Hey Pandas, What Do You Think Of A System That I Created?

So, I am a philosopher. I created this ethical system, and want to know what people think about it. I’ll note that there’s some background info on other ethical systems, which makes it a bit long. Thank you for taking the time to read it, it means so much to me. So without further ado, here it is:

(I’ll also note that it isn’t done yet)

Virtuism: An Overview

“Virtue is the golden mean between two vices, the one of excess and the other of deficiency.” — Aristotle

Life is filled with moral dilemmas. That’s simply a fact. And everyone has different opinions as to how to solve them. One person might say the answer is whatever brings the most overall happiness. Another may say that it’s about following moral duties and laws. Yet another says it depends on your motive. So then how can one know what to do? That is a point of great contention among philosophers and theologians, and anyone concerned about the great questions that we humans strive to know and understand. And the question is made harder by our not knowing if morality is even something that is objective among people or if it’s relative depending on the culture or even the individual. Add that to the question of whether life has any inherent meaning, and you have infinite answers, or perhaps even no answers to the question of how to solve these dilemmas.

But these dilemmas are crucial to becoming good people. Because we’re shaped by our choices. We become who we decide to be through our actions. They shape us. If you choose the honest action in a hard dilemma, you will become more honest outside of these dilemmas. But if you justify selfish actions in the dilemmas, you will begin to justify any undesirable action. And so it’s essential that we make the right choices in situations where there aren’t any good options.

And it’s not just choosing whether you’ll eat ice cream or cake. (Although, if you ever find yourself in such a situation, always go for the ice cream-cake) Usually, these choices have real-world repercussions that affect not just you, but others as well. So it’s crucial that we make the right choice.

And one thing to clarify- when I say the right choice, I don’t mean some universe-ordained laws. I just mean whichever choice is most practically wise. While objective moral laws can be dismissed depending on your opinions and beliefs, they don’t negate the existence of a right choice. Moral laws or not, there is always a more preferable decision. Which decision simply depends on whatever ethical system you follow. All that is to say the phrase right choice does not mean that I am prescribing an objective set of laws for you to follow, but that you will often come across dilemmas in which you must make a choice, and that everyone has a different idea on what the best option is. But if the right choice bothers you still, mentally replace it with a better option.

So everyone has their idea of the right or more preferable solution to these dilemmas. And making the right decision is essential to not only becoming the person who makes the right decisions, but also the decision that doesn’t harm others more than necessary. And which of these you find to be more important depends on your view of things, and we will get to that.

We call these ideas on how to find out the right thing to do ethical systems. Ethical systems are moral codes or mantras or ideas that give you an idea of what to do in a situation where you have to choose between two options that both have repercussions that affect other things.

But first, let’s define these ideas of the right thing to do, and maybe root out a few of their flaws. So I’ve separated these ideas of what the right thing to do is into two categories of ethical systems.

There is the Absolute category, and the Adaptive category. The Absolute category is made up of every ethical system that revolves around moral laws or codes. Absolute systems say that there is a rule or a few rules that you should follow in these dilemmas, and that rule leads you to do the right thing, even when it’s hard. Everything in the Adaptive category revolves around context and situational differences. Adaptive systems say that every situation is different, and that you should take into account some reasoning about the choices.

So we’ll start by calling out the strengths and flaws of the Absolute systems.

The Absolute systems have many strengths and many weaknesses. They all revolve around the idea that morality is a fixed concept that we just need to act on. They believe that in every situation, every dilemma, there’s a rule that will show you the answer. They are unbiased and often just, but also strict and rigid.

One great example of an Absolute system is Deontology.

Deontology

Deontology is the idea that there are certain moral laws in place, and that it’s our duty to follow those laws. I don’t get any special treatment because I’m me, and you don’t get any special treatment because you’re you. So these laws are fairly straightforward. Don’t kill people, don’t steal things, don’t lie… you get the idea.

But what determines if something is a moral law? Immanuel Kant, the creator of Deontology set some clear guidelines.

First, it has to be universal. Think about the Golden Rule, do to others as you would have them do to you. Kant repeats the statement, only making it more pretentious, saying “Act only on the maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it become universal law.” So, it basically says that whatever you do, you should be able to make it a universal law. So if I give to the poor, I’m saying that everyone should give to the poor. But if I steal, I’m saying that everyone should steal.

