American Walks 20 Hours To Escape Ukraine, Shares “The Worst Night” Of His Life In A Viral Twitter Thread

Interview With AuthorWe all know how it goes: some malevolent, egoistic dictator declares war, all hell breaks loose and innocent people start fleeing to safety. Entire nations, some more than others, are used to this by now as history seems to be plagued by endless conflicts. One of them is currently happening in Ukraine, as more than 500,000 citizens were forced to abandon their lives and seek safety in neighboring countries.

The reality is, these treks, however hopeful, are no less of a collective nightmare than the actual atrocities waiting for refugees at home. Families are separated, people are trampled upon or lost to oceans. Finishing his two-week self-funded journalistic coverage of the unimaginable horrors in Ukraine, Manny Marotta, an independent journalist from Pittsburgh, US, documented and shared his “hellish 20-hour journey” to the safety of Poland on his Twitter feed.

A Twitter thread of Manny Marotta, an independent, self-funded journalist from Pittsburg, US, went viral after he shared his 20-hour trek from besieged Ukraine to Poland

Jorge Ramos, an award-winning Mexican and American journalist, once said: “My only advice is, follow your dream and do whatever you like to do the most. I chose journalism because I wanted to be in the places where history was being made.” Intentionally or not, the 25-year-old Pittsburgher took this advice to heart as Manny, who spends his days as a tour guide at the Carnegie Museum of Art, left everything and decided to take his chances of becoming “the first Western journalist to cover the Ukrainian refugee crisis” — something that he managed to achieve, no matter the cost.

“To be completely honest, I did not expect that Putin would actually invade Ukraine. I did not expect war, and the fact that it happened — took me and the rest of the country by surprise,” Manny told Bored Panda from his hostel room in Przemyśl, Poland. Despite the cries of his parents, who begged the boy not to throw himself into a lion’s den almost 5,000 miles away from home, Manny traveled to Kyiv, later relocating to Lviv, where he experienced the unimaginable horrors of war first-hand.

“Around seven in the morning, I woke up to the sound of air-raid sirens. I was a little confused at first and within the first hour, everyone knew what was happening,” Manny shared, adding that it was a bit “naive” and “almost foolish” of him not to expect to experience it. That’s when he decided it was time to leave the country.

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

One of the more horrific sights includes seeing how young men were separated from their families and forced to take up arms

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Just like hundreds of thousands of native families who had no other choice but to flee from danger, with numbers increasing tenfold every day, Manny hoped his plans wouldn’t turn into a refugee story. But he always considered it as a possible turn of events at the back of his head.

“The walk was part of an escape plan in case everything else failed. If I was unable to get a train or a bus, or any other means of transportation, I would have to walk,” he explained. Manny expected normal ways of transportation to be disrupted as the Russian invasion intensified. So he moved to the border town of Lviv, “Ukraine’s haven in the west,” as it’s been called by the media, and “was mentally and logistically prepared to walk.”

Some friendships bloomed and perished within minutes

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Manny was surprised to see so many people, young and old, willing to risk everything to reach safe haven in Poland

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

After the “longest and worst night” of his life, the young journalist finally reached his destination and was greeted with open arms

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Image credits: UkraineLive2022

Throughout his 20-hour trek from Lviv to Poland, which he documented on his Twitter thread as soon as he had access to the internet, Manny saw many things that would otherwise not be seen by many — including terrified babushkas and the conscription of young Ukrainian men trying to escape the war.

One of the befriended people Manny remembers from his journey is a 24-year-old Ukrainian, Maxion (or Max for short). Like many, he was forced to take up arms and turn back to defend his besieged country. “I spoke with civilians, mothers, children — they were all fine. But pretty much every man to whom I spoke with eventually was conscripted and did not make it through the border,” he said.

“At the time of interviewing Max, we spotted soldiers saying every man needs to leave the line.” Manny says the “utter disbelief” on Max’s face will be ingrained in his mind for a long time. Just like the rest of the families who left their brothers and fathers on the other side of the border, he had no idea what fate was waiting for his friend. “Two days ago, I received a message from him on Instagram,” Manny told. “He only let me know that he’s safe and not in the middle of the war with Russians.”

