1959

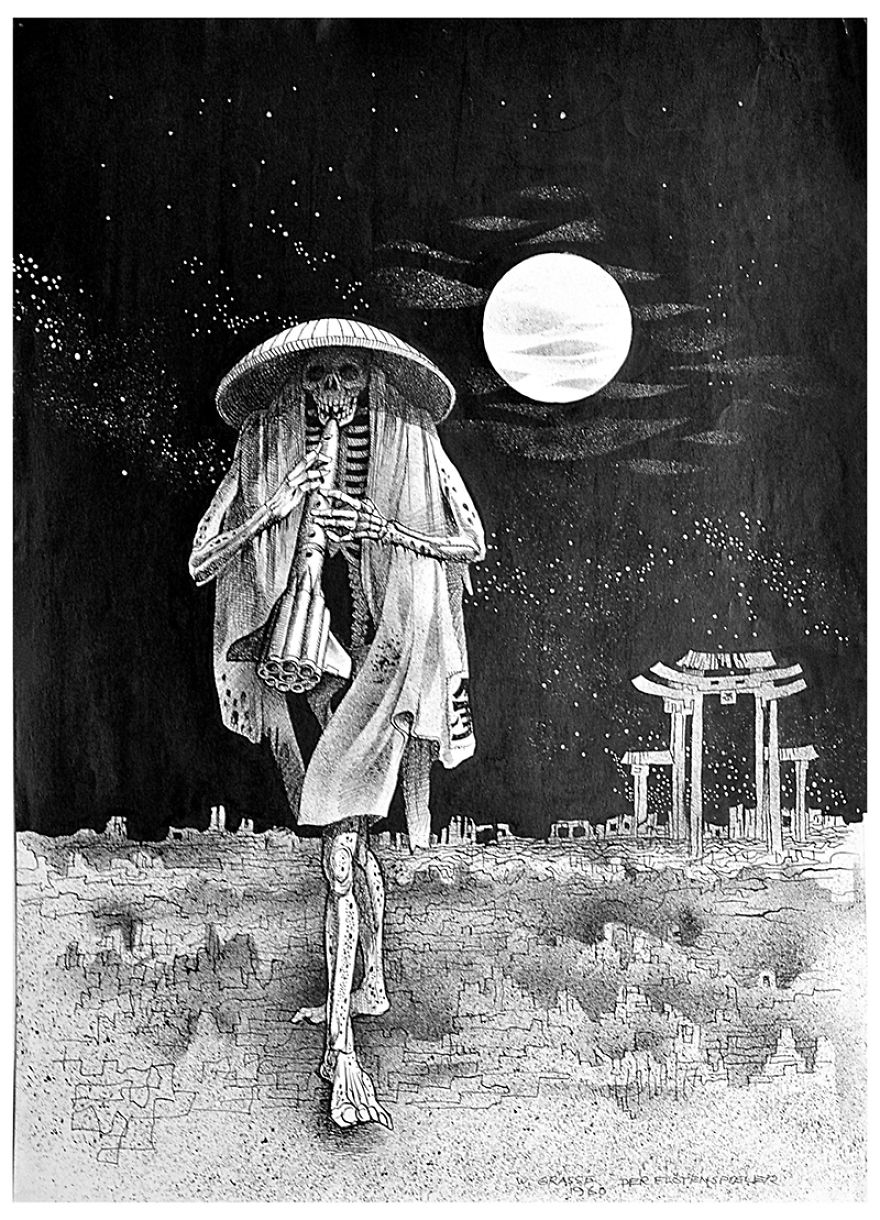

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Der Flotenspieler” (The Flute Player), Ink on paper, 1960

