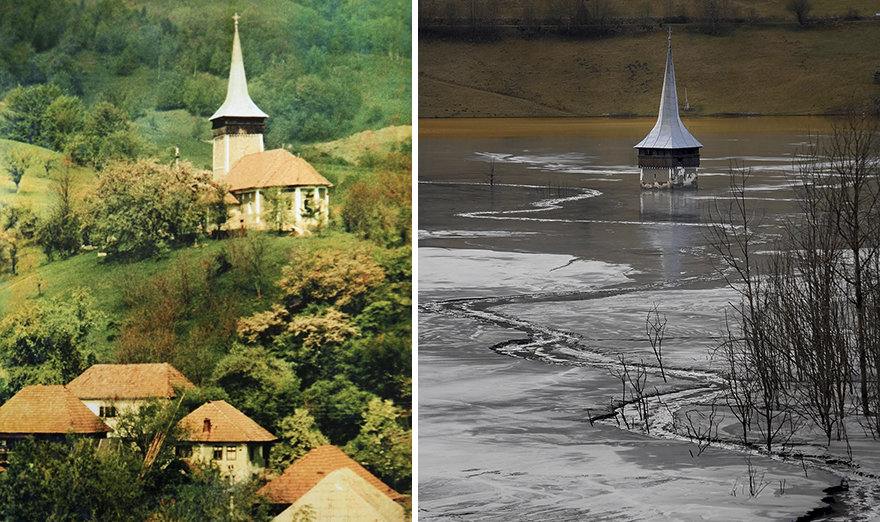

This Church Spire Is All That Remains Of A Village, Soon It Will Be Buried Completely

The village of Geamana once lay deep in a fertile valley, today it lies under 90 meters of toxic waste.

All 2017 photos Copyright Amos Chapple/RFE/RL. Archive images courtesy Cornel Holhorea.

More info: amoschapplephoto.com

40 years after the Romanian village was evacuated, me and a local photographer Ciprian Hord met some of the locals who refused to leave

We discovered it’s not just the buildings of this ghost town entombed under the mire…

Geamana in the early 1970s (yes, that’s the same church spire). Plans for extracting copper from a nearby mountain were already underway

In the spring of 1977, prospectors sent by the communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, arrived in Geamana and told locals to get ready for life elsewhere. The villagers were offered around $2,000 in compensation for their homes. Geamana’s 300 families then scattered throughout Romania…

Work at the Rosia Poieni mine began in earnest. This is the second-largest copper mine in Europe and employs around 500 people

Note the multi-colored toxic chemical-filled lake in the background, where the now-abandoned town once stood.

The same lake, with the mine in the top right of the drone picture

Once communist authorities built the dam in the foreground to seal up Geamana’s valley, a silty grey liquid began creeping through the lanes of the village. That’s their idea of waste management.

The slurry, which continues to slop into the valley today, is a result of “froth flotation,” a process used by most copper mines

It is this waste that drowned Geamana. The lake continues to rise, climbing the walls of the valley at the rate of around 1 vertical meter each year

Along with the slurry from the mine, some sections of the runoff lake have turned red from “acid mine drainage”

The acidic red water is a result of rain and spring-water running through the minerals exposed by the mine

The process occurs naturally, but mining intensifies its effect

But despite the inundation, not everyone left Geamana’s valley

Maria Prata is one of around 20 villagers who stayed, moving to higher ground as the lake rose

The 70-year-old says she spent her childhood in Geamana sleeping in a stable, “me on one side, the cows on the other.”

Maria Prata and her late husband photographed a few years before the prospectors arrived

She is surprisingly chill about the activity of the mine and the water pollution. “What’s done is done. The village is an abandoned place now. At least [with the mine here], the people have work.” But like other remaining villagers, she holds real bitterness for one promise that the communist authorities broke.

The villagers were assured that their ancestors’ graves would be relocated. It never happened

This graveyard was flooded only in the past few years. Many other graves lie deep beneath the slurry and are now virtually impossible to recover

Ana Prata tends to the grave that she will share with her husband, who died in 2012

It lies on a hill high above the lake, a precaution against the fate of Ana’s parents and grandparents whose graves lie entombed under meters of slurry.

Nicolae Turdean, the general manager of the Rosia Poieni mine, speaking with media at the runoff lake

He told us he knew nothing about the graves currently being submerged but said a church near those graves would be moved.

Turdean told us the villagers who remained in the valley after being given compensation “are living in our houses. But we tolerate the situation and will continue to tolerate the situation as long as they don’t affect the works around”

But the instagram fame of this site is bringing attention the state-run mine appears eager to dodge

Former Geamana local Cornel Holhorea told us the mining company had tried to demolish the spire of this church around five years ago

The work was canceled after an outcry from Geamana locals. But as the lake continues to rise, soon the last remnants of this village will be gone forever

37Kviews

Share on FacebookThank you amos for educating us all with this history. While employment of 500 workers is important, so is the altered lives of the villagers, destruction of the environment , & desecration of gravestones . There is no happy ending here.