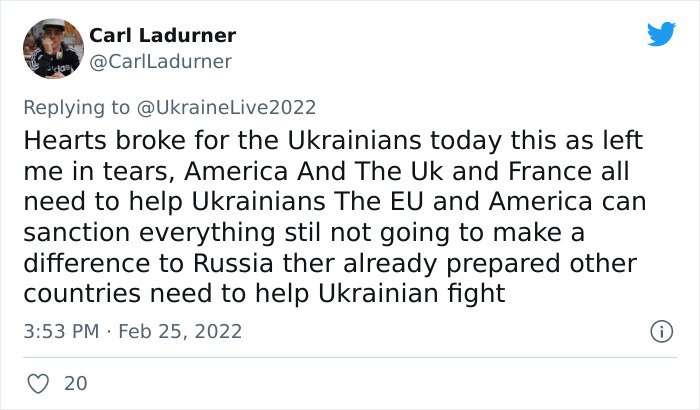

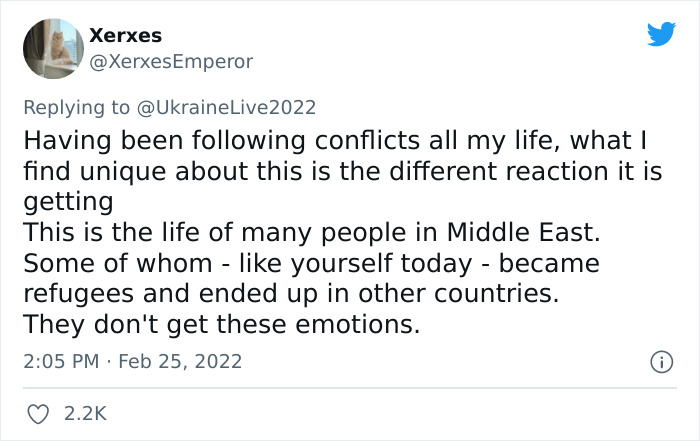

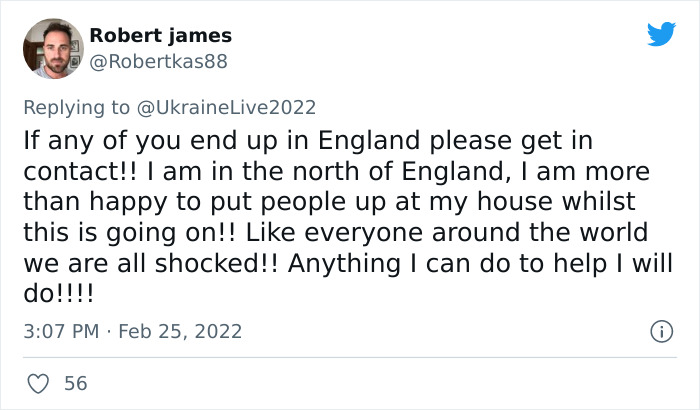

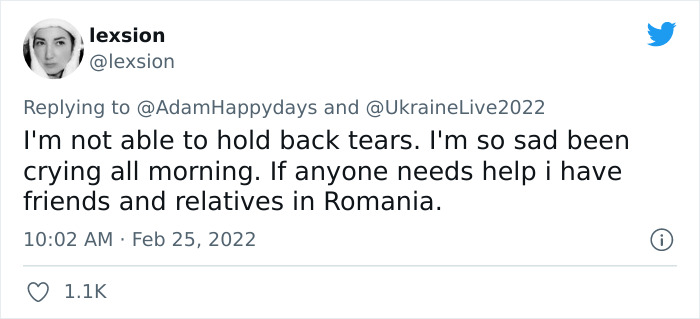

People from all over the world applauded the bravery of the young journalist and other refugees, and shared their support in the comments

Image credits: DesignNanette

Image credits: kary_cee

Image credits: KatBarclay2

Image credits: murray_nyc

Image credits: CarlLadurner

Image credits: ADHDemon

Image credits: XerxesEmperor

Image credits: Robertkas88

Image credits: lexsion

Image credits: AdamHappydays

Image credits: AfakeyW

Image credits: OonaghB24

Image credits: BarbieQuinn5

Image credits: gentileschiele

Image credits: hobsondp

As of today, more than 453,000 refugees from Ukraine have reached the safety of Poland, which shares a 500-kilometer border with Ukraine besides the similarities in language and culture. Still, no one, including Manny, would suspect that the last stretch of this migration might be the most difficult one.

“The last few hours at the Ukrainian-Polish border were the worst. All the refugees stopped and conglomerated into this human ‘crush’ with thousands of people pushing up against one another, unable to move,” Manny revealed. He saw someone getting a heart attack, many getting sick and shoving each other just for that tiny ticket of freedom.