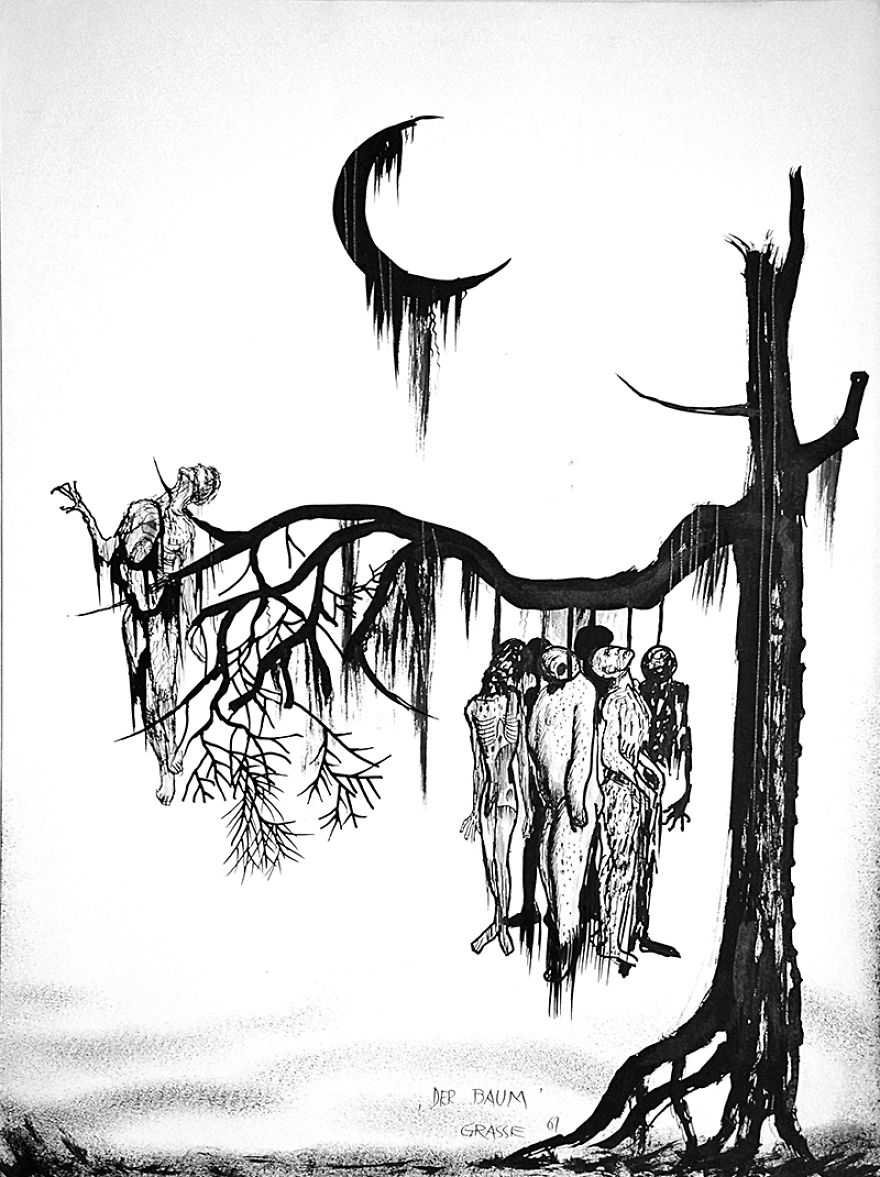

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Der Baum” (The Tree), Ink on Paper, 1961