Second, it must respect people as people. The terms that Kant used was ends in themselves. What that means is that you are not allowed to use people as a means to an end, or to put it into understandable terms, use people as pawns to achieve your goals. You must treat people as their own ends instead of using them for your ends.

So it’s great for not justifying everything you do. But that’s also its downfall.

See, consider in your head, Robin Hood. He stole from the rich and gave to the poor. Great guy, right? Isn’t that obviously a good deed? Most of us would think so. But not a deontologist. A deontologist would say that stealing is wrong, and that while giving to the poor is right, and maybe even a moral duty, it is unacceptable to be stealing in order to do it. One rather ridiculous thought experiment meant to out the flaws of deontology is that of the neighborhood serial killer.

Let’s say that you’re at home, and your family is down the street. You hear a knock on the door. You open it and standing there is a man holding a chainsaw. He tells you that he’s the neighborhood serial killer and asks that you tell him where your family is, as he’d like to slaughter them. Unless someone just really hates their family, they would obviously lie about where their family is. But a deontologist couldn’t lie to the killer, as lying is wrong.

One thing to note is that a Deontologist says that lying is wrong. What a deontologist may do in that situation is twist the truth to misguide the killer. They may say “A few hours ago, my family was at the store. You could check there.” Now, if their family was at the store a few hours ago, the deontologist would not be lying. Therefore, they can not only prevent lying but also protect their friend.

Now, there are a few responses to this, namely that it’s not super easy to twist the truth unless you are very good at quick thinking. But regardless, deontology may offer a way to prevent justification of bad things, but it may not always lead to the best outcome. Which brings us to the next Absolute system.

Utilitarianism

There’s some debate as to whether Utilitarianism is an Absolute system or an Adaptive system, but I would call it an Absolute system because you must follow the rule, whether you think it’s right or not. But regardless, Utilitarianism is a popular way to solve problems because of the clarity and simplicity of it. Essentially, Utilitarianism is a system that says that you must do whatever brings the most utility to the most people, and the least suffering to the least amount of people. So the answer to a dilemma is to turn it into a math problem. Very straightforward.

The biggest difference between Utilitarianism and Deontology is that while Deontology focuses on the motive of the person, Utilitarianism focuses solely on the outcome of the action. This has often had them in opposite categories, such as the most common outcome-based versus motive-based.

Created by Jeremy Bentham and refined by John Stuart Mill, classic Utilitarianism focuses on maximizing utility; or maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering.

Utility is essentially happiness, pleasure, goodness… things that people want to feel. If I’m happy, my utility is high. If I’m unhappy, my utility is lower.

But let’s take a moment to consider the downside to Utilitarianism. Let’s imagine that you’re a doctor and you have five patients that are all in dire need of a different organ or they will die. But alas, you don’t have any organs to transplant. Now, you have another patient napping in the other room who’s just here for his regular check-up. He’s perfectly healthy. You can technically kill him and harvest his organs to save the five people. Now, most people would say that they wouldn’t do that. But, a Utilitarian, if following their moral laws, would have to do it.

Absolute Systems Overview

There are many more different kinds of Absolute systems. I won’t give a thought experiment for each and every one, but I’ll briefly explain some of the more popular ones.

•Divine Command Theory – Morality is given to us by God, and it’s absolute.

•Natural Law Theory – Morality is based on human nature and reason, so it’s our moral duty to preserve life, eat, etc.

•Any flavor of Utilitarianism where you’re maximizing _____ (Maximizing choices, minimizing suffering, maximizing knowledge, etc.)

•Libertarian Ethics – Freedom is the ultimate good, and restricting freedom is immoral.

•Moral Platonism – Objective morality exists as abstract Forms and it’s our job to find it.

There are many more systems, but I’m not going to go over them all. But in summary, the trademarks of an Absolute system are that it revolves around moral laws or duties, and that you must always act on those duties.

Pros to this mindset:

Clarity- you can always know what to do in a situation, which makes it appealing.

Objectivity- you can’t make exceptions for yourself, and you can’t justify things that may not be moral.

Great for Governance- It works exceptionally well when crafting legal and social structures, as nobody is exempt from the moral laws.

Encourages Integrity- Promotes responsibility and ethical behavior.

Cons:

No Context- Most real-life dilemmas have all sort of complications and nuances. A decision will affect a lot more than just some thought experiment.