“They were only allowing 10 people through the exit every 20 minutes. And there were over 2000 people there with me. So every time those gates opened, there was this human terror and panic of people savagely trying to get out.” After 8 hours of being elbowed, pushed and almost trampled, Manny officially crossed the border on the 25th of February where he was greeted with warm tea and doughnuts.

Asked if this horrific first-hand experience of unfiltered warfare has diminished Manny’s aspiration of becoming a full-time war correspondent, he said this: “It did change my perspective. I did not expect things to look the way they did, neither I did expect the scale of human suffering to be as large as it was.” While he is still recovering from the shell shock, Manny confirmed that if the opportunity comes — he would like to make it into a full-time career one day as this helps to “bring the world’s focus on the humanitarian crisis that is happening” all across the world.

Serena Parekh, a professor of philosophy at Northeastern University and the author of the award-winning ‘No Refuge: Ethics and the Global Refugee Crisis’, believes that so far neighboring countries, most prominently Poland, have played a significant role in assisting refugees. “I was really impressed that there were preparations made for refugees to cross over the border and be received in Poland and Hungary with all the logistical support,” Parekh told Bored Panda.

She thinks that there was a “change in tone” of how asylum seekers are being viewed in countries like Poland. “Starting with the influx of Syrians during the 2015 European migrant crisis, or last year’s Belarus–European Union border crisis — that was quite a different way of preparing,” Parekh said. “It was more like, ‘How can we fortify our border? How can we keep these people out?'” She believes this is partly because the “war is closer to home” and the Ukrainian demographic, both religiously and culturally, is similar to nations that are taking them in.

“There’s this notion that these ‘other people’, like Syrians or Iraqis, are used to war. They’re used to fighting and sort of normalizes war and violence. Therefore oftentimes ignoring refugees from other non-white countries,” Parekh explained. These are in fact not some empty claims: according to a study done by the Centre for Research on Prejudice — a professional academic center at the University of Warsaw — as many as 69% of Poles do not want non-white people living in their country. “The reason they don’t is a complex one. It’s connected to history. It’s connected to culture. It’s connected to how much we feel is related to the conflict that’s happening,” she told. “But I hope that after this conflict, people realize that there is a common connection between people who are suffering.”

Although Parekh sees the current refugee crisis as being handled sufficiently, considering the increasing numbers of refugees, one of the fears she has is one Europe will likely see in the long run. “It’ll be interesting to see if this feeling of solidarity and sympathy continues to live with people. Traditionally refugees have been very easy to demonize, particularly by worrying populous governments who want to protect their citizens from refugees,” she said. “So it’s a matter of time if Europeans start to see Ukrainians as an ‘economic drain’. I’m hoping that won’t happen. But if there were any other crises – I would expect that to happen very quickly.”

Not liking this post. It definitely has an undertone - not against Putin or the aggression or the war itself, but against Ukraine, who's "yanking" her men from their families etc. It sounds like Russian propaganda to me ( Romanian here, I know the discourse ). .

This is reality that we living next to russia has to live with... we cant have big enough paid army so we have to rely on conscript, its either roll over and become part of russia or have every able bodied man fight for their countries freedom.

Load More Replies...i know that the thought of soldiers stopping cars and busses to conscript men sounds terrible but if they want to keep their nation they need to be willing to fight for it. they can't expect 'others' to do it for them. help them-yes. sad but true but the price of freedom is never easy. with bad knees & a fake hip, i would take up arms to defend my nation.

I've read that Ukranian men above 51 still received compulsary Soviet army training, so that's why they are conscripting even old men now. They need their experience. Can't imagine what it's like to be in your fifties and having to go to war though!

This reads like absolute nonsense. What rank is a "Commissar"? To be clear, it isn't a military rank, it's an operative of the Communist Party which hasn't governed the Ukraine in over 30 years. If the OP can't identify this very basic fact then I don't put much value on the rest of their testimony. Place this account next to 'In Congo's Shadow' by Louise Linton.

No war is cool or good.. This should be stopped very soon. Russian and Ukraine people should not endure this hardship..

'inconsolably happy'? Journalist, my ass. Surprised at conscription of men in wartime? What a naive ninny!

You might call him naive, but how does it make him a "ninny" for being glad to have escaped an active war zone!

Load More Replies...Conscription is a bad idea regardless of circumstances. Conscriptees do not make good soldiers. They are trying to make someone, who does not want to fight, fight for them. Ukraine and every other country is better off without them. Besides, conscription is slavery.

The alternative for Ukraine right now is to wave a white flag and hand Putin the keys to the country.