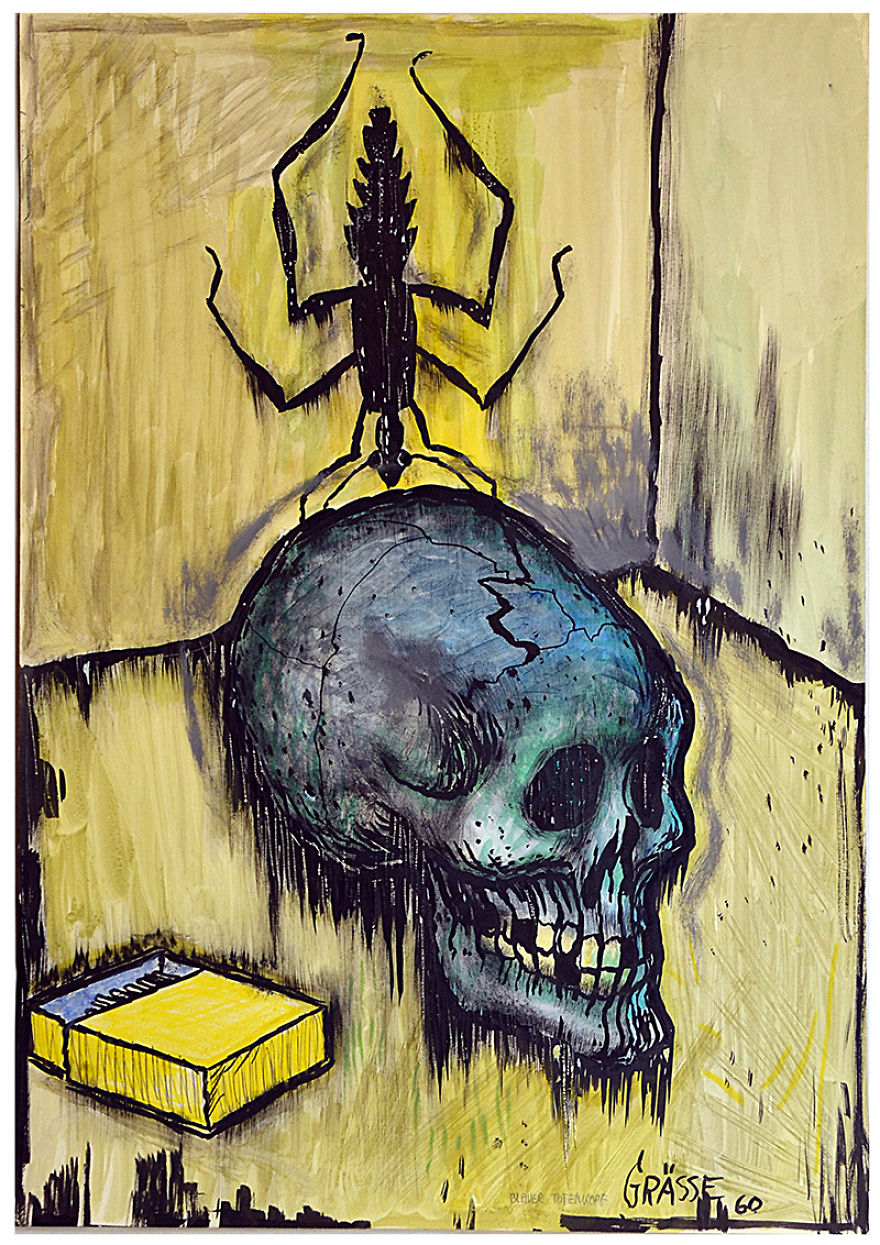

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) Untitled, Ink and acrylic on paper, 1960