Rigidity/Dogmatic- It’s not always as simple as just following rules when there’s people involved. For example, imagine that you can save five strangers, and kill one. But now imagine that the one person (or one of the five, depending on what system you’re using) is your best friend. Now it’s a bit tougher. Because at that point, morality being a math problem isn’t such a nice thing.

Harsh- Again, not enough context to make the best decision. It could punish a starving child for stealing food or justify discrimination.

Often Leads to Hypocrisy- With such strict rules, it’s difficult to stay true to them all of the time, leading to you preaching about never lying and then doing it.

So, Absolute systems are perfectly fair and great for giving clear answers, and great for preventing justification, but they struggle in the field of looking at the context of a situation or adapting to changing circumstances.

Adaptive Systems

Adaptive systems are just that. Adaptive. Their defining feature is that they believe that morality isn’t fixed. They think that the right thing to do in a given situation is dependent on that given situation. They’re great at avoiding the problems with the Absolute systems, but they have problems of their own. Let’s take a look at some Adaptive systems.

Virtue Ethics

Virtue Ethics is a system about… you guessed it, virtue. Instead of saying what rule applies to this scenario, they ask what a virtuous person does in the scenario. So instead of calculating maximum amount of good the choice brings, you say what would a wise, courageous, compassionate… etc. person do in this situation?

Devised by Confucius and Aristotle in their respective traditions, this ancient system has had more big names in modern times.

So let’s imagine that you are in the famous Trolley Car Problem.

You’re standing next to a train track, by one of those levers that change the direction of the track. As you stand, you notice that after the track forks, there are five workers on one track. On the other, there’s one other worker. Suddenly, you hear a train coming. Upon realizing that the brakes are out, the driver of the train has passed out. The train is speeding towards the track with five workers on it. But as you watch, you remember that you’re standing next to the lever. You can pull the lever and switch it to the other track, killing only one person. What do you do?

This is a very popular dilemma among thinkers. If you let the train go along its route, five people will die. But you won’t have killed them. If you switch the track, you’ll have killed somebody. But you’ll have saved five. A Utilitarian would obviously kill the one. A Deontologist may not, as killing is always wrong.

But a Virtue Ethicist is faced with a challenge. What would a virtuous person do? In such a situation, would they really have time to consider such a thing? And if they did, it’s still up for debate what the most virtuous decision is.

A Virtue Ethicist may say that you would have already invested time in becoming a virtuous person, which is the other part of Virtue Ethics. They want you to be cultivating virtues every day, so that you will make the right choice when you are pressed to do so.

Now each Adaptive system is much more different from each other than each Absolute system, so I’m going to list the pros and cons of each system.

Pros and cons of Virtue Ethics:

Pros:

Flexible- You aren’t bound to any rules, so you can make the decision you feel is right.

Encourages Moral Reasoning and Balance- encourages you to practice virtues and be a good person.

Cons:

Requires That You Already Be a Moral Person- if you’re a selfish and immoral person, there’s really no point.

Can Justify Anything- This one will apply to many of these systems. You can justify any action you do, which can lead to immoral decisions.

Situational Ethics

Situational Ethics is a system of love and context. The main idea is that what the right thing to do is depends on the situation. The only string attached is that love is the only rule. Now, the fact that there’s a rule may make it seem Absolute, but it’s really more of a hybrid system. But I would call it Adaptive simply for its idea of the right thing to do being relative to the situation. So it is still Adaptive. And Situational Ethics is really quite appealing. But there’s one issue. Love is vague. A parent that extremely harshly disciplines their child may say they did it out of love, in the same way a parent appalled by such extreme discipline doesn’t do that out of love. So Situational Ethics works only with another system as a guideline.

Let’s take a look at an issue with Situational Ethics.

Say a criminal is on trial. The judge is a kind, merciful person, and he lets the criminal off with a light sentence. The criminal serves his time, but once the criminal is free, he commits more crimes and harms more people.

Now, you might say that wasn’t the fairest example, and it wasn’t. But that just goes to show that love is such a vague concept that it’s hard to define it. I mean, let’s consider the Trolley Car Problem. Do you pull the lever or not? It would be a loving thing to do to save five people. It’s also a loving thing to do to not kill someone. So what do you do? Situational Ethics is not enough to make a decision, because love can mean so many different things.

