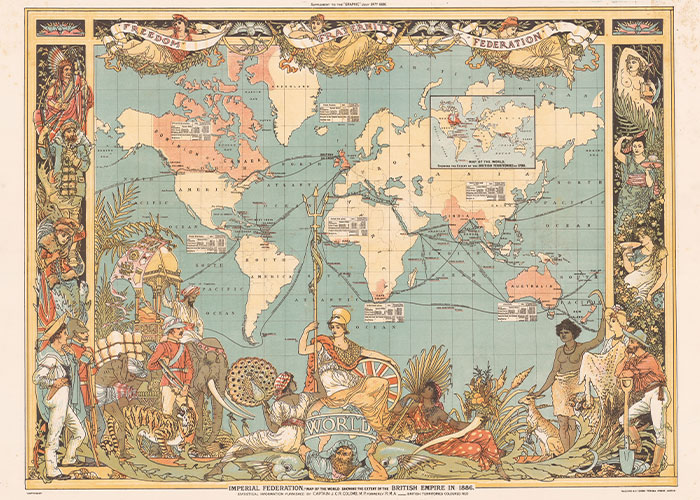

Horniman Museum To Return 72 Benin Artifacts To Nigeria, Brings Forth A Discussion On Object Repatriation

Considering our short duration on this Earth, anything of value that we can leave behind becomes a treasure and a learning opportunity for generations to come. A piece of history, if you will. Walking around museums, it’s hard not to be in awe of the stories objects tell, yet we must remember – most of history is written in blood.

How often do we consider the question – should these artifacts be here in the first place? I guess most of us think that nations came to a mutual understanding, sharing items with one another, or maybe they were just left at the museum’s doorstep, with a note reading ‘Please display me, here’s my story!’ It’s quite hard to come to terms with the fact that a majority of said items have been taken by force and blatantly stolen.

But some items are about to see their home again after over a century. The 72 objects, which were forcibly removed from the Kingdom of Benin during the British military incursion in February 1897, will be returned to the Nigerian government. Let’s get into the history, shall we?

More info: The Horniman Museum Press Release

The Horniman Museum and Gardens’ board of trustees has agreed to return 72 treasured artifacts to the Nigerian government

Image credits: HornimanMuseum

A London museum has agreed to return 72 treasured artifacts to the Nigerian government in what is being described as an “immensely significant” moment. The decision was made following a unanimous vote by the Horniman Museum and Gardens’ board of trustees.

Considering all of the objects were looted from the Kingdom of Benin (now the capital of Edo State in southern Nigeria) during the Benin Punitive Expedition in February 1897, they decided to transfer the ownership of the historic objects back to their place of origin.

“The collection includes 12 brass plaques, known publicly as Benin bronzes,” the press release by the Horniman Museum read. “Other objects include a brass cockerel altarpiece, ivory and brass ceremonial objects, brass bells, everyday items such as fans and baskets and a key ‘to the king’s palace.’”

The press release continued: “The Horniman received the request from [Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments] (NCMM) in January 2022 and has since undertaken detailed research of its objects from Benin to establish which are in the scope of the request.”

Consultations with community members and experts based in Nigeria and the UK ensued, with “all of their views on the future of the Benin objects considered, alongside the provenance of the objects.”

The items, including 12 Benin bronzes, belonged to the Kingdom of Benin, yet were stolen after the “punitive expedition” by the British in 1897

Image credits: Archie

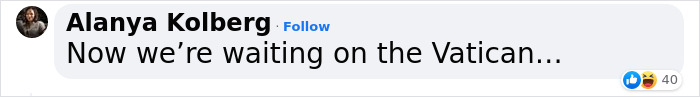

Eve Salomon, chair of the trustees of the Horniman Museum and Gardens, argued that there was clear evidence to suggest “that these objects were acquired through force, and external consultation supported our view that it is both moral and appropriate to return their ownership to Nigeria.” The museum will be working with the NCMM to assure longer-term care for the artifacts.

“We very much welcome this decision by the Trustees of the Horniman Museum and Gardens,” said Prof Abba Tijani, Director-General of NCMM. “Following the endorsement by the Charity Commission, we look forward to a productive discussion on loan agreements and collaborations between the National Commission for Museums and Monuments and the Horniman.”

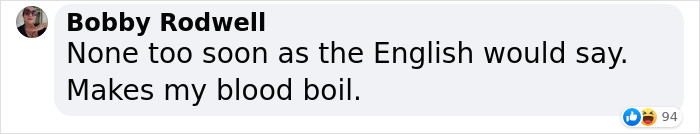

Let’s get into the history. According to the British Museum, the Benin bronzes “are a group of sculptures which include elaborately decorated cast plaques, commemorative heads, animal and human figures, items of royal regalia, and personal ornaments. They were created from at least the 16th century onwards in the West African Kingdom of Benin, by specialist guilds working for the royal court of the Oba (king) in Benin City.”

The Benin bronzes are the cast brass plaques which once decorated the Benin Royal Palace, providing an important historical record of the Kingdom of Benin

Image credits: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

Among the most well-known of the Benin bronzes are the cast brass plaques which once decorated the Benin Royal Palace and which provide an important historical record of the Kingdom of Benin. However, their acquisition was nothing short of tragic.