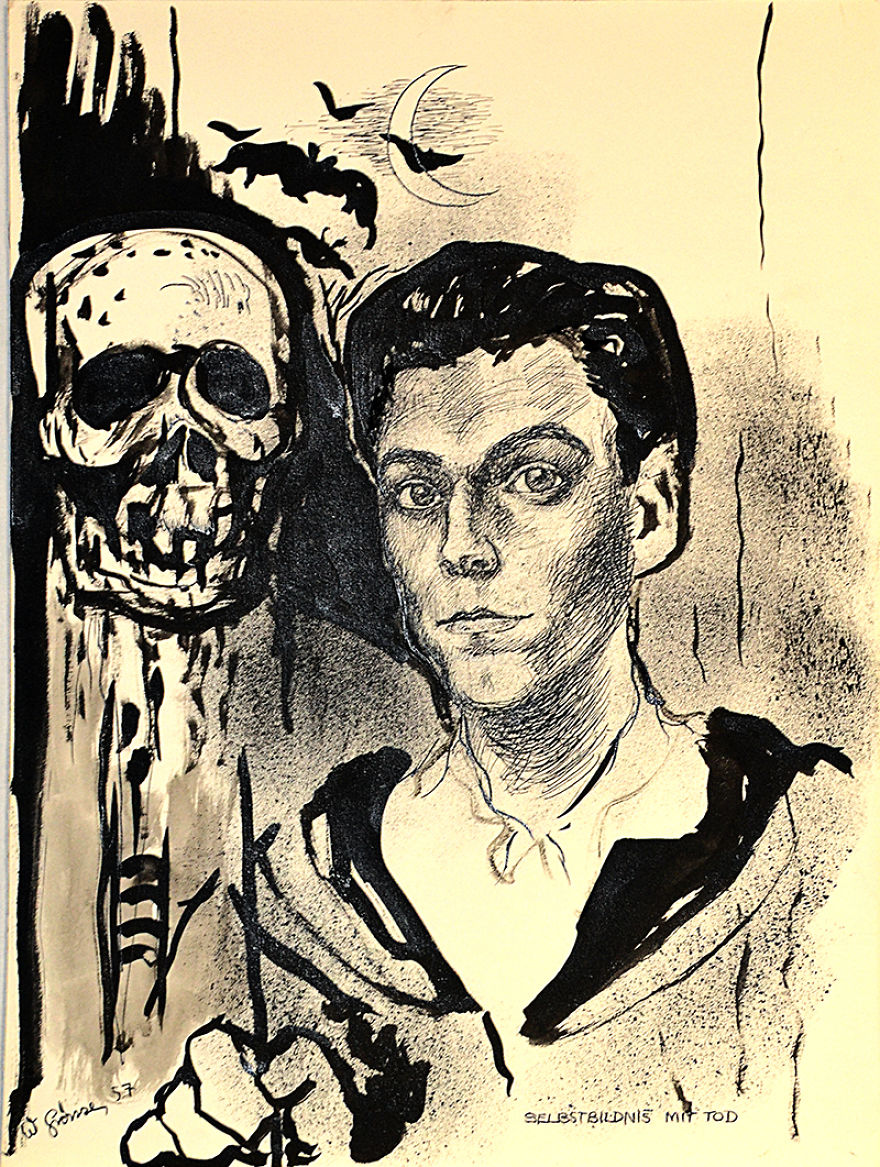

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Selbstbildnis Mit Tod” (Self-Portrait with Death), Ink on paper, 1957

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Luna”, Ink on paper, circa 1980

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) Untitled, Ink and acrylic on paper, 1960

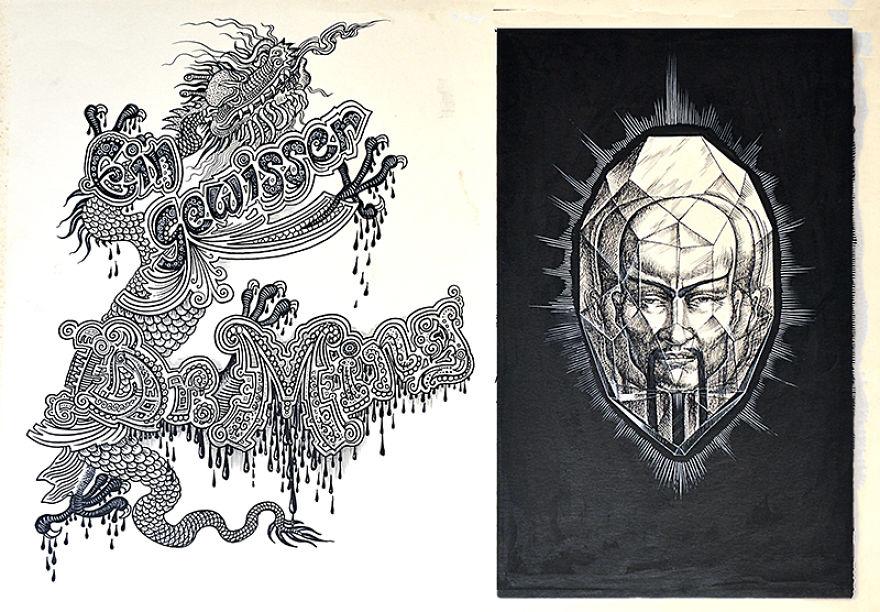

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Ein gewissen Dr. Ming” (A Certain Dr. Ming), Ink on paper, 1962

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Ein gewissen Dr. Ming” (A Certain Dr. Ming), Ink on paper, 1962

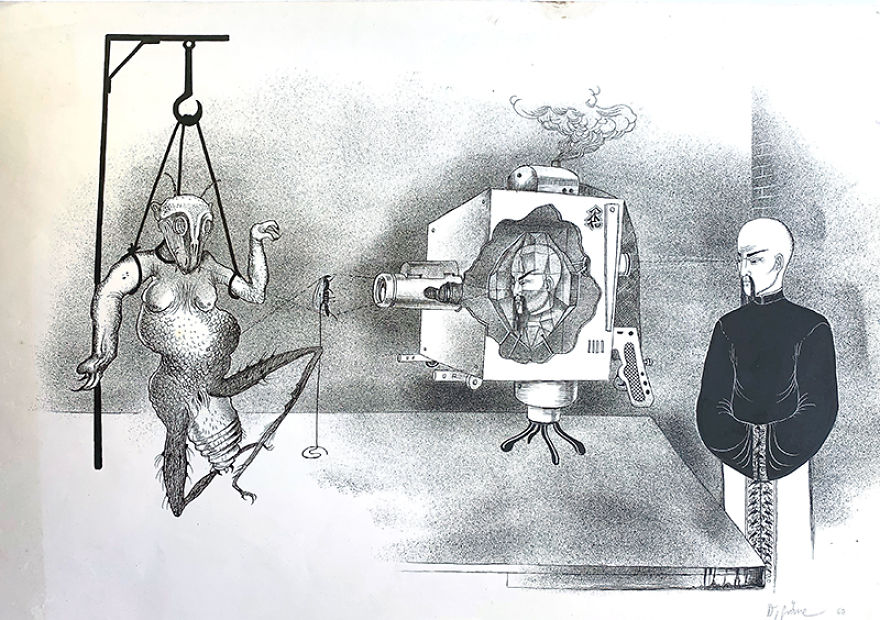

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Ein gewissen Dr. Ming” (A Certain Dr. Ming), Ink on paper, 1962