Pros and Cons:

Pros

Flexible- Leaves more room for context and nuance.

Avoids Moral Absurdities- Avoids doing something wrong for the sake of following rules.

Cons

Inconsistent- Two people in the same situation may make completely different choices.

Prone to Bias- Can justify selfish choices under the guise of love.

Moral Relativism

Moral Relativism is an increasingly popular theory, which says that there are no moral truths, and that what’s right depends on the culture or the person. So the Romans having slaves kill each other in an arena in the name of public spectacle? It’s okay, because that was acceptable in their culture. Slavery and racial discrimination? It’s wrong now, but that’s just the way it was back then.

So it’s great for being culturally sensitive and open-minded to other people’s ideas, but it also leads to justifying awful things and herd mentality.

Let’s take a look at how this mindset works by imagining we’re a time traveler, so we get to travel back to all sorts of times in history. And we are Moral Relativists, so we don’t judge people unfairly from out modern perspective. So we travel back to Ancient Sparta. We walk around for a bit, and we see a few families abandoning their children. We go up to them and we begin to protest. You may say that leaving children to die is awful. And they say, “Not in our culture. Here, strength is everything, and they were weak.” So we must remind ourselves that morality all depends on the culture, and we move on.

Next, we go to Nazi Germany. We see police officers putting Jewish people and homosexuals and people thought to be guilty of treason into concentration camps. We know from learning history that most of them will die there. But we couldn’t protest, because that was their culture.

Next, we go to the future. And in that future, we get arrested and put into jail for being time travelers. You might try to protest. But someone will tell you that in their culture, the lives of time travelers aren’t worth the same as a normal person. So we must reluctantly admit that it’s fine.

Now, that was a branch of Moral Relativism known as Cultural Relativism. The other branch is Individual Relativism, which believes that morality is up to the individual. So if a Spartan or a Nazi believes in abandoning children or killing Jews, then an Individual Relativist would have to say that it’s okay. They may disagree themselves, but they can’t judge.

Now, there’s also a more universal option which is called Soft Relativism. Soft Relativists believe that there may be some universal truths, but different cultures define them differently. So they might say that slavery is wrong, but they didn’t know that back then. This option is more balanced, with the Relativist sensitivity and non-judgement, but still recognizing that it isn’t correct in our modern knowledge.

Pros and Cons

Pros:

Culturally Sensitive- Avoids judgment on other cultures that we may not agree with.

Open-Mindedness- Avoids the belief that your way is the only way to do things.

Cons:

Herd Mentality- If you are supposed to act like your culture does, you end up doing just that instead of identifying flaws in the cultural system.

Justifying Atrocities- You can justify anything from lying to genocide by saying that morality depends on the person.

Inability to Change Things- If you don’t like a certain aspect of culture, then you can’t do a whole lot to change it if culture is fine as it is. Imagine if Martin Luther King Jr. was a Relativist. People would still be segregated because he thought that that was just the culture.

Adaptive Systems Overview

So Adaptive Systems are great for avoiding the problems with Absolute systems, namely inflexibility and lack of context in decision-making. The systems that we have covered aren’t the only Adaptive systems. Some other popular ones are:

Pragmatism- The best choice is whatever works best in practice. Somewhat similar to Utilitarianism, but more relative to the situation, and requires some result that you want to achieve to see what achieves that.

Care Ethics- Do the loving thing. Morality revolves around caring for other people above all else, especially caring about the people that you love.

Existentialist Ethics- There are no inherent moral rules, and morality revolves around being authentic and making your own meaning.

Pluralism- No moral _____ (consequence, virtue, etc.) is inherently better than others, but some work better than others in certain situations.

So those are most of the popular systems are great for some things, but they also have problems. They make it very easy to justify anything. They are too much on the opposite side from Absolute systems. So let’s re-examine these good and bad parts.

Pros and Cons

Pros:

Context- allows better insight into decisions because they rely on each situation being different. Like how a starving child stealing food is different from a millionaire stealing for fun.

Encourages Critical Thinking- While Absolute systems can lead to complacency, Adaptive systems require you to consider moral issues so as to decide what the best option is instead of blindly following rules.

Allows for Moral Progress- Allows for progression in how we see morality, like the civil rights movement and such. Moral laws and Absolutes can make excuses for why that was always right but can’t progress well.