Indeed, while the locals were incredibly sanguine about the loss of their village, the grave situation is horrible.

Load More Replies...I know similar stories, even here in Argentina. But the companies made it well, relocating the people in new houses in a new town. But the way they managed it here is very cruel.

It's so sad all that history. Sort of like Pompeii, were losing historical value and history. And it's being buried. Continued

Not by ash from a volcano but from water rising a meter or more a year.

Load More Replies...I have been there by bike, and the place is actually really eerie at night, the few locals told us to be wary about the wild animals ( mostly bears) that are around there, hence they're more aggressive than the ones from other parts of Romania. When I was there, the water wasn't red, but mostly normal water hue, add a bit of greenish, although it smells quite metallic.

I grew up there,my grandparents left Rosia when i was young.My best life memories are there,under that lake.Soon,they will start extracting gold from Rosia Montana but they already promised they will move the old church that is there and once they are finished they will grow back the nature and trees that they destroyed.As you can see in pictures,i don't think its gonna happend.Oh and btw,Romania wins only 4% of this deal...at least we have jobs

Very sad story of the industrialization of some land in order to extract the Earth's valuable contents (copper) but displacing people's entire lives by destroying their village....a genuine tragedy of mythic proportions.

Similar thing happend to Donji Milanovac, Serbia, because of the hydrocl power plant Djerdap, but town just were floded by Danube, there is no polution. Roof of the church you can also see stand out of wather

Almost every county from Romania has a similar village drowned on Ceausescu's orders, partly because of his mindless industrialization and partly because of his attempt to "systematize" the rural parts, (destroy and erase historical villages mostly with German and Hungarian inhabitants) of the country, mostly of Transylvania. Just check the stories of Bezidu Nou, Cinci-Cerna or Giurcuta de Jos.

And let's not forget Ada Kaleh. In 1970 a whole island enclave with a unique history was drowned beneath the waves of the Danube and it's 1000 inhabitants scattered to the winds.

Load More Replies...I'm so sorry, I'm very moved by this, and the story is very interesting and sad, but Did anyone else think of that one Scooby-Doo movie?

I did! I was thinking the same thing, why was this down voted?

Load More Replies...Awww thank you for that...a kind of eerie silence is there I should think.

Thank you amos for educating us all with this history. While employment of 500 workers is important, so is the altered lives of the villagers, destruction of the environment , & desecration of gravestones . There is no happy ending here.

Indeed, while the locals were incredibly sanguine about the loss of their village, the grave situation is horrible.

Load More Replies...I know similar stories, even here in Argentina. But the companies made it well, relocating the people in new houses in a new town. But the way they managed it here is very cruel.

It's so sad all that history. Sort of like Pompeii, were losing historical value and history. And it's being buried. Continued

Not by ash from a volcano but from water rising a meter or more a year.

Load More Replies...I have been there by bike, and the place is actually really eerie at night, the few locals told us to be wary about the wild animals ( mostly bears) that are around there, hence they're more aggressive than the ones from other parts of Romania. When I was there, the water wasn't red, but mostly normal water hue, add a bit of greenish, although it smells quite metallic.

I grew up there,my grandparents left Rosia when i was young.My best life memories are there,under that lake.Soon,they will start extracting gold from Rosia Montana but they already promised they will move the old church that is there and once they are finished they will grow back the nature and trees that they destroyed.As you can see in pictures,i don't think its gonna happend.Oh and btw,Romania wins only 4% of this deal...at least we have jobs

Very sad story of the industrialization of some land in order to extract the Earth's valuable contents (copper) but displacing people's entire lives by destroying their village....a genuine tragedy of mythic proportions.

Similar thing happend to Donji Milanovac, Serbia, because of the hydrocl power plant Djerdap, but town just were floded by Danube, there is no polution. Roof of the church you can also see stand out of wather

Almost every county from Romania has a similar village drowned on Ceausescu's orders, partly because of his mindless industrialization and partly because of his attempt to "systematize" the rural parts, (destroy and erase historical villages mostly with German and Hungarian inhabitants) of the country, mostly of Transylvania. Just check the stories of Bezidu Nou, Cinci-Cerna or Giurcuta de Jos.

And let's not forget Ada Kaleh. In 1970 a whole island enclave with a unique history was drowned beneath the waves of the Danube and it's 1000 inhabitants scattered to the winds.

Load More Replies...I'm so sorry, I'm very moved by this, and the story is very interesting and sad, but Did anyone else think of that one Scooby-Doo movie?

I did! I was thinking the same thing, why was this down voted?

Load More Replies...Awww thank you for that...a kind of eerie silence is there I should think.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

206

27