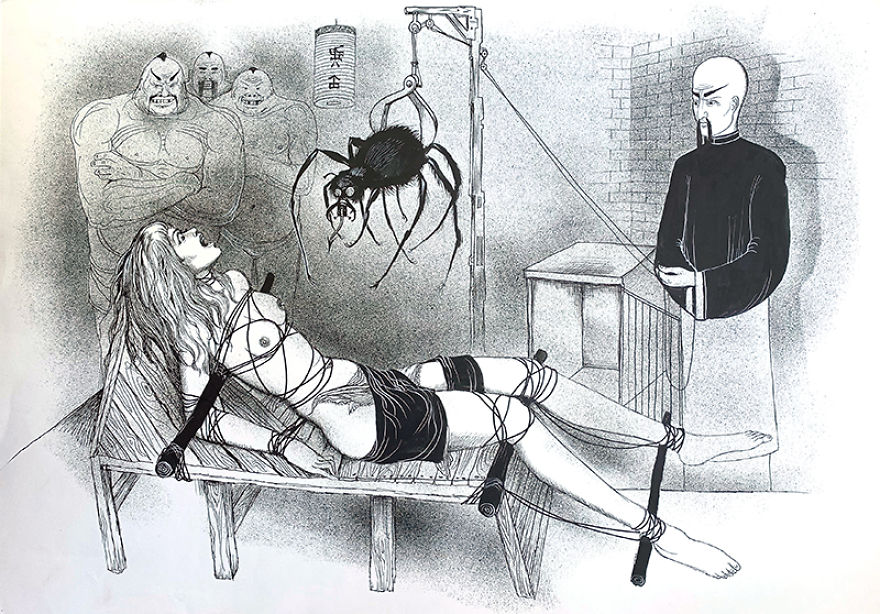

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Ein gewissen Dr. Ming” (A Certain Dr. Ming), Ink on paper, 1962

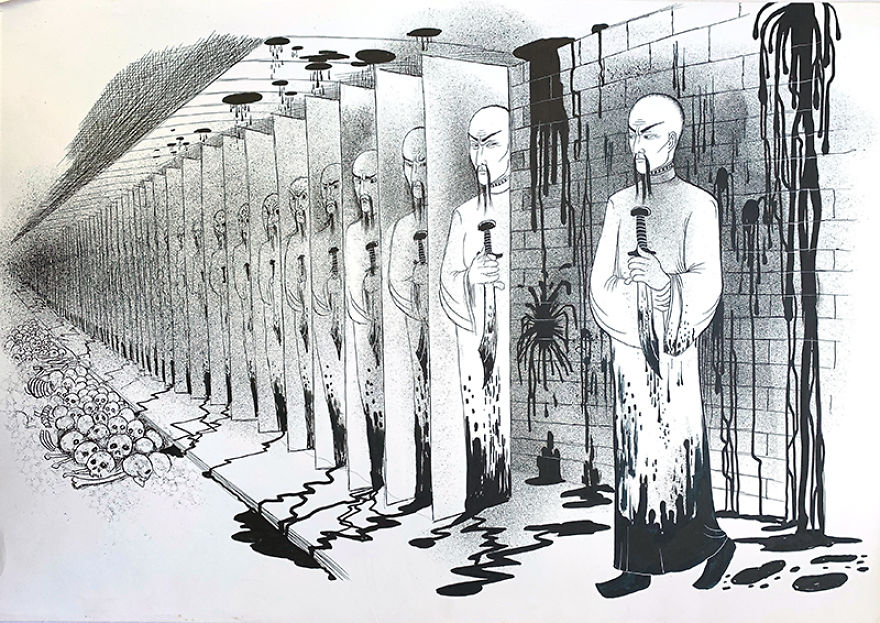

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “Ein gewissen Dr. Ming” (A Certain Dr. Ming), Ink on paper, 1962

Wolfgang Grasse (1930 – 2008) “The Broom” Ink on paper, 1984

461views

Share on Facebook

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

0

0