Cons:

Justification is Too Easy- You can justify any action in an Adaptive system. A dictator can come to power by saying that the people need stability, and stability is ______ (Virtuous, Loving, etc.)

Difficult to Enforce- Justice is not easy in an Adaptive system, because everyone has different opinions on how to handle something. One judge can give one sentence, and another can give the opposite.

Requires Pre-goodness- If you are following an Adaptive system in hopes of being as moral as you can, you must have already cultivated virtues so as to avoid justification and acceptance of awful things. So it’s a great system for someone who’s already virtuous, but it’s very easy for someone who has selfish intentions to adopt one of these systems to justify things.

So Adaptive systems can solve a lot of the problems with Absolute systems, but they raise quite a few problems of their own, namely lack of any clear rules to follow.

So what is the right system?

Both Absolute and Adaptive systems have problems. Most people who are actually concerned with ethical systems just pick the lesser of the evils. Someone may choose deontology because they feel that it’s better to follow rules than justify bad things. Another may choose Relativism, because it’s best to accept people than judge them. But as we’ve examined the pros and cons of each system, you may be feeling as though you don’t really like any of the options. That all of them have appealing aspects, but none of them really feel right.

I felt the same way. I liked Virtue Ethics, and I understood the appeal behind Utilitarianism and Situational Ethics, but none of them felt like they were the right system to live by. So I devised a system that combined the great things of the Absolute systems and the great things of the Adaptive systems.

Virtuism

Choices of morality can be seen like a little scale inside of our prefrontal cortex. If we follow Utilitarianism, the scales are constantly moving, weighing the maximum happiness. If we follow Deontology, then the scales are always tipped to the side of the rules. If we follow Relativism, our scale is just a copy of whatever our culture says or whatever we want. So when we make a choice, our scale moves in accordance with our subconscious ethical system, whether we believe we have an ethical system or not.