During the second half of the 19th century, a political and commercial movement, which later developed into the territorial land grab known as the ‘Scramble for Africa,’ saw industrialized European nations exert greater power across Africa. The desire to further extend British power and influence in the region led to a clash with the Kingdom of Benin in 1897, which began with what was named the ‘Benin Massacre‘ of January 1897.

The Kingdom of Benin had been coveted for its resources, which increased pressure for the territory’s incorporation into the British Empire. A trading treaty was agreed on by both parties, though Ovonramwen, Oba (king) of Benin, persisted in requiring customs duties, which was seen as an act of hostility.

Eve Salomon, chair of the trustees of the Horniman Museum, believed there was clear evidence to suggest “that these objects were acquired through force”

Image credits: Afshin Taylor Darian

Following price fixing, refusals by middlemen to pay the required tributes and hostilities in neighboring areas, the Oba of Benin ordered a termination of oil palm produce supply in 1896. To discuss trade and peace, James Phillips, an official in Britain’s Niger Coast Protectorate, led an unarmed trading expedition to Benin City in January 1897, demanding admission to the territory.

It was not a good time, as the Oba was celebrating Igue, during which the Oba is prohibited from being in the presence of any non-native person. To prevent the British from interfering with the annual royal rituals, some chiefs, acting against Oba Ovonramwen’s wishes, ordered that the expedition be attacked. Six British officials and almost 200 African porters were killed. Having heard of this, Britain responded immediately, mounting what they called a ‘punitive expedition’ to capture Benin.

An invasion force of about 1,200 soldiers were sent to what would become a “bloody and devastating” military occupation. Elspeth Huxley spent some time researching in Benin in 1954 and wrote: “It is a story that still has power to amaze and horrify, as well as to remind us that the British had motives for pushing into Africa other than the intention to exploit the natives and glorify themselves.”

“Here, for instance, are some extracts from the diary of a surgeon who took part in the expedition, ‘As we neared the city, sacrificed human beings were lying in the path and bush – even in the king’s compound the sight and stench of them was awful. Dead and mutilated bodies were everywhere – by God! May I never see such sights again!’”

About 10,000 objects were taken during the “bloody and devastating” military operation, now residing in 165 museums and many private collections worldwide

Image credits: Dennis Sylvester Hurd

Along with monuments and palaces, the Benin Royal Palace was burned and partly destroyed. Its shrines and associated compounds were looted by British forces, and thousands of objects of ceremonial and ritual value were taken to the UK as official ‘spoils of war’ or were distributed among members of the expedition according to their rank.

About 10,000 objects looted during the raid on Benin are held in 165 museums and many private collections across the world. Considering all this, museums have been refusing to return the Benin treasures, and as one curator put it: “We are not in the business of redressing historic wrongs.”

The Wall Street Journal noted that the British Museum, which holds around 900 Benin bronzes, has yet to commit itself to a similar action but is working with museum representatives from many European countries, as well as Nigerian officials and figures from the Benin Royal Palace, on a permanent solution. This talk of “research and cultural exchange initiatives” makes experts question how long that line can hold.

The British Museum, which holds around 900 Benin bronzes, has yet to commit itself to a similar action of repatriation, and the discussion continues

Image credits: Paul Hudson

Object repatriation and the wish to reclaim lost aspects of history and culture has been a topic of discussion for the past several decades. As explained by the Invicta Group, the fundamental argument for repatriating stolen artifacts is a moral one, with many people believing that historical items from other countries remain the property of those countries, regardless of who found them or who controlled that country at the time.

The other side of the coin shows a craving to preserve history, as in some cases, there is a legitimate question as to whether the repatriated artifacts would be safe in their new location. There are a number of instances of artifacts being poorly stored or maintained in museums which lack sufficient funding or expertise, as well as examples of items being damaged or stolen due to unrest.

Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) praised the decision, opening doors to collaboration in the future

Image credits: Son of Groucho

So what is the correct answer to this dilemma? I guess that’s something the future will show. The Horniman is now in discussions with NCMM about the process for the formal transfer of ownership and the possibility of retaining some objects on loan for display, research and education.

Perhaps loans and constantly changing artifacts will be the way museums operate in the future, but for now, looking at the 72 objects going back, we can’t help but think ‘you’ll be home soon.’

Very curious to hear your thoughts. Do you think museums/collectors have a right to keep and display objects obtained through theft and bloodshed, or should they give them back? Let us know your stance, and we shall see each other in the next one!

The “monumental decision” has stirred up a discussion online. Let us know your thoughts on the repatriation of objects!

If anyone is interested in reading a book on a period adjacent to this, read A Labyrinth of Kingdoms, by Steve Kemper. Follows a relatively unknown German-British explorer on the most unreal of trips. Incredible book and a fascinating look into Africa, pre-colonialism.

I have this book! It’s terrific and I highly recommend reading it

Load More Replies...Let’s not forget what the Taliban has done to priceless ancient artifacts and sites!

If anyone is interested in reading a book on a period adjacent to this, read A Labyrinth of Kingdoms, by Steve Kemper. Follows a relatively unknown German-British explorer on the most unreal of trips. Incredible book and a fascinating look into Africa, pre-colonialism.

I have this book! It’s terrific and I highly recommend reading it

Load More Replies...Let’s not forget what the Taliban has done to priceless ancient artifacts and sites!

94

21