Load More Replies...I've heard that Asians and Africans are having an even harder time getting out so this man is lucky.

I'm from Poland. As far as we know, there are problems with Ukrainian borders because their systems are weak and highly vulnerable to cyber attacks, that's why everything is taking so long with checking them. Many of them are here already, having a safe shelter in our homes.

Load More Replies...The US requires young men to register for selective service - this from the SSS site : Registration is a way our government keeps a list of names of men from which to draw in case of a national emergency requiring rapid expansion of our Armed Forces. I imagine if the US was under attack, the same demands would be made.

Maybe Poland could also take in the African and Indian students too...not just the whities. Would be nice if they weren't racist.

I imagine my brothers tasking me to get our parents to safety, only to have WWII vet dad find something a master machinist could do, and our mom saying she and I could damned well fill putin cocktails if nothing else. Only way I'd get her to safety would have been evacuating children. This assumes we were all much younger.

Calling Bullsh*t on the claim that people 18-60 are being conscripted to fight for Ukraine. That tweet stinks of borscht & vodka.

seriously? i have seen bus loads of Ukrainians boarding buses from Prague to the border for exactly this.

Load More Replies...then your country would probably not exist as it does without them. conscription is for defence of the country that conscripts. it's 100% necessary to defend the Ukraine from invasion.

Load More Replies...Not liking this post. It definitely has an undertone - not against Putin or the aggression or the war itself, but against Ukraine, who's "yanking" her men from their families etc. It sounds like Russian propaganda to me ( Romanian here, I know the discourse ). .

This is reality that we living next to russia has to live with... we cant have big enough paid army so we have to rely on conscript, its either roll over and become part of russia or have every able bodied man fight for their countries freedom.

Load More Replies...i know that the thought of soldiers stopping cars and busses to conscript men sounds terrible but if they want to keep their nation they need to be willing to fight for it. they can't expect 'others' to do it for them. help them-yes. sad but true but the price of freedom is never easy. with bad knees & a fake hip, i would take up arms to defend my nation.

I've read that Ukranian men above 51 still received compulsary Soviet army training, so that's why they are conscripting even old men now. They need their experience. Can't imagine what it's like to be in your fifties and having to go to war though!

This reads like absolute nonsense. What rank is a "Commissar"? To be clear, it isn't a military rank, it's an operative of the Communist Party which hasn't governed the Ukraine in over 30 years. If the OP can't identify this very basic fact then I don't put much value on the rest of their testimony. Place this account next to 'In Congo's Shadow' by Louise Linton.

No war is cool or good.. This should be stopped very soon. Russian and Ukraine people should not endure this hardship..

'inconsolably happy'? Journalist, my ass. Surprised at conscription of men in wartime? What a naive ninny!

You might call him naive, but how does it make him a "ninny" for being glad to have escaped an active war zone!

Load More Replies...Conscription is a bad idea regardless of circumstances. Conscriptees do not make good soldiers. They are trying to make someone, who does not want to fight, fight for them. Ukraine and every other country is better off without them. Besides, conscription is slavery.

The alternative for Ukraine right now is to wave a white flag and hand Putin the keys to the country.

Load More Replies...I've heard that Asians and Africans are having an even harder time getting out so this man is lucky.

I'm from Poland. As far as we know, there are problems with Ukrainian borders because their systems are weak and highly vulnerable to cyber attacks, that's why everything is taking so long with checking them. Many of them are here already, having a safe shelter in our homes.

Load More Replies...The US requires young men to register for selective service - this from the SSS site : Registration is a way our government keeps a list of names of men from which to draw in case of a national emergency requiring rapid expansion of our Armed Forces. I imagine if the US was under attack, the same demands would be made.

Maybe Poland could also take in the African and Indian students too...not just the whities. Would be nice if they weren't racist.

I imagine my brothers tasking me to get our parents to safety, only to have WWII vet dad find something a master machinist could do, and our mom saying she and I could damned well fill putin cocktails if nothing else. Only way I'd get her to safety would have been evacuating children. This assumes we were all much younger.

Calling Bullsh*t on the claim that people 18-60 are being conscripted to fight for Ukraine. That tweet stinks of borscht & vodka.

seriously? i have seen bus loads of Ukrainians boarding buses from Prague to the border for exactly this.

Load More Replies...then your country would probably not exist as it does without them. conscription is for defence of the country that conscripts. it's 100% necessary to defend the Ukraine from invasion.

Load More Replies...

83

50