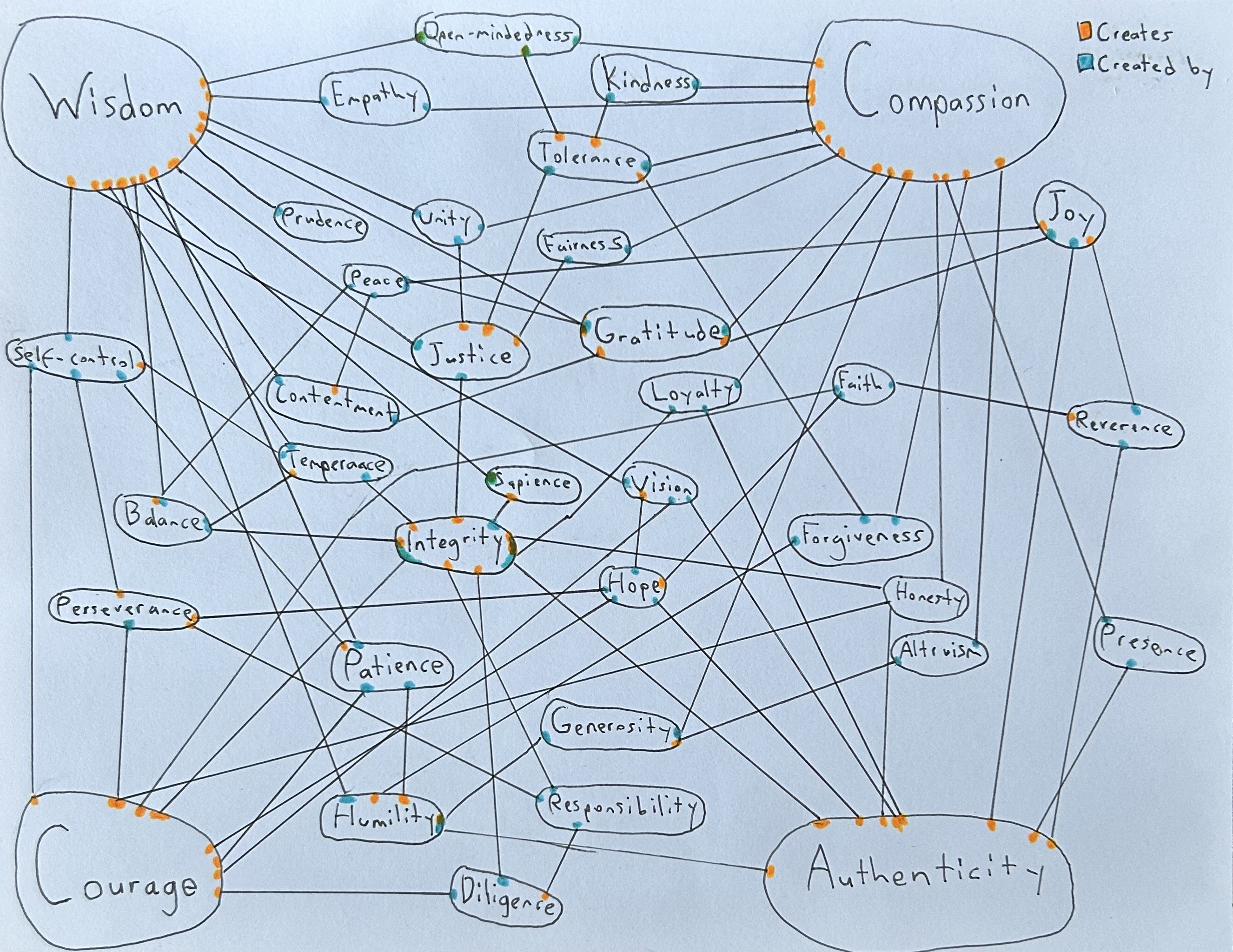

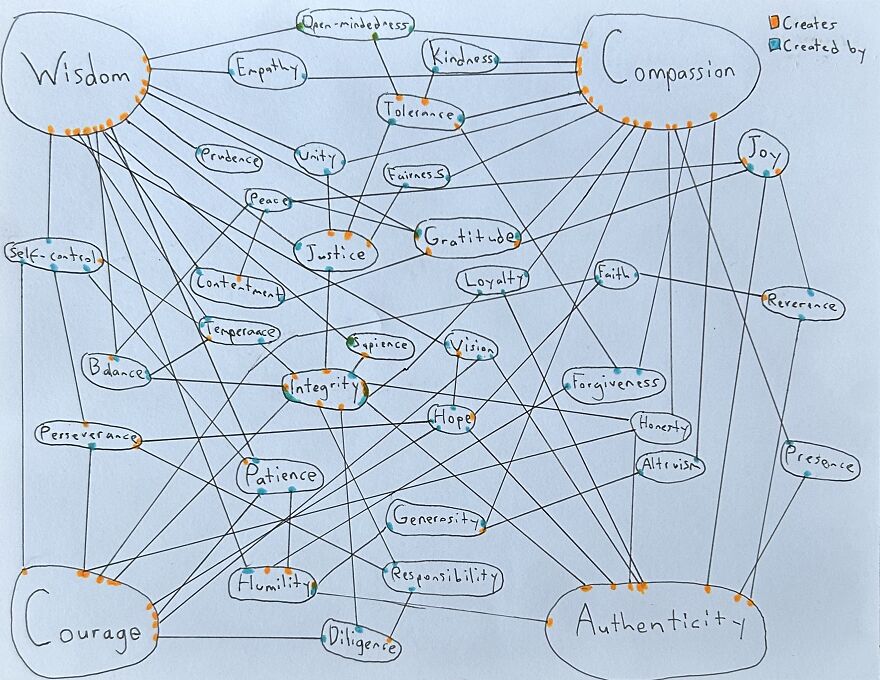

So my solution could be seen as a combination of Virtue Ethics and Utilitarianism, and also some Situational Ethics and Pluralism. The general idea is that whenever we’re faced with a dilemma, we weigh which virtues we use in the choice instead of happiness, and which vices instead of suffering. This is the concept:

Step 1: Identify the Outcomes

We must first identify the most likely outcomes for each choice. The purpose of this is to prevent justifying your actions by adding irrelevant virtues. Not as if we’re just theorizing about what any outcome could be, but things that we can clearly see. For example, in the Trolley Car Problem, the outcomes that we can identify are either five people die and you aren’t necessarily responsible for those deaths, or you killed one person and five people didn’t die. Simple things like that. Once you can identify the outcomes, you can move on to the next step.

Step 2: Identify the Virtues & Vices

Once you have the outcomes, you look at those and determine which virtues each outcome contains. For example, imagine that your friend just got a new haircut, and it is atrocious. It’s so bad that it’s probably considered a war crime in several countries.

Well, that’s a bit of an exaggeration, but anyways, his haircut sucks. He asks you what you think about it. Do you be honest and tell him that it doesn’t look good and hurt his feelings, or do you be polite and lie? The answer lies in weighing the virtues. Once you identify the outcomes, you must figure out which virtues and vices come with each outcome. For example, if you choose to be honest, the most likely outcomes are you were honest and didn’t lie, and your friend is upset and offended. So then you have to find out which virtues and vices go with those outcomes. So for the virtues, you’ve got honesty, courage, and authenticity. For the vice(s), you’ve got harshness/bluntness. For lying to protect his feelings, the outcomes are you lied, lying is wrong, and your friend’s feelings aren’t hurt. The virtues are kindness, compassion, empathy, and prudence. The vice(s) is dishonesty.

Step 3: Add the Virtues & Vices Up

So, then you add up the virtues and vices on each side. Each virtue counts as +1, and each vice is -1. So when we add up the grand totals, the side of being honest has 2 (three virtues minus one vice), and the side of lying has 3 (four virtues minus one virtue). Therefore, you should lie. But wait. There’s more.

(Optional) Step 4: Reevaluate

And then there’s more. If you dislike the answer given by Virtuism, you can and should find a better middle ground. If you don’t want to lie to avoid hurting your friend’s feelings, you can try to come up with a better option that has more “net virtue” than the previous. For example, you could be tactfully honest, and say something that isn’t brutally honest, but makes him second-guess his choice of haircut. There’s never a dichotomy of choice in real-world situations. It’s only either-or when it’s a crafted thought experiment.

So those are the steps for Virtuism. Let’s try out another dilemma to see how it works and explain it better.

The Whistleblower

You are working at a corporation when you discover that your boss and several other top executives is involved in several illegal activities, including stealing money from the company. You know that if you report it to the authorities, then the company will go bankrupt, and many employees that don’t know anything about the crime will lose their jobs. But you also know that it’s wrong to let it happen. What do you do?

So how do you figure it out? You probably know what you would do, but let’s weigh the virtues and vices. of each choice.

First, the outcomes. If you report the executives, they will be held accountable for what they did and they won’t be able to continue their illegal activities. But it could also result in many employees that didn’t know anything about the illegal things losing their jobs if the company bankrupts.

If you choose to stay silent, the executives will keep stealing money and won’t be held accountable, but your coworkers will keep their jobs. (Unless someone else reports it.)

Next, the virtues and vices:

Report the boss: Virtues: Courage, Justice, Integrity, Honesty, Accountability. Vices: Ethical Rigidity (Doing the right thing regardless of the consequences.)

Do nothing: Virtues: Compassion, Empathy, Loyalty, Forgiveness. Vices: Cowardice, Injustice, Complicity (in the illegal activity).

Final Scores: Report the executives: 5. Stay silent: 1.

So in our little mental scale, reporting the boss outweighs doing nothing by a lot. Therefore, we should report the boss. Pretty straightforward, right?

This can be applied to any dilemma, and you can always seek a better solution if one seems wrong, so long as you are following the system.

Still doubting? Let’s look at how Virtuism solves the problems with other systems.

Context- The simple act of having to decide which virtues are relevant acknowledges context. While Deontology or Utilitarianism has a set code of things you’re trying to do, Virtuism’s use of virtues makes the process of decision-making different in every situation, allowing for more context.

Rigidity- Virtuism gives enough Adaptive to combat this through the ability to come up with a better solution if you don’t like the original, which allows you to escape the rigidity of other rules-based systems. If the worse outcome is the one chosen because of a virtue that’s hardly relevant to the situation, you can come up with an option that scores higher.

Justification- It’s much harder to justify an un-virtuous action if you first identify the outcomes and then weigh the virtues and vices of each side. Virtuism gives just enough Absolute mentality to prevent justifying things like the Adaptive systems often fall into.

Difficult to Enforce- Virtuism is a great way to decide on court cases and laws, because virtue is more or less universal. Nobody dislikes the idea of virtues such as wisdom or courage. They just prefer their idea of virtues. But regardless, weighing virtues is the best way to make and enforce the laws.

Dark Mode

Dark Mode

No fees, cancel anytime

No fees, cancel anytime